Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Pain Demands An Explanation

Pain Demands An Explanation

There are two truths about pain that every good conservative believes. First, pain is the most straightforward incentive; people need pain to correct their behavior. Second, we believe in “no pain, no gain;” i.e., that pain is a necessary sacrifice in the pursuit of accomplishment. In either case, pain is useful. At least, that is our moral ideal of pain and how it ought to act to fulfill its purpose.

There are two truths about pain that every good conservative believes. First, pain is the most straightforward incentive; people need pain to correct their behavior. Second, we believe in “no pain, no gain;” i.e., that pain is a necessary sacrifice in the pursuit of accomplishment. In either case, pain is useful. At least, that is our moral ideal of pain and how it ought to act to fulfill its purpose.

That pain, whether of the body or the psyche, serves a useful purpose is easy enough to see. We need only consider what happens when it’s absent. Lepers and CIPA patients become horribly disfigured because they can’t feel pain. Lepers lose sensation in their extremities. CIPA patients cannot feel pain at all. They only avoid injury and disfigurement through a tedious process of consciously checking themselves, which is much less effective than simply feeling pain. Similarly, mania and psychopathy both reduce a person’s capacity to feel the psychic pains — shame, remorse, etc. — that keep us on the straight and narrow, and both mental states are quite sensibly regarded as dangerous.

That not all pain serves a purpose is somewhat harder to see. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome and phantom limb pain both loudly contradict the notion that pain is always useful, but both are so freakishly rare they can be dismissed as aberrations. While much more common, garden-variety chronic pain is so frustratingly subjective that it’s tempting to moralize it away as a manifestation of moral fragility, as a “cross” bestowed on us by a loving God for the purpose of spiritual refinement, as a failure of mind over matter.

But pain demands an explanation, and pain without any apparent meaning is an affront to us. It shouldn’t exist. As the founder of painscience.com puts it:

Pain is a message, a sort of public service announcement from your brain about a credible threat. Supposedly.

In the case of the pain of a burn, the message is simple: “Fire is super-duper dangerous! Don’t mess with it!” But does the message really need to be as loud as it is? Does it have to last for days?

Maybe it does. I always assumed that the explanation for this was that pain has to be extreme to have the desired effect — that the logic of neurology and psychology requires pain to actually be emotionally traumatic in order to ensure that we remain permanently keen to avoid whatever caused it. This rationalization of the severity of pain can be stretched to include basically any kind of pain that has any kind of obvious cause.

But what about pain with no apparent cause? Just what is it that your body is telling you to stay away from when you have an unending case of low back pain or plantar fasciitis? What’s the “information” encoded in that pain?

“Never sleep comfortably again?”

“Never walk again?”

And why does it continue telling you? Permanently, in some cases.

…[W]hen the message of pain is actually debilitating for long periods, how exactly is that sensation helping?

Descartes popularized the idea that pain is a mechanical signal sent to the brain, incentivizing action, rather analogous to the price signal of economic theory. But there’s evidently a lot of noise in that signal. How do we explain pain that doesn’t seem to accurately correspond to incoming noxious signals?

One way would be to divide apparent pain into two parts, labeling pain that corresponds to an incoming signal like tissue damage “real” or “true” pain, while pain that doesn’t correspond to an incoming signal is dismissed as noise, as our perception playing tricks on us. There’s much to be said for this signal-versus-noise model of pain. It accounts for both the usefulness of pain (the signal) and the variable perception of pain (the noise). It also suggests that correcting our perceptive defects can diminish “false” or “unnecessary” pain (reduce the noise in our pain-signals) just as common experience, philosophy, and religion have taught us all along.

But it’s not the whole story. Pain is better modeled as the brain’s way of alerting itself to an implicit threat. The “noise” our brains add to the incoming noxious signal to produce perceived pain isn’t just noise, but itself contains signals and added information. The subjective nature of pain is then not a bug, but a feature; the result of a brain that uses other cues to put incoming noxious signals into context, in order to form a more complete picture of what’s happening to us. Pain doesn’t emerge until the brain interprets multiple cues and decides a threat exists, a threat worth screaming to itself about.

Pain is an opinion on the organism’s state of health rather than a mere reflective response to an injury. There is no direct hotline from pain receptors to ‘pain centers’ in the brain. There is so much interaction between different brain centers, like those concerned with vision and touch, that even the mere visual appearance of an opening fist can actually feed all the way back into the patient’s motor and touch pathways, allowing him to feel the fist opening, thereby killing an illusory pain in a nonexistent hand.

