Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

What My Students Said About Religion and Science

What My Students Said About Religion and Science

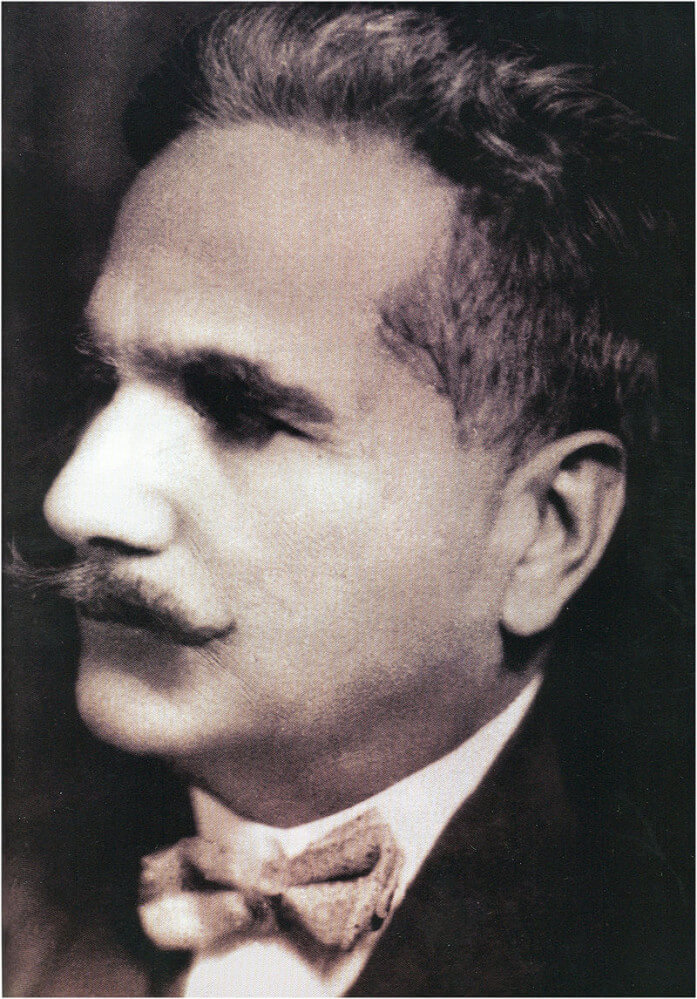

Iqbal

Meet Allama Iqbal: British knight, national poet of Pakistan, author of poetry in two languages (Persian and Urdu), author of philosophy in two languages (Persian and English), and the only major philosopher I know of who has an airport named after him.

Iqbal is an empiricist. Like William James (one of the visible influences on his thought), he strives for a thorough and consistent empiricism. This effort leads him to a neat little analysis of both religious and scientific knowledge. Before moving on, let that point sink in for a moment: Here’s a major philosopher who thinks a proper understanding of experience justifies both religious and scientific … knowledge.

Sound weird? Well, it does go against a host of popular assumptions. But it’s not that weird – nor is the reality of both scientific and religious knowledge a very unusual idea among careful and consistent thinkers.

Iqbal gives us this idea in The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, a very good book in which he attempts to integrate the insights of two intellectual traditions: modern science and religious mysticism — especially Sufism.

And Now It’s Time for a Story

The story will be told from my own fallible memories. But it’s a fairly accurate account of what happened.

So there I am in E-121 somewhere between 9 and 10 AM. I’ve just finished giving my students the gist of Iqbal’s argument for the legitimacy of both religious and scientific knowledge. I’d better review the argument for you. Knowledge, Iqbal says, is born of reflection based on experience. Two of the major varieties of knowledge are born of two major varieties of experience: scientific knowledge (born of reflection on sensory experience) and religious knowledge (born of reflection on religious experience). He says on these matters:

The facts of religious experience are facts among other facts of human experience and, in the capacity of yielding knowledge by interpretation, one fact is as good as another.

