Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Are the GOP 2016ers Really Ignoring the Economy?

Are the GOP 2016ers Really Ignoring the Economy?

The WaPo’s Catherine Rampell certainly sums up what I was thinking during the recent GOP debate:

The WaPo’s Catherine Rampell certainly sums up what I was thinking during the recent GOP debate:

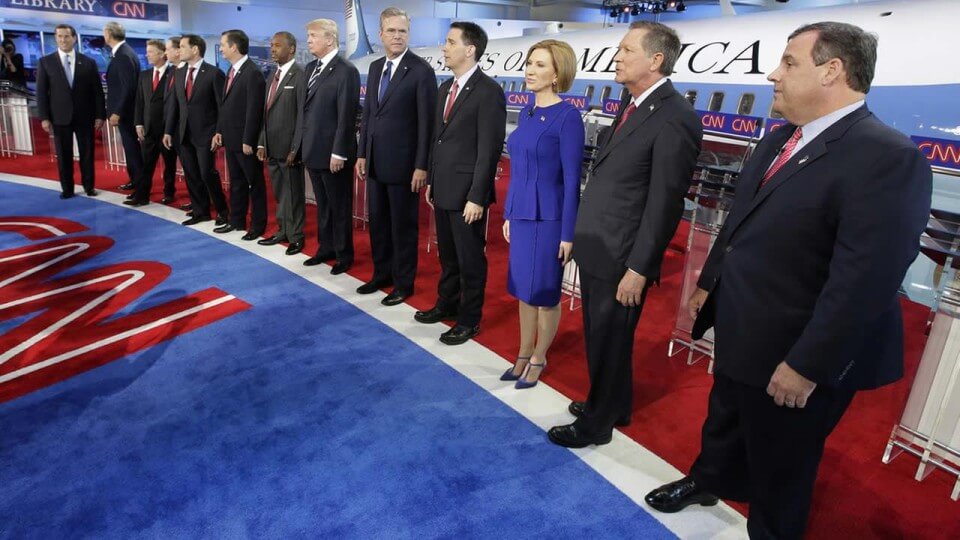

To the great disappointment of econo-nerds everywhere, the economy was almost entirely ignored during Wednesday’s Republican presidential debate. Over the course of three hours, the moderators and debaters found time for but a few minutes of discussion on the economy, most of that on the minimum wage. There was almost nothing on jobs; nothing on inflation; one throwaway mention of trade; and nothing on the Federal Reserve’s impending interest-rate decision, which would be announced the following day (spoiler: the Fed kept rates at zero percent— more on that in a bit). And so the econ-Twitterverse cried out: Whither the economy? Attention must be paid!

Rampell speculates Republicans don’t want to talk so much about the economy because of its slow improvement. Sort of makes sense.”The economy is not as strong as it should be” is a less compelling narrative than, “The economy is in the tank.”

As it happens, I also wrote about this issue in a post yesterday, “How will the GOP deal with the slowly improving economy?” I partly blamed the debate moderators. Still, the candidates could have done more themselves, especially given that the moderators held the reins pretty loosely. But maybe they didn’t for the reason Rampell cites. Indeed, recall that the Goldman Sachs election forecasting model finds the economy is a tailwind for Democrats, not the GOP. Now Rampell’s colleague, Jim Tankersley took issue with the thesis, via Twitter, and makes a good point:

Respectfully disagree with @crampell here: GOP candidates are campaigning on econ issues, just not in debates … Which is why it’s a mystery that moderators aren’t asking about economy more. … One possibility: The candidates aren’t disagreeing hugely (save Trump) on econ — they all want some variations of pro-growth tax cuts.

The GOP has policy ideas. But what I see less of is the sort of macro theorizing about what is really wrong with the US economy — both in terms of growth and how the fruits of that growth are dispersed. I would like to see the candidates talk deeply about those issues rather than simply ticking off this or that policy to supposedly boost GDP growth. More on their diagnoses, please.

Why has high-end inequality risen and what are the growth impacts? How is automation affecting workers today and how might it in the near-to-mid future? What do they make of the “secular stagnation” thesis? Might the economy actually be stronger than we think because currents stats do a poor jobs on measuring the digital economy? What factors will make it harder to grow as fast in the future as in the postwar era? Is the link between productivity and wages broken? How are the economic challenges of today different than those when Ronald Reagan or Bill Clinton or George W. Bush came into office?

For an idea of how it sounds when a politician does talk about such ideas, I highly recommend reading this talk at AEI by Britain’s George Osborne:

Published in Economics, PoliticsThis prediction, that the link between living standards and economic growth has broken, also leads its proponents to the same prescription: more government spending on welfare and the costs of economic dependency. But it too can be proved wrong if we follow a different approach.

To begin with, this argument about the broken link is not well supported by the facts. As Greg Mankiw has pointed out for the US, on a superficial reading, the data appears to show that real median incomes grew by only 3% over the entire period from 1979 to 2007. And that sounds like there is a big problem. But in fact, once you take account of changes in household composition, lower taxes, health care benefits and other forms of remuneration, then that number turns into a 37% real terms increase. Of course, that’s not to say that inequality doesn’t matter. It does. The great recession made our countries poorer and times have been difficult for British and American families. But in the UK, the evidence shows the growth supports rising living standards. Recent work by academics of the London School of Economics and our own analysis at the treasury has found no evidence that employee compensation has become detached from GDP growth in recent decades. Previous results that appear to show a break disappear once you take into account rising pension contributions and my previous – the previous government’s payroll taxes in the UK. And that is one reason why the labor share of national income in the U.K. has stayed constant over the last decade.

Nor does the evidence support the so-called hollowing out hypothesis in the UK – the idea that middle-skill and middle-income jobs are disappearing with most of the growth in employment either at the top or the bottom of the distribution. While some traditional mid-level occupations have shrunk or moved down the income scale, new ones are being created to take their place. So we have less middle-paid production line and secretarial jobs, but a lot more middle-paid jobs in IT and professional services. Overall, there has been little change in the proportion of people in middle-income jobs in recent years. And after rising during the industrial restructuring of the 1980s, as it did in many countries, the level of inequality in the U.K. has been fairly constant for two decades. And according to the latest data, it’s at its lowest level since 1986.

So the long-term link between economic growth and living standards has not been broken. When the economy shrinks, people get poorer. And the only way to ensure that people are better off is for the economy to grow, But we, nevertheless, face a tremendous challenge. The very legitimacy of our free market depends on the promise that effort is rewarded and prosperity is shared. In recent decades, the premium earned by highly skilled, highly qualified people has increased even as the number of highly skilled people has increased. And that tells us something important about the insatiable demand for higher skills in the modern global economy. The flipside of that is that the downside of having low skills has increased, too. Harvard economist Claudia Goldin and Larry Katz famously posited a race between education and technology. And, more recently, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee have been among those writing about the race against the machine – the risk that increasing deployment of artificial intelligence and driverless cars and other digital technologies will lead to unemployment. …