That “real” pain isn’t just a raw signal, but an explicit (and attention-hijacking) manifestation of the “implicit perception of threat” our brains synthesize from multiple cues is dubbed the “neuromatrix theory” of pain. The brain’s ability to amp up or damp down pain according to what it thinks the pain means isn’t just a perceptual quirk that can be consciously hacked to overcome pain, but instead exists for a reason – and is, alas, not entirely under our conscious control:

“Pain really is in the mind, but not in the way you think.”…

…[T]he brain can’t be manipulated simply by wishing, force of will, or a carefully cultivated good attitude. The brain powerfully and imperfectly controls how we experience potentially threatening stimuli, but I’m sorry to report that you do not control your brain. Consciousness and “mind” are by-products of brain function and physiological state … It’s not your opinion of sensory signals that counts, it’s what your brain thinks of it — and that happens quite independently of consciousness and self-awareness. Many wise, calm, confident optimists still have chronic pain.

… Your brain modifies pain experience based on a number of other things that are completely out of your control, or rather difficult to control, or even just impractical to control. For instance, if you view a painful hand through a magnifying glass, it will actually get more swollen and inflamed — that is, if you make it look bigger, it will get bigger. And the reverse is true! Use optics to make it look smaller, and swelling will go down. [See this study. But also see this study, which found an inverse relationship!] Incredible, right? Jedi pain tricks! But … do you have a de-magnifying glass handy?

… Although it is technically the brain’s prerogative to ignore painful signals from your tissues, that doesn’t mean that it will — if there is a destructive disease process going on, for instance, the brain will usually not ignore those signals! The pain system evolved to report problems, and it will diligently do so.

…The brain has a picture how things should be, and acts accordingly… even when it’s blatantly ineffective… [I]f the brain believes there’s a threat, you’re going to hurt, no matter how pointless it is or how intensely you focus on trying to have more reasonable and rational sensations.

But that doesn’t mean that we’re powerless. Mind has some influence over brain.

The bad news, then, is that pain is neither a straightforward incoming signal nor one directly influenced by conscious control. The particularly bad news for chronic pain sufferers is that that the longer pain persists, the weaker the relationship between pain and damage in the “hurting” tissues becomes. Not only do “the neurons that transmit nociceptive input to the brain [and] … the networks of neurons within the brain that evoke pain become sensitised as pain persists,” but “the proprioceptive representation of the painful body part in primary sensory cortex changes,” too. Chronic pain remodels perception in self-perpetuating ways.

The good news, though, is that pain can be indirectly influenced by conscious decisions, including attitudinal changes and lifestyle adjustments; just not always in “obvious” ways.

For example, mood obviously influences pain (and pain influences mood), but getting the evidence to agree with one simple pet theory is hard:

Experiments that manipulate the psychological context of a noxious stimulus often demonstrate clear effects on pain, although the direction of these effects is not always consistent … Despite the wealth of data, consensus is lacking: some data suggest that attending to pain amplifies it and attending away from pain nullifies it, but others suggest the opposite.

Anxiety also seems to have variable effects on pain. Some reports link increased anxiety to increased pain… but other reports suggest no effect …

Expectation also seems to have variable effects on pain. As a general rule, expectation of a noxious stimulus increases pain if the cue signals a more intense or more damaging stimulus and decreases pain if the cue signals a less intense or less damaging stimulus … Further, cues that signal an impending decrease in pain, for example the process of taking an analgesic, usually decrease pain. Thus, expectation is thought to play a major role in placebo analgesia.

To make matters worse, just as increased inflammation causes pain “directly” in the part affected, increased inflammation also causes generalized “sickness behavior,” including depressed mood, which itself increases sensitivity to pain. The relationship between pain, tissue states such as inflammation, and mood seems quite complex, with causality running in every direction. For example, patients treated with inflammation-producing drugs such as interferon often become depressed. Conversely, COX-2 inhibitors — a kind of anti-inflammatory drug — show promise as antidepressants. And no one should need to be told that nagging pain can be depressing or that depression seems painful.

But this also makes matters better. Claire recently asked why there aren’t better pain-relieving drugs. In particular, why aren’t there better alternatives to opiates? And if you treat pain as the incoming “signal” that opiates supposedly block, no wonder you’d wonder. But if pain is the brain’s opinion – albeit, an opinion not directly under our conscious control – then the world of pain treatment broadens. For example, treatments that simply improve mood are no longer just warm fuzzies that make people “feel better” about having pain; they show promise to ameliorate the pain itself. Treatments that modulate the immune system – hence inflammatory response – in increasingly targeted ways show promise to alleviate both noxious sensations and the “sickness behavior” that heightens pain sensitivity without causing as much collateral damage as do our most powerful anti-inflammatories. Even just teaching suffering patients “about modern pain biology leads to altered beliefs and attitudes about pain and increased pain thresholds during relevant tasks.”

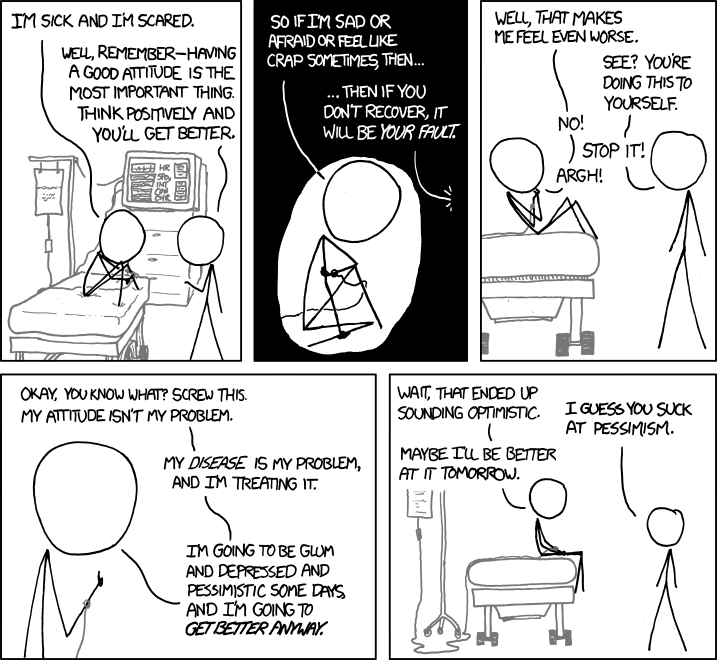

So what’s new in all this? First, teaching people about modern pain biology can add realism to the tried-and-true moral techniques for coping with pain. Without an appreciation that pain really is in the brain, but not under direct conscious control, it’s dangerously easy to over- or under-moralize pain. For example, the problems with the simplistic injunction to just “have a positive attitude” in the face of pain are well illustrated by the following comic:

If pain is reduced to a dualistic battle between incoming “pain signals” and our moral selves (with any sign of “losing the fight” condemned as moral failure), we lose sight of the fact that our physical and moral selves are aspects of the same whole, and are better off cooperating, not warring with each other.

Second, both pain and our conscious minds are phenomena emergent from our profoundly weird brains. Each influences the other, and yes, this means we do have some moral control over our pain. But not always in the way we like to think we do.

Published in Culture, Religion & Philosophy, Science & Technology

Heh. I’ve done the same thing, too, a few times.

Years ago, when I first tried the cold pressor test for pain tolerance, I aced it. Maximum safe time in the ice water. I recently tried it while pregnant, and yep, this time I wimped out. I had suspected pregnancy had left me more sensitive to pain. Of course, if that’s what I thought would happen, maybe it was a self-fulfilling prophecy…

Dee-dee dee-dee Dee-dee dee-dee…

Great post! I’m wondering: at what locations in the brain is pain registered (or sensed)? Apologies if you answered this, but I didn’t see it.

I’m not sure if all areas of the brain involved are entirely known yet. In fact, I suspect not. Pain is a conclusion the brain reaches from multiple portions of the brain communicating with each other at once.

^ The video embedded in the OP describes the “danger sensors” (nociceptors) alerting the spinal cord, which alerts the thalamus, after which a dialog between the frontal lobe and the posterior parietal cortex takes place. In the particular situation described in the video, it sounds like maybe the posterior parietal cortex has final say? But I don’t know if his one example categorize all pain perception (in fact I’d suspect not), or if it’s just a particularly good and simple example of how pain perception can work (which it certainly is). (Nonspecific inflammation also seems to sensitize pain perception, and that has no particular location.)

In Oregon, I think they don’t believe pain needs an explanation, just some meds prescribed by a licensed physician. Actually, they don’t even need the pain to do this. They can prescribe for something that’s not even an actuality yet. But what can you say, when Gaia wants you gone, you better get the message.

Except who is Gaia here for anyway? And who made Gaia?