Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Can Religion Be Empirical?

Can Religion Be Empirical?

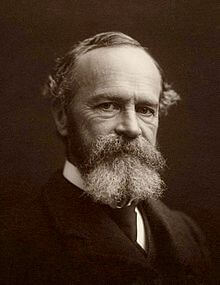

Let empiricism once become associated with religion, as hitherto, through some strange misunderstanding, it has been associated with irreligion, and I believe that a new era of religion as well as of philosophy will be ready to begin. — William James

Let empiricism once become associated with religion, as hitherto, through some strange misunderstanding, it has been associated with irreligion, and I believe that a new era of religion as well as of philosophy will be ready to begin. — William James

Empiricism is the theory that we get knowledge through experience. As James notes above, it’s usually associated with things like science, reason, skepticism, and irreligious attitudes. Religion is more often associated with faith (usually thought to be separate from reason), dogmatism, and Rationalism, the view that knowledge comes from reason rather than experience. Are these associations accurate?

James provides us with a useful name for the view that they are not: Radical Empiricism. He uses the term as a technical name for his own version of Pragmatism, but it’s still the best name for the theory I wish to propose: that we can get moral or religious knowledge from experience.

Let’s look at some examples and confront one of Radical Empiricism’s biggest challenges. For the moment, I’ll skip ethics and look directly at how this theory applies to various faiths.

Radical Empiricism in Buddhism

The Dalai Lama is one of those representatives of venerable religious traditions who treat those traditions as empirical.

In a speech on what Buddhism and neuroscience can do for each other, the Dalai Lama says that Buddhism has always recognized experience as a source of knowledge; indeed, it holds empiricism as the most important source of knowledge, overriding all others. As such, even the most important dogma from the most important religious authority of Buddhism can be corrected by experience!

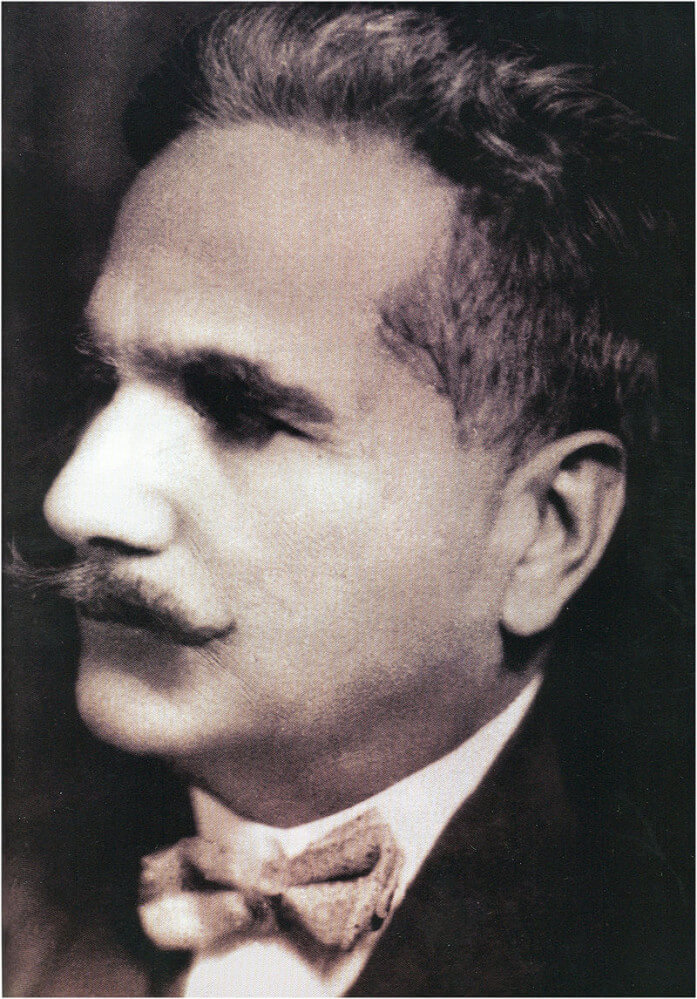

Radical Empiricism in Islam

Radical Empiricism in Islam

Representing Islam, Allama Iqbal emphasizes the empirical sources of religious belief and argues that religious belief can be a kind of empirical knowledge. (There’s an emphasis on Sufi mysticism, but he also talks about prophecy.) See my earlier post “What My Students Said About Religion and Science” for a better intro to Iqbal.

Radical Empiricism in Christianity

C. S. Lewis, presenting the basics of Christianity, refers to at least three empirical sources of knowledge of Christian theology. He talks about Christianity’s historical origins in the experiences of the Apostles of Jesus the Messiah, and about the experiences of the early church that aided in codifying the doctrine of the Trinity. He also talks about knowing God in experience through the life of the church.

