Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Stalin, Heart Surgeons, and Ben Carson

Stalin, Heart Surgeons, and Ben Carson

So as you can imagine, my family has been having a lot of conversations lately about cardiology and cardiac surgery. My father was already quite well-informed about the subject, because his own father suffered from cardiac disease (confirming the well-established wisdom that such things run in the family, and making me think it might be wise one of these days to have my own ticker checked out: What keeps me from doing it is not wanting to know, which I know isn’t the most courageous way to approach these matters. I’ll get around to it. I think I’m okay for now.)

So as you can imagine, my family has been having a lot of conversations lately about cardiology and cardiac surgery. My father was already quite well-informed about the subject, because his own father suffered from cardiac disease (confirming the well-established wisdom that such things run in the family, and making me think it might be wise one of these days to have my own ticker checked out: What keeps me from doing it is not wanting to know, which I know isn’t the most courageous way to approach these matters. I’ll get around to it. I think I’m okay for now.)

Anyway, we’ve been talking about the personalities of people who go into cardiac surgery as a speciality. There are lots of stereotypes, of course: I liked this blog, written by a woman who in no way would I consult for any medical problem, given that she’s “a physician who is intuitive and a Reiki Master/Teacher discusses healing from ‘the front lines’ of the mind-body connection in the hospital setting.” But her description of the temperaments of cardiovascular surgeons seemed interesting to me:

Cardiovascular surgeons are the last of the “old boys school” for the most part. There are notable exceptions, which I will discuss later. They are emotional, angry titans who split sternums and work on some really sick people. Some contain it better than others. … I have seen patients die from pride of the surgeon and the anesthesiologist and the rest of the team. … Pride is an element in the heart room. Ego reigns. Dominance, aggression, control, continuity. There is no compassion. Not for anyone…

On this blog, Aaron Singh asks why surgeons have such big egos:

[The surgeons] were the ones who walked past you with a sense of purpose, with an expression that sent lesser medical personnel scurrying out of their paths in terror, and with eyes whose gaze could physically melt medical students if you weren’t careful. Several walked past us, instantly recognizable, and those who bothered to look at us did so with a disdainful expression, dismissing our existence as being too trivial to bother their exalted minds. They were Lords of their Domain; entire operating theatres were built as shrines to their greatness. Why shouldn’t they walk around as if they owned the place?

I’ve always wondered why surgeons seem to be more affected by the famous God complex that seems so prevalent in the medical profession. Recently, my cousin brother underwent surgery, as I talked about in my previous post, and the surgeon who operated on him, whilst perfectly competent, also demonstrated this uppity demeanour. She strode into the OT (fashionably late) without seeing him pre-op, and didn’t even check on him post-op. During the surgery she didn’t bother to reassure him; it was the nurses who did this.

Or take this quote from Frank C. Spencer, MD, FACS, Cardiothoracic Surgeon:

“Stepping into the operating room to perform heart surgery on a sick patient, being fully in control of the large team of people who are required to do the procedure, and feeling totally prepared to perform the task at hand is an unbelievable feeling that can barely be described.”

Or this one from Dr. Paul Corso:

Heart surgeons are aggressive, intelligent, driven people who have mental, emotional and physical endurance. We are born with all of these factors, but need to develop them into their highest form. Some people say heart surgeons are jerks, and we’re probably that, too.

“Cardiac surgeons,” writes Kathleen Doheny, “driven and dedicated, tend to see things in yes or no terms, says a physician in another specialty. ‘Fish or cut bait. They tend to be  pushy.’ When a cardiac surgeon decides it’s time to head to the operating room, stand back.”

pushy.’ When a cardiac surgeon decides it’s time to head to the operating room, stand back.”