You can put this into an argument from the reality of scientific knowledge to the possibility of religious knowledge:

1. Science is a source of knowledge.

2. Science derives its warrant entirely from a combination of experience and reflection on experience.

3. So experience and reflection on experience is a source of knowledge.

4. There is such a thing as religious experience that can be reflected on.

5. So religious experience and reflection can also be a source of knowledge.

And Now, My Students Object!

Now my students begin to question Iqbal. Here are a few of the objections and replies (not word-for-word, but in words meant to capture the heart of the matter). My replies are, more or less, given on behalf of Iqbal because, today at least, I work for Iqbal – as on another day I work for Aquinas, Confucius, or Nietzsche.

Objection: But scientific knowledge can be subjected to tests, and religious beliefs can’t!

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: Says who? I don’t think Iqbal says that. What makes you think there is no such thing as a religious hypothesis that can be tested? For example, you might be able to confirm someone else’s religious experience by having your own religious experience.

Objection: But religion is based on subjective experiences, and science isn’t!

Iqbal International

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: Science relies on the experiences of various individuals. Those experiences are relayed from an individual scientist to everyone else by testimony. In this respect religion is exactly the same as science.

Objection: But religious thought is much harder to verify than scientific theories!

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: Maybe so. But so what? Iqbal’s analysis doesn’t depend on the ease of verification, or even the method of verification. Maybe it is harder to test a religious belief. Maybe not. (And maybe it varies by religion, and varies from belief to belief in both religion and science.) Maybe religious belief is less reliable than scientific belief, but that doesn’t affect Iqbal’s analysis either way.

Objection: But science is about matter, and religion and ethics are not. So they aren’t about anything real.

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: Are you sure about that? Remember what I told you about Plato and Pythagoras! Since triangles are composed of perfectly straight line segments without width, they can’t be made of matter, and you can’t see them. But you’re pretty sure you know what they are, and since you don’t know what doesn’t exist triangles must exist, and they must be non-physical realities known through the mind rather than through sensory experience. So maybe non-physical reality is just as real as physical.

Objection: But scientific thought is concrete, and religion is abstract, and concrete reality is so much easier to know.

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: Consider the X beliefs. Science depends on knowledge of them. But try explaining how we know them without being abstract. If you’re going to object to abstract knowledge, you’re probably going to have to object to science if you want to be consistent!

Objection: But what about the conflicts between the evidence of religious experience and the scientific evidence?

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: What about the conflicts between scientific evidence and scientific evidence? These conflicts come up all the time, and scientists manage them on a case-by-case basis, choosing one theory over another based on what evidence is more solid or what interpretation of the evidence is better. There are also conflicts between religious experience and religious experience, and religious believers have to deal with them in the same way. Well, it’s the same with conflicts between religious and sensory experience: If a scientific theory clashes with a religious view, you have to evaluate the experiences and the interpretation of them. In such a conflict, the best combination of solid evidence and good interpretation of the evidence wins! So, you see, this objection counts against science no less than against religion; rather, it counts against neither.

Objection: But moral beliefs are relative because in different cultures people have thought different things about morality.

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: Your unstated premise is that whatever different cultures think differently about is not objectively true. Different cultures have thought different things about astronomy. Does that mean that there is no objective truth about whether the earth orbits the sun? If this is a criterion for truth, science is condemned as relative along with religion!

Objection: But scientific knowledge is so much more systematic than morality!

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: Not necessarily. You may think this is necessarily so, but you are mistaken. It’s a good thing you’re taking this class, because later we’ll talk about Kant and Aristotle and Mill! Their analysis of morality is more systematic than science!

(By the way, I may have been mistaken in that last point. Is science, as a whole, less systematic than Aristotle and Mill? Maybe. I’m not sure. It’s definitely less systematic than Kant. Everything is less systematic than Kant.)

I suspect many of my students were all along motivated largely by the tension between evolution and traditional monotheisms — perhaps thinking incorrectly that evolution is a test for rationality. And now, with very little time left before class dismisses at 9:50, one of my students finally asks about evolution directly.

Objection: But what about evolution?????

Reply on behalf of Iqbal: In a clash between scientific and religious beliefs, you evaluate the evidence on which the beliefs are based, and you evaluate the interpretation of the evidence. In this particular case, Iqbal thinks the view that God created the earth in a manner inconsistent with evolution is based on a poor interpretation of the evidence from the Quran, which he happens to read non-literally in this case. So Iqbal is a theistic evolutionist.

And my final remarks, as time in class is running out, are something like this: I’m not saying that religious and scientific knowledge are entirely alike in degree of certainty or in method of verification. I’m not saying they are exactly the same kind or same quality of knowledge. And I’m not saying there aren’t good objections to Iqbal’s view of religious knowledge. But let’s be sure to offer good objections that don’t undermine science while we’re trying to promote it!

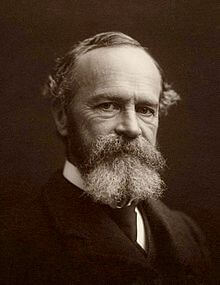

James

The End of This Essay At Last

Many of these objections were old territory for me, for I long ago put them into the mouth of the Grey Robot.

I do concur with Iqbal in this particular argument – though not necessarily in all the material related to the argument in his very good book.

But my goal was not to convince my students to agree with Iqbal. My main goals were to get them thinking, challenge a presupposition richly deserving to be challenged, and introduce them to a neat philosopher.

This was Intro to Philosophy; I’m sure my upper-level students would have given some better objections if they’d tried. For that matter, some of the lines of thinking in the Intro course, had they pressed on with them, might have led to a serious concern with Iqbal. (And I might well have not had any answers.)

Still, it’s amazing how often poor objections and double standards are used against the rationality or knowability of religious beliefs. Well spoken were those words of William James:

Of some things we feel that we are certain: we know, and we know that we do know. There is something that gives a click inside of us, a bell that strikes twelve, when the hands of our mental clock have swept the dial and meet over the meridian hour. The greatest empiricists among us are only empiricists on reflection: when left to their instincts, they dogmatize like infallible popes.

Now, I am gradually working towards devoting all of my Ricochet posts for an extended period of time to the topics of a couple of book projects I’ve been working on. I hope this is one of the very last before I get around to that. But here it is, whether or not it be one of the last.

And I plan to give you a sequel later, in which I’ll look at one aspect of this matter a bit more systematically. Specifically: How is religious belief to be verified or falsified?

Author’s notes:

- Edited since initial posting. See comment 32 and comment 66, below.

- The conversation below eventually led to an overview of the philosophy of science and a new presentation of the major issues I discussed with one of my primary interlocutors. See comment 229, below.

That will probably help. I hammered out some replies. I think I’ll look over them in the morning before posting them.

Thanks, gentlemen. Have fun while I’m gone!

Have you been saying this all along? Till now I’d only noticed other things you’d said.

Let me try to paraphrase:

Did I get that right?

It would explain a lot if I did. You know, that doesn’t sound so bad. It sounds a lot better than some of your more skeptical (or contradictory of incomprehensible) claims about us never knowing the truth.

In order to make this kind of objection to my definition of knowledge you don’t have to say we humans never know the truth. It looks to me like you just have to say these three things:

Continued:

(Continued)

I hope that was clear and precise enough. You said number 1 clearly enough, though I never understood numbers 2-3 before.

Now I don’t accept number 2. (If I ever have it’s been quite some time.)

I think this is what Mack the Mike was explaining back on page 15: To claim to have a warranted belief simply is to claim to have truth, because you can’t believe A without believing A to be true. The sentences “I have a warranted belief that A” and “I have a warranted true belief that A” and “I know A” all mean the same thing. So there is no claim made on top of that other claim.

Larry3435,

Clear speaking does matter, and the locution “know that we know” is a great example. (Even the great epistemologist Roderick Chisholm misused it.)

We generally know what it’s getting at: To say “I know that I know” is to say “I have certainty.”

But if we look at the literal meaning of the words, to know that one knows is simply to know.

I can say “I know Trump’s the wrong man for the job,” and I can say “I know that I know Trump’s the wrong man for the job.” Literally, it means the same thing: The claim I say I know in the longer sentence has all and only the same content as the claim I say I know in the shorter sentence. (If I have a warranted belief that A, then I believe that it’s true and that I’m warranted in believing it. So to say I have a warranted belief that A is also to say I have a warranted true belief that A. So to say I know A is to say that I know that I know it.)

Of course, I shouldn’t talk like that without extremely good evidence–because of the way we use that locution as connoting certainty.

But your argument, Larry, insofar as it depends on that locution, depends on taking it literally, and on that literal meaning adding a claim it actually doesn’t add.

Yeah, you got it right enough. A little bit convoluted in the phrasing, but the point gets made. The (“skeptical, contradictory or incomprehensible”) part about never knowing the truth works its way into your summary in the phrases “maybe it’s true, maybe it’s not” and “certainty which humans cannot possess.” Those are valid rephrasings of my point. And if you go back and re-read some of my comments, I’m sure you will see that I have been saying this all along. Saying it pretty clearly, in my biased opinion.

That’s why I don’t use the expression “know that I know” to express certainty. I have said all along that certainty is the issue. But, I use the expression “I believe with certainty.” This is also why I draw the very important distinction between “I believe with a very high degree of certainty” and “I believe with absolute certainty.” A “very high degree of certainty” is fine, and I accept that as a working definition of knowledge. “Absolute certainty” is not fine, because valid absolute certainty is not possible. If a human thinks he is absolutely certain, meaning there is no possibility of falsity in his beliefs, then he is making a mistake and is close-minded.

I’m sorry, but you are just mistaken here. There is difference between “I have a warranted belief that A” and “I have a warranted true belief that A.” The difference is the addition of the word “true.” When you say that there is no difference between those phrasings, you are saying that adding the word “true” makes no difference. That much I agree with. Adding the word true makes no difference. I have said repeatedly that all we have is our conclusions, based on the evidence; adding the word “true” adds nothing.

But then the question remains, why are you adding the word “true” if it makes no difference? It sure sounds like it makes a difference. If I accept your dictionary definition of truth as being an accurate reflection of reality, then it does make a difference. Because it banishes uncertainty. And I have already explained what is wrong with banishing uncertainty from your thinking.

So if you agree that adding the word “truth” makes no difference, then how about you just drop that word and avoid all the confusion?

Yes I can. And I do. If I have a warranted belief, then I claim to have a degree of certainty about that belief. I never claim that the belief is true, unless it is a sloppy shorthand for my high degree of certainty. I am not immune to sloppiness. Not by a long shot. But if you call me on the sloppiness, I will certainly clarify that I do not claim “truth” about any of my beliefs. Because in my vocabulary, “truth” is infallible, and I do not use that word to describe beliefs that I know full well might be wrong.

I have stated repeatedly that when I say that humans never “know” the truth I am saying that humans are never “certain” of the truth. Those statements are synonymous to me. I have said that we search for the truth, and we approach the truth, and we can have a high degree of certainty about what we believe to be the truth, but we can never have perfect certainty that our beliefs accurately conform to the truth. They might (by happy coincidence). That possibility exists, for sure. But we cannot be certain.

So yes, your three point phrasing includes exactly what I am saying when I say that humans never “know” the truth.

If you are going to talk like this then maybe we should just quit. It seems we aren’t even speaking the same language.

The word is added because we are either giving a definition of knowledge or stating the conditions under which a belief is knowledge–or both. (I believe you had asked for both; I know you asked for at least one of the two.)

Here it all is (sandwiched) in (the two halves of) a nutshell:

The claim “I have a warranted belief that X” and the claim “I have a warranted true belief that X” mean the same thing.

But the sentences “Bob knows X” and “Bob has a warranted belief that X” do not mean the same thing–because he could be in error.

Warranted belief claims and knowledge are (frequently) different. But your argument (overviewed in # 422 above) depends on warranted true belief claims and warranted belief claims being different. But they aren’t.

(Ok, so really it’s just inverted pictures of the same half of a nutshell.)

No, that’s wrong. I don’t say they are different. I say that they are the same. I say that adding the word true adds nothing. It does not change the meaning. It is, quite literally, meaningless. And therefore, I would not add that word.

I am also saying that when you insist on adding that word, you must think it is important. You must think it adds something (even though you have conceded elsewhere that it does not). So my argument at #422 is my refutation of what I see as being the only thing you could possibly be adding (even though you deny it) which is the additional claim that your warranted belief is “true” in the sense that it perfectly conforms to reality.

That is the additional claim you (seem to me to be) making when you add the word true. Yet you deny that you are making that, or any, additional claim. So I ask again, why do you insist on adding the word “true”?

We’re probably not speaking the same language. I’m speaking English.

Would it help if I said “absolutely true” rather than just “true”? If I said that I can believe something without believing that it is “absolutely true.” I don’t think that the word “absolutely” should be necessary, because I think “truth” is absolute by definition. But if you need that word to understand me, please consider it added.

But I suggested that you did (number 2 from # 422), and you said (# 425), “you got it right enough. A little bit convoluted in the phrasing, but the point gets made. . . . Those are valid rephrasings of my point.”

So was # 422 a correct overview of your view or not?

I’ve answered that question. See # 431, above, and especially the nutshell therein.

On the contrary, your remarks constitute a direct rejection of the meaning of the English word “believe.” (See the dictionary.)

It might help me understand you, but it only shows once again how wrong you are. Remember: This is about your number 2 from comment # 422 (my words, but your own claim, as you professed).

Number 2 is plainly false. (See the dictionary.) Now we could reword it in this manner:

Now number 2 is false for a different reason. A claim to absolute truth would be a claim on top of the claim to have a warranted belief, but that definition of knowledge doesn’t entail that every claim to have knowledge is a claim to absolute truth.

Correct. That definition of knowledge doesn’t entail such a claim. That definition of knowledge is simply a part of my definition of knowledge. It’s your other definition of knowledge, where the word “true” actually means something, with which I disagree.

And please keep it straight. #422 is an accurate statement of how I refute your assertion that the word “true” means anything in the phrase “warranted true belief.” It doesn’t mean anything. You even admit that it doesn’t mean anything. And no, you have not explained why you add superfluous, meaningless words in your definition. Maybe you explained in the language known as “nutshell,” but as I said I am speaking English.

All your complaints here have been answered above, most importantly in # 431.

Although it’s technically a redundancy, I’ll make one remark here in hope that it makes things clearer to you:

If I were to say “I have a warranted belief that Trump is the wrong man for the job,” adding the word “true” to my claim would add nothing, for I’ve already said that I have a belief I consider true.

But let’s say you responded to me, “Your do indeed have a warranted belief there;” and then you added “and it’s a true belief.” Your addition really does add something, because you had not yet said that that belief is true.

I have cross-examined thousands of witnesses during the course of my career, so I am well acquainted with the tactic of giving an incoherent and non-responsive answer to a question, and then refusing to explain any further by saying “I already answered that.” But I must admit, I have never seen anyone try this tactic when their earlier answer had consisted of showing me a picture of a peanut.

You still haven’t seen it. The earlier answer was given in a nutshell. It consisted or a few lines of text which you have evidently either not read or not understood. They really did answer those complaints.