C. S. Lewis, presenting the basics of Christianity, refers to at least three empirical sources of knowledge of Christian theology. He talks about Christianity’s historical origins in the experiences of the Apostles of Jesus the Messiah, and about the experiences of the early church that aided in codifying the doctrine of the Trinity. He also talks about knowing God in experience through the life of the church.

See my earlier post “Can Religious Knowledge Be Verified?” for a better overview of this theme in Lewis. (I’ve wondered if “Tested” might have been a better word than “Verified” in that title, but I’m coming around to the idea that I had it right the first time).

Empiricism and Dogmatism

The testimony of folks representing these three great religions undermines the notion that religion and empiricism can’t mix. But there’s more to that notion than the notion itself.

The real motivation behind this idea seems to be another idea: namely, that empiricism and dogmatic religion don’t mix well.

And that idea seems to be motivated by a third idea: that empiricism is always open to old conclusions being corrected by future experience.

That third idea is undoubtedly correct and it’s not a problem for anyone who lacks a dogmatic religion. It’s, therefore, no problem for the Dalai Lama, nor for — so far as I understand them — most forms of Buddhism, Confucianism, or Unitarianism.

It’s also no problem for William James, who said “[A]s empiricists we give up the doctrine of objective certitude” and consider all religious doctrines subject to correction by later experience. And yet, he defends the legitimacy of religious belief. Ditto for John Dewey in his book A Common Faith.

But can there be a religion which is dogmatic and empirical?

Let’s stipulate that this problem becomes more acute the more dogmas a religion has. According to the Dalai Lama, the problem’s not even there for Buddhism. But it is there for Islam, and it is a significant issue for Christianity having, as it does, quite a set of dogmas.

Regardless, I think empiricism and dogma can coexist within a religion, and that there are two ways we can get there:

1. Use the weaker use of the word “dogma.” Definitions 1, 2, and 4 from the dictionary would allow for a dogmatic empirical religion. A believer could say, “I accept the teachings of Islam/Sufism/Christianity/the Church/the Westminster Confession/the Baptist Faith and Message/Whatever. I am not certain they’re true, but I think they’re warranted by the empirical evidence. I suppose I could change my mind someday in light of new evidence.”

In this fashion, religious commitment can be entirely empirical, and significantly — though not entirely — dogmatic.

2. The leap. A believer might, under the third definition of dogma, conclude that his religion requires an absolute commitment to a given doctrine but simultaneously hold that the doctrine happens to be warranted by the evidence. He might conclude that the evidence warrants acceptance of the belief, but might also conclude that the nature of the belief requires an absolute commitment beyond that warranted by the evidence.

Someone holding this belief might analogize it to marriage: “Miss S. R. is the woman who should be my wife” about 93% probable, enough to believe it’s true. But Miss S. R. might require a total commitment and a whole ring, not 93% of a ring and 93% of a commitment.

In this fashion, religious commitment can be entirely dogmatic, and significantly — though, again, not entirely empirical.

(This is one of the weaknesses in James’ philosophy of religion. The case he makes for the permissibility of religious belief might apply to religious commitments that are strongly dogmatic, and thus are inconsistent with the systematically non-dogmatic religion he supports.)

“Let Us Hear the Conclusion of the Whole Matter”

So, I think not only that empirical religion is possible, but also that dogmatic empirical religion is possible (albeit more difficult).

It is actually impossible to be dogmatic (in the strong sense) and empirical with respect to the same belief at the same time. You can’t have absolute empiricism and absolute dogmatism.

But it is possible to have a worldview, or a life, or a system of belief that has a large empirical component or a significant empirical aspect as well as a significant dogmatic aspect.

Published in Religion & Philosophy

When you say “empirical confirmation” here, you mean sense-based and scientific, right? If so, you’re correct that there’s no empirical evidence for the supernatural events in the Bible.

But there’s no empirical evidence for most of the historical claims, either–or for the death of Socrates by hemlock or most other things we know from history.

The big point is that we can still know all of these things.

A smaller point is that we can know them from experience, even if it’s not our own, even if it’s not testable by scientific methods, even if the experiences are not always sense-based.

This question presumes a definition of “faith” as something not relying on proof. That might be an accurate enough definition of faith. So Aquinas, for example, giving proofs for God’s existence, has faith in dozens of other propositions that do not admit of proof.

Furthermore, the definition of faith does not exclude knowledge, justification, warrant, evidence, or reason. So one can give evidence without giving evidence that is, strictly speaking, proof.