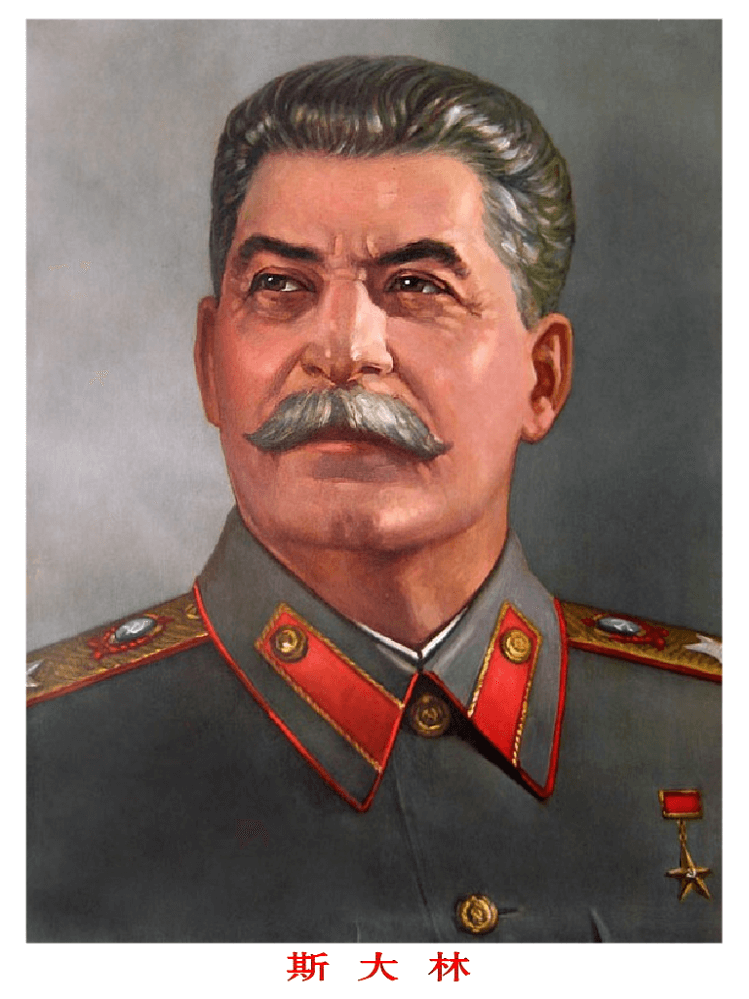

Anyway, this morning my brother and I were wondering how this personality type — and it is, it seems, a distinct one — would translate into a politician’s leadership style. We were playing a little game, trying to decide which figures from history would have been good cardiac surgeons. Perhaps Stalin missed his calling: Might he have been a fine cardiac surgeon instead of a bloody tyrant?

What about Ben Carson? I imagine that neurosurgeons and cardiac surgeons share  similar temperaments, as a rule. Is a neurosurgeon’s temperament the right temperament for the President of the United States?

similar temperaments, as a rule. Is a neurosurgeon’s temperament the right temperament for the President of the United States?

Are any of you cardiac surgeons? Neurosurgeons? Know any? Are the stereotypes true? Would knowing that surgeons share a personality type seem relevant to you in trying to figure out what kind of politician a surgeon might be? In Carson’s case, after all, knowing that he was a great surgeon is really all we know: So would that kind of personality be an asset in the White House or a liability?

(By the way, although I didn’t get to spend much time with him, my father’s surgeon seemed to defy these stereotypes: He’s a gentle and very devout Catholic who goes to Mass every morning, and seemed in no way a bully or a jerk. So obviously, there are exceptions.)

Published in General, Science & Technology

Quoting myself here to add an illustration of the point I was making:

Some years ago I read a letter to the editor from an anesthesiologist who had been called to the hospital for an emergency surgery on a cold, winter morning, perhaps 4am or so. He was pulled over and given a speeding ticket for going 40 in a 25 zone. The officer escorted him the rest of the way to the hospital, but still wrote out the ticket and the judge still found him guilty and made him pay the fine.

He wrote that the message he was receiving from the legal system was that they prefer that he drive the speed limit than get to the hospital in time to save a life, and that’s what he intends to do in future.

I’m with Mr Axe. It’s not bad faith to respond to the signals you’re being sent.

If I die during childbirth, I’m not gonna sue. (True, my husband and family might sue on my behalf, but they’d be suing on behalf of an adult who knowingly put herself at some risk by deciding to birth a baby.)

If I don’t die during childbirth, but my child is killed or maimed during the process, I’m in a much better position to sue. (And it’s only natural to resent the risks imposed on new, innocent life more than the risks an adult has freely consented to.)

I don’t know how strong the “dead moms don’t sue” effect is, but I’d be surprised if it were nothing.

It would be nice if doctors always chose evidence-based medicine over responding to the incentives they’re set. Nice, but not realistic.

Fortunately, women very seldom die from giving birth anymore. There is the odd woman that will go into DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation) which is serious bad news bears, but unlike when my mom was a high risk labor and delivery nurse, we are much much better at treating it.

Agreed. We’ve done so much to minimize the risk.

I’d still expect fewer lawsuits from dead moms than from live ones with a grievance.

He’s such a naive brain-washed child, isn’t he?

I think Charles Krauthammer calls his way of thinking adolescent.

The incentives aren’t nearly as simple as what you’re making them out to be. Doctors set the “standard of care”, and following the standard of care is a primary defense in a lawsuit. So yeah, the doctors could choose evidence-based medicine “over the incentives”, because they also set the incentives, by controlling the standard of care. Case in point:

ACOG is, of course, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. If coloring the medical literature to cover your butt in a lawsuit later on isn’t bad faith, I’m not quite sure what would qualify.

“Mere mortal physicians”? Good Heavens.

“My agenda”, for starters, is that I expect them to have a passing familiarity with medicine.

The underlying tone of these comments seems to be: oh, medicine is so hard, you can’t expect us to produce better outcomes.

Baloney.

If McDonalds can do it, so can a doctor. This sort of medical arrogance displayed in your comment is the reason why doctors get sued so often: they commit so much malpractice. The problem is not the legal system.

As both a physician and an attorney, I think the problem is both. And I suggest to you from 37 years of medical practice that my assertion was based in humility therefrom, not from arrogance. Medicine, to the extent that life-changing decisions are made in seconds, minutes or even hours, more resembles a battlefield than a courtroom. It does not lend itself to an idealized form of decision making protocol. Things are usually not that clear in the moment.

Notions of practicing evidence based medicine sound great, just like the generals’ battle plans and we all know the saying about battle plans. Many situations in medicine – like whether or not to do a c-section are not as clear cut in the moment as they may appear after lunch or a recess in a deliberative courtroom. I would further assert that the impulse to impose rigid checklists is the same ultimately totalitarian impulse which is driving us toward the promised progressive administrative utopia. How is that working out?

Lawyers will assert what they can. My experience suggests the corrupting influence of very large expert witness fees readily attract physicians who will testify to most anything. They are also a substantial part of the problem.

This.

People often discount the back and forth, the “push me, pull you” aspect of diagnosing and treating patients. It’s not at all clear cut and orderly, especially when there are multiple comorbities, and treating one issue will exacerbate another. Doctors and nurses are human, and will make mistakes, but we do our damnedest to make sure it happens as little as possible. And when big mistakes happen, and a patient is seriously injured or killed by the mistake, we take it more to heart than people could ever know. There was a nurse a few years ago who killed herself because she couldn’t live with the fact that she had made a medication calculation that contributed to the death of her patient.

Tuck, I promise you, by and large, we don’t take what we do casually.

And don’t forget the extent to which patients and their families are part of the problem. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen doctors end up doing something that patients want, because the patient “wants something done.” I’ve seen this right up to the point of a patient flying to Germany for a ridiculous, pointless procedure. If it’s a surgery, the doctor can theoretically refuse, although sometimes they just don’t. If it’s something like an intubation at the end of life, that’s really hard to refuse.

