Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Teaching Freedom the Bastiat Way

Teaching Freedom the Bastiat Way

For many years I’ve kept a personal blog. Nothing too big or grand. There I discuss mostly politics and history. From time to time I get e-mails from parents asking for reading lists. What books will best impart an understanding of freedom? Like many parents, they’re unsatisfied with the low-thinking busywork their children get assigned. They’re even less satisfied with the flagrantly statist and collectivist slant of their course material.

For many years I’ve kept a personal blog. Nothing too big or grand. There I discuss mostly politics and history. From time to time I get e-mails from parents asking for reading lists. What books will best impart an understanding of freedom? Like many parents, they’re unsatisfied with the low-thinking busywork their children get assigned. They’re even less satisfied with the flagrantly statist and collectivist slant of their course material.

What these parents are looking for is something that will inoculate their children from the pernicious ideas that circulate in the public school system. While most of the people I’ve dealt with are devout Christians, a very large number are entirely secular. All of them are thoughtful parents who are terrified of raising unskilled, unemployable children who will whittle away their lives playing revolutionary.

It is the irony of the modern world that the most successful socio-economic system in history, Anglosphere-style capitalism, is the least defended. The times have been worse. Scroll back to the 1930s when, with the exception of men like Friedrich von Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, there were very few serious voices raised in the defense of economic liberty. Today much of the English-speaking world boasts a network for think tanks, endowed chairs, and prominent commentators. Without them we would be in a far worse position than we are.

Still, it doesn’t seem like enough. The statists of all parties control the schools, universities, and media establishments. The thoughtful parent needs to develop “counter-programming” for their children. Yet for many parents there is almost too much choice. There is no shortage of websites, books, pamphlets, video presentations, and online lectures that refute every aspect of the statist project from every angle imaginable. So, where to start?

What I usually recommend is to start with the child. What type of child is he? Does he show signs of being a budding intellectual? Football hero? Business tycoon in the making? Not really sure? Giving the wrong type of information to the wrong child usually winds up being a frustrating experience for everyone. Keep in mind the first rule of public speaking: know your audience.

The biggest mistake I see parents making is dumping great, big lumps of book onto unsuspecting students. It must be a terrifying experience. So here is a young person of 16 or 17 being confronted with Milton Friedman, Ayn Rand, and Ludwig von Mises. While these authors were capable of brevity and wit, their preferred method was long and thorough. A hardcover copy of Atlas Shrugged is thick enough to subdue most woodland creatures. It may not be quite as successful with teenagers.

The intellectual types will, sooner or later, wade their way through all this stuff. It might take one, two, or three passes, but they’ll figure out what these thinkers were trying to say. The future entrepreneur, a natural extrovert always looking for an opportunity, is likely to be bored out of his mind reading the Great Books of Freedom. There are exceptions, but don’t count on exceptions.

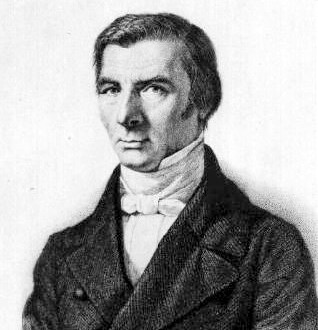

For most people, keep it simple. This isn’t because they lack the intelligence to grasp more sophisticated ideas, it’s that they lack the patience to do so. Everyone has their own particular aptitudes and insights. Work with those aptitudes, not against them. When the kid is bright, but not keen, I always recommend the great French writer Frederic Bastiat.

Among libertarians, Bastiat is an honored hero, a defender of free markets from a country with a deep streak of anti-capitalism. The French may have given us the term laissez-faire, that doesn’t mean they agree with it. Among conservatives, Bastiat is a name occasionally mentioned but little discussed. His writings focused mostly on economic questions and he lacked the intellectual heft of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, or John Stuart Mill. Yet what he lacked in technical depth he more than made up for in fluency and clarity of thought. Frederic Bastiat was the Great Communicator of economic liberty.

His best work, the work that comes up immediately whenever your search for his name, is a slim volume published in that last year of his life: The Law. I had spent years reading the great intellectual defenders of freedom, working through their complex and often arcane ideas. Yet it all made sense after I read The Law. Bastiat had taught me nothing new. Instead Bastiat taught me to think plainly and directly from first principles.

The great value of The Law is that it can be used both as a primer for more sophisticated studies, as well as a teaching tool for those largely uninterested in ideas or political discussions. The Law can be read in an afternoon and hold the attention of the jock, the nerd, and the Type-A personