Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Yesterday’s Non-Originalism

Yesterday’s Non-Originalism

Conservatives tend to be originalists in constitutional interpretation. But not all to the right of center are originalists, and not all non-originalists are hard-core, leftist living constitutionalists. There’s a view of non-originalism that’s remarkably compatible with conservativism. I don’t endorse it myself, but it’s well worth looking at.

Conservatives tend to be originalists in constitutional interpretation. But not all to the right of center are originalists, and not all non-originalists are hard-core, leftist living constitutionalists. There’s a view of non-originalism that’s remarkably compatible with conservativism. I don’t endorse it myself, but it’s well worth looking at.

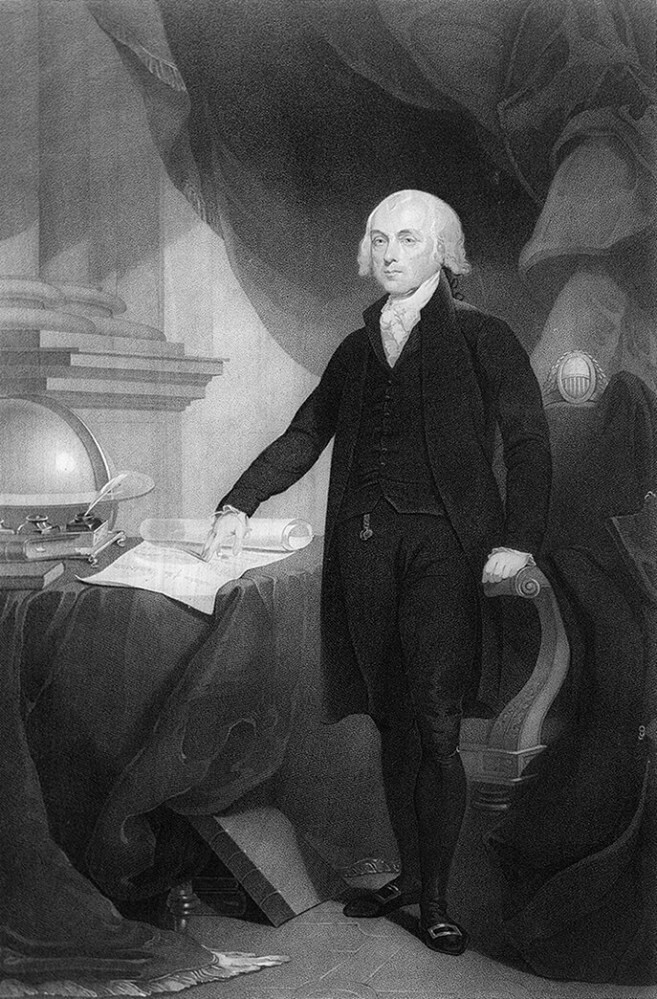

Another way of putting it: There’s an alternative to originalism that’s not today’s alternative. It’s not the Left’s. It’s old, or at least it has old roots. It has a lot to do with Madison. Let’s start with some of his principles and build up to that alternative:

First, Madison tells us that the Constitution is given its authority by the people:

[The Constitution] was nothing more than the draft of a plan, nothing but a dead letter, until life and validity were breathed into it by the voice of the people, speaking through the several State Conventions.

So said Representative Madison to the Congress in 1796.

Second, Madison tells us in that speech that the will of the people can determine the meaning of the Constitution.

Third, he tells us that the repeated interpretation of multiple branches of government sets a precedent of constitutional interpretation for future legislation. Madison:

. . . the constitutional authority of the Legislature to establish an incorporated bank . . . [is] precluded in my judgment by repeated recognitions under varied circumstances of the validity of such an institution in acts of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the Government, accompanied by indications, in different modes, of a concurrence of the general will of the nation . . . .

That was President Madison in his 1815 message accompanying a veto of the National Bank. He had once thought a National Bank unconstitutional, but here he’s changed his mind: Although he vetoes the bill, he makes it clear that he is doing so on policy grounds, not constitutional grounds. In 1816, he signed what he said was a better bill, authorizing the Second Bank.

Fourth, although he tells us that the meaning of the words does not change over time, he also tells us that the only legitimate meaning of the Constitution is that accepted and ratified by the people:

. . . I entirely concur in the propriety of resorting to the sense in which the Constitution was accepted and ratified by the nation. In that sense alone it is the legitimate Constitution. And if that be not the guide in expounding it, there can be no Security for a consistent and stable, more than for a faithful exercise of its powers. If the meaning of the text be sought in the changeable meaning of the words composing it, it is evident that the shape and attributes of the Government must partake of the changes to which the words and phrases of all living languages are constantly subject. What a metamorphosis would be produced in the code of law if all its ancient phraseology were to be taken in its modern sense. And that the language of our Constitution is already undergoing interpretations unknown to its founders, will I believe appear to all unbiassed Enquirers into the history of its origin and adoption.

That was Madison in a letter written in 1824.

Fifth, Madison tells us that the meaning of the Constitution chosen by the people through the repeated and continued decisions of diverse branches and levels of government overrules even his own view of the meaning of the Constitution:

My construction of the Constitution on this point is not changed. But I regarded the reiterated sanctions given to the power by the exercise of it, thro’ a long period of time, . . . under every administration preceding mine, with the general concurrence of the State authorities, and acquiescence of the people at large . . . all this I regarded as a construction put on the Constitution by the Nation, which having made it had the supreme right to declare its meaning . . . .

That was Madison in 1826, explaining to Lafayette why he had eventually opted not to veto the national bank.

Sixth, Madison again tells us that in his judgment, the people had determined the meaning of the Constitution. They had done so by “a course of precedents” set by all the branches of government and “amounting to the requisite evidence of the national judgment and intention.” And that, he tells us, is why he had not vetoed the national bank. (This is in an 1831 letter commenting on Jackson’s veto of the bank.)

So the people of the United States of America control the meaning of the Constitution, and they decide what it means through the repeated decisions of multiple branches of government. If these Madisonian principles are taken to their extreme, it’s pretty clear that the people can thereby change the meaning of the Constitution. Thus law scholar Gerard Magliocca says of Madison’s hermeneutics that “This Burkean approach to constitutional interpretation is the antithesis of originalism.” (page 217)

Now, Madison doesn’t actually say as much (as far as I can tell). These principles might not be taken to their extreme; they might accompany an originalism and simply be used only to clear up ambiguities in original meaning. Magliocca is countered by Judge Richard Arnold, who says of Madison that “He certainly was an advocate for originalism … in the sense of the original meaning of the document, when viewed against the times in which it was adopted.” (page 292)

But whatever. Let’s consider those principles taken to their extreme: The will of the people controls the meaning of the Constitution, and it is expressed through the decisions of the government the people select. Precedent determines the meaning of the Constitution. Precedent includes judicial rulings, but also executive decisions and, most importantly, acts of Congress. The people’s control over constitutional meaning is absolute. What a passage of the Constitution did not mean when it was written and adopted, it may mean today — if the people want it to.

So, for example, say an interstate highway system under federal management or federal funding is not consistent with the original meaning of the original Constitution or any subsequent amendments. No problem: It’s constitutional now. Ditto for a federally managed social security system.

And note how different this is from the left’s non-originalism:

- Judicial acts aren’t enough to change the Constitution. The Madisonian view requires the consent of the people via repeated decisions by multiple branches of government, as well as the States.

- Change in constitutional meaning happens slowly.

- One who discerns a change in constitutional meaning is looking to the settled will of the nation in the past. In allowing that change, he’s still conservative in an important sense — recognizing a change in the Constitution in order to not change the country that was created by We The People.

Now, I’m an originalist myself. But I think this here is a pretty respectable view. Though there’s a dispute between originalism and the Madisonian version of non-originalism, both are opposed to the Left’s “living constitution” version of non-originalism. In fact, while I could be wrong about this, I think when we talk about pitting originalism against this Madisonian view, we’re more or less talking about Ricochet’s Yoo v. Ricochet’s Epstein. And those dudes are both pretty cool.

Published in General

While I disagree with your comment #53, I’m with you here. I support the current approach towards Originalism not because it’s true (which I find an odd concept as applied here) but because I think it is the best approach towards interpretation (whether or not it gives specific results I like). Without some approach linked to the language we are adrift in the world of constitutional theory expressed in Justice Breyer’s book, Active Liberty, which is unmoored to anything textual and is essentially whatever Breyer thinks should be constitutional on any particular day. Breyer is essentially a super-legislator.

As the Dude said to Jesus Quintana, “yeah, well that’s just like your opinion, man“. I’d say, “yeah, I agree it is just my opinion“.

Then the deeper problem is, once again, your skepticism.

Well, there’s one counterexample to my claim. So it wasn’t true as a universal claim. It may yet be a reliable generalization. I, for one, accept Originalism because I think it’s true–though I also quite like the results! I think Thomas and Scalia are in the same boat. I know Gary Lawson and Michael Paulsen are in the same boat. If Yoo and Delahunty aren’t, their argument for its truth would be strange indeed.

Well, that may be so. I certainly didn’t intend comments #50 – #52 to present a comprehensive theory of constitutional interpretation. That would take longer than 750 words!

Still, while my remarks don’t constitute a complete theory, I believe they are correct as far as they go. How far that is is another question.

Well, my view is that both the text and the context are necessary to interpret a text. The context includes all the understanding of the term ‘freedom of speech’ inherited from English law. But let’s just say, ad argumentum, that you are correct and that we still can’t determine, even using context, whether the statute is constitutional. In this case there are no grounds for overturning it. This, of course, doesn’t help a congressman much, but he can employ prudential considerations as well.

I don’t see how this is so. The absence of some concrete circumstance would be a problem only for a particularly naive theory of original intent, but not for one that comprehends context and meaning. As I mentioned in an earlier comment, the MSM accused Bork of that sort of over-simplification, but it was a straw man. Bork didn’t have any trouble applying the 4th Amendment, for example, to new technology.

Words are abstractions and they can comprise concrete instances beyond the original set of instances from which the abstractions were drawn. The word ‘beetle’ applies even to species that have never been categorized. The existence of new circumstances really isn’t a problem for originalism at all.

The problem is often that in cases where the Constitution offers no text at all on a question the Court nevertheless overrules the States or Congress and declares something unconstitutional with no textual grounds at all.

Originalism has nothing to do with reading anyone’s unexpressed thoughts. Only the intentions expressed in the text count. See my comments #50 to #52.

I’m with Mark. Originalism is normative not descriptive. If it’s true, is it an empriical thuth that one can measure or test scientifically? A mathmatical truth one can prove by theorm? No. It’s ethically right.

It isn’t normative at all. It’s just a claim about what the meaning of the text is. The normativity comes from elsewhere: from the fact that this particular text is law.

What? What text is originalism a claim about? And what is that claim?

No. Originalism isn’t a claim about a text, it is the method by which claims about texts are resolved.

And no, the moral force of originalism doesn’t come from the fact that the topic of this particular post is the Constitution. The principles of originalism apply to any text whatsoever, to just that extent to which the text can be said to convey a message. (A poem or a song has purely aesthetic aspects which are not subject to originalism, but even here, to whatever extent a work of art can be said to convey a message, that message is conveyed by virtue of the application of originalist principles.)

Blender instruction manuals, Christmas cards, subway maps — they should all be interpreted to find their original meanings.

I agree, but I would add that the text they ignore the most are the 9th and 10th amendments.

One can claim it universally, as you do, which is nice. I’ve only been talking about Constitutional Originalism, a claim about the meaning of the Constitution.

Yes it is. It’s the claim that that meaning of the text is its original meaning–that the meaning doesn’t change except when the words change–that every change in meaning is the result of a change in words.

No, it underlies a method by which claims are meaning are evaluated.

Whence else comes it? Is there any moral aspect of the theory that the meaning of Hats Off to You, Charlie Brown today is the meaning it had when it was first published?

OK, then what would be the argument for it? I think you fail to appreciate the full force of the case for originalism. Orginialism isn’t some idosyncratic legal doctrine favored by conservatives for the partisan reason that it tends to promote their preferred policy outcomes. Originalism is partly constitutive of the meaning of meaning itself.

I have a mild objection to the term ‘originalism’ because it seems to me that having a label for it ought to be superfluous. Originalism really just boils down to the idea that one should make a good faith attempt to interpret a text. To give that idea a name seems to imply that originalism is just one example of several legitimate schools of thought on the subject. But anti-originalist doctrines (as opposed to ones that merely supplement it) are intellectually dishonest. To say that the meaning of a text has changed is just to lie about it. The meaning of a text just is the message that was intended to be conveyed in its original context.

You call it skepticism. I call it epistemic humility. More than once you and I have clashed over what I see as your propensity to proclaim an opinion as being “true,” and you have brought up that word again in this thread. I don’t see any sense in which originalism can be called “true.” It is simply useful. And its use is to influence judges not to write their own predilictions into the Constitution. I judge originalism by how well it carries out that purpose. And my answer is, it works well enough sometimes but offers little guidance in other cases. Standing alone, it is not enough.

To get back to the OP for a bit. I don’t think Madison’s position needs to be described as “non-originalism.” To see this, consider the three following questions one might ask about a constitutional controversy.

Originalism is an answer to the first question. I think Madison was following originalism in his interpretation of the Constitution. He believed the text did not allow a national bank. The reason he declined to veto the bill creating such a bank was Madison’s answer to the third question. Madison believed that other branches of government shared authoritative roles to play in interpreting the Constitution.

Madison wasn’t so much a non-originalist as a non-judicial-supremacist. Contrast Madison with G.W. Bush who signed a campaign finance law he believed to be partly unconstitutional, saying that we would see what the Supreme Court would do. Madison was deferential to Congress, Bush to SCOTUS.

I concur. He just has certain principles which, if taken to an extreme (as he did not) and in the absence of sensible Originalist principles (which he had), amount to a non-Originalism.

AWESOME. Beautifully put!

You have so much Pragmatism in you that I can’t help liking this comment!

Probably the only other thing to say is that you really have no idea what epistemic humility really is. You take skeptical positions and call it epistemic humility; it’s really epistemic servility with a tinge of epistemic arrogance. True epistemic humility requires (at times) bowing the mind to reality, calling it known, and calling our ideas about it true.

What would be an argument for Constitutional Originalism that doesn’t apply texts generally? Michael Paulsen makes one “Does the Constitution Prescribe Rules for Its Own Interpretation?” Delahunty and Ricochet’s Yoo make another one in “Saving Originalism.”

Naturally. It’s a true and eminently rational and justified theory. My little mind has barely begun to understand it!

Whoever said it was? Not I.

I offer no objection to this.

Awesome.

Thanks for the links, they look interesting. I read the summaries, although not the full articles, and if I were wiser, I’d wait to read and digest them before opining, but I’m not wiser…

The Michael Paulsen paper appears to be an argument that the text of the Constitution provides subtle clues showing that it should be interpreted using originalism. The Yoo article, according to Yoo’s summary, makes the case that the framers must have intended the Constitution to be interpreted using originalism based on the political context of the Constitutional Convention.

If my reading (of the summaries) is correct, then while both pieces may be of interest on their own grounds, neither can form the basis of an argument for originalism without begging the question. If one believes either that the Constitution’s text (in the case of the Paulsen paper) or the framers intent (in the case of Yoo’s article) are authoritative then arguments for originalism based on those pieces are unnecessary, as one already believes originalism on independent grounds. Alternatively, if one does not regard text and authorial intent as authoritative then the arguments based on the text and framers intent are unconvincing.

Ah, but the left says it — pretty much all the time. I think the strongest (and correct) response is to base Constitutional Originalism on a general theory of meaning and communication.

I think the best argument for Constitutional Originalism is that we don’t choose to be ruled by nine robed masters.

Beautiful! I think Paulsen concurs and elaborates beautifully. Yoo I don’t recall so clearly (though I have a vague idea that his and Delahunty’s argument may have been independent of authorial intent).

Oh, well I agree with that!

(I’m pretty sure Thomas does this. I dabbled in that approach myself in the comments on Yoo’s article. Paulsen may do the same somewhere or other, but I don’t recall. I also don’t recall if Lawson does anything like that in this fine little article, but he may.)

Hear, hear!

There’s a convenient Madisonian defense of Originalism that follows from this insight: We the People gave the Constitution its authority.

Thus the meaning of the Constitution is that known by We the People.

So the meaning of any part of the Constitution is that known by the (technically fictional) very well informed and very reasonable reader at the time of the adoption of that particular part of the Constitution.

If I remember rightly, Gary Lawson’s article here is a particularly good explanation of this version of Originalism. He’s one of the best of the best living Originalist scholars. It’s neat that he aligns so nicely with this theme from Madison, a founder and Constitutional author. (However, Mack the Mike might want to tweak a defense like this to rely more on authorial intent.)