Of course not as simple as I made them out to be – I was deliberately simplifying to raise a question.

Even so, why would the “standard of care” that doctors set for themselves to create immunity from suit be totally immune from outside pressure?

I don’t see why the practice of medicine would ever be entirely dedicated to precisely administering scientifically-correct medical care rather than giving the people doctors answer to (whether it’s patients, administrators, or government overlords) what they demand. I would naturally expect doctors (and nurses, and anyone else involved in caring for the eccentric creatures known as homo sapiens sapiens) to sometimes find it easier to give into demands that aren’t evidence-based, just to get on with the rest of life.

Note that there is no such thing as THE standard of care. It encompasses a “reasonable standard of care”, including what is done by a minority of practitioners. It is not majority rule, though the practice of a majority may carry more weight in the eyes of a jury.

Evidence based medicine and checklists have much to contribute in primary care and some specific applications in specialty care. For example, what screening tests are performed under various circumstances and at what age statistically improve outcomes in large populations. On occasion, however, deviating from guidelines may be very beneficial for a given patient and eliminating physicians’ ability to do so will harm individual patients (deviation may also harm some, but I believe more will be helped than harmed based on clinical judgment – the “art” of medicine).

In anesthesia, we use checklists to prepare our equipment – extensive ones at the beginning of the day, more abbreviated ones between cases. Aviation studies of human factors contributing to error have taught anesthesiologists sufficiently well how to design equipment with alarms and how to establish process (to reduce distraction) that anesthesia is about 80 times safer today than it was when I started in 1978. Anesthesia was cited by the Institute of Medicine as the specialty which has made the greatest progress in patient safety. Our understanding is that well-trained humans have a low, but irreducibly low error rate and we must design equipment and process which will protect patients from some inevitable errors.

FYI, the Army Commander’s Battle Staff Handbook [PDF]. It’s full of checklists.

As my previous link made clear, it’s working out quite well in medicine, and in every other field where quality of process and output is a priority. The medical literature is full of examples. It’s hardly a new idea, as it dates back to the 1950s.

As far as your silly claim that it’s part of the “promised progressive administrative utopia”, noted Progressive “President Ronald Reagan awarded [the popularizer of this approach] the National Medal of Technology in 1987.”

It’s a defense in a legal case. If a patient claims malpractice, and the doctor shows that he was following the standard of care, that’s a very strong defense.

Standards of care can change, and they’re controlled by the doctors themselves.

I expect that if this approach was taken, there would be a lot less medicine practiced, but the results would generally be better.

That approach is exactly what has led us to the current problem of over-prescription of antibiotics and the rise of resistant bacteria. This will have real consequences, and already does.

“U.S. Medicine Has Entered the Post-Antibiotic World”

Be that as it may, what really counts from the patient’s perspective is the outcome, not how the practitioner feels about it. The patient has to live with the outcome, the practitioner does not.

The value of a standard or a checklist is not so much in having one as in making it have the right elements. The problem we face in medicine is that checklists tend to be designed in Washington, DC, by people who have no idea what it is that they’re doing, in cooperation with lobbyists paid by insurance companies and by physicians’ groups. So they tend to be silly at best and time-consuming and counterproductive at worst.

Take, for example, the standard of providing patients with a “clinical summary.” Sometimes this is a reasonable thing, but more often than not it is a pointless waste of energy and resources.

Sorry. Duplicate post.

That’s not only not good reasoning, but it’s demonstrably not true. Many common surgical procedures have been shown to be ineffective once they are tested.

“U.S. Coronary Stent Market in Decline due to Over-Stenting Procedures”

After stents were shown to be ineffective in one of the commonly-used scenarios, many doctors continued to use them, nevertheless. Stents were incredibly lucrative for the doctor, and inserting a stent was a relatively low-risk procedure. The lure proved too attractive for far too many doctors.

That was a $110 billion market. It’s unknown, of course, how many of those procedures should never have been performed.

Yes, much of what is done in medicine is unhelpful and some harmful. Nonetheless, anger and name calling don’t often persuade. Also, I believe a broad experience in the front lines of a large endeavor like medicine gives a different perspective than that which results from a biased sample of bad practice or merely bad outcomes resulting from decent care – say the perspective of a personal injury lawyer. The ones I know have quite an animus toward physicians. Happily for me I suffer no such feelings toward them.

LOL. I’ll buy that.

But when well-designed they clearly offer real, measureable benefits.

I can only imagine.

I get that. I have no problem understanding the role of “standard of care” in malpractice cases. But as Lucy said, no matter how much good a proper, scientific standard of care could do, I wouldn’t find it surprising for the standards of care actually used to deviate somewhat (or even a lot, depending on political pressures) from that ideal. Lucy mentioned lobbyists and bureaucrats. And as I mentioned,

I agree with you about antibiotic overuse.

As a patient, I do try to educate my expectations according to evidence-based research. I grew up with the expectation, for example, that every sinus infection “needed” antibiotics, but successfully changed my mind.

In reference to the much-publicicized ineffectiveness of procedures, it may be that more than established facts are at work. For years, media publicized the latest and greatest advances of medicine, almost to the point of cheerleading. Of course, this was welcomed by all elements of the medical establishment. It created un-skeptical demand. It enhanced the incipient urge to “do something” to fix every problem. This is a great bias both in medicine and in society at large. We are often discussing here the consequences of the political consequences of this impulse.

Beginning around 2000, a remarkable reversal of the polarity occurred and reports began to surface about the risks and ineffectiveness of many medical and surgical treatments. They now appear regularly. It is very likely there is truth in some of these reports and, in my view, it is equally likely the pendulum has swung too far in the direction of overstatement. It is politically convenient in a climate of over-utilization and ever-increasing healthcare costs. Just as researchers who find more evidence of global warming are assured more government grants, I suspect those who find ineffectiveness of medical treatments are politically favored (government is “doing something”). The truth is probably somewhere in the middle.

Just as truth is often a casualty of the “adversarial truth-finding” process in courtrooms, it may also be a casualty in the politicization of scientific investigation of medical effectiveness. It was in the past, only in the opposite direction.

You don’t have to imagine. To civil westman’s argument that these aren’t useful in battle or in crises:

As Westman knows, we use a lot of checklists in the OR (anesthesia, time outs, counts before closing) in an attempt to avoid wrong site procedures and such. The counts are very helpful I’ve found (well, for the most part), but the time out process is largely for show. You can ramble through a time out without really paying attention. The thing that does decrease wrong site errors- being well rested (says the first assist who did a 10 hour microvascular case on three hours of sleep, and not because I was partying or anything). That’s why there’s been such a pushback against the crazy hours that residents were logging in the past.

LOL. That’s a whole ‘nother topic. If you were trying to increase the rate of medical errors, there would be few more effective policies to introduce than sleep-deprived people.

I have not suggested that checklists are not useful and improve outcomes in some circumstances. I was specifically addressing their place in the decision as to whether or not to perform a C-section. My impression is that there are numerous factors at play in taking the decision and many of them are not binary, rather multiple factors which are not yes/no and which are subjective.

The attempt to systematize medical decision making is commendable, just as is the making of public policy. It is apparent to most of us here that the latter has many limitations and untoward consequences. When I speak of the utopian impulse in society at large or in medicine in particular, I mean the unwillingness to accept the limitations of regimentation. For the foreseeable future, some place remains for individualized decision making both for how we interact in society and how physicians and patients collaborate to decide about care. Medicine by algorithm has a place, but also has limitations. Not everything can be perfected through preordained standards, guidelines and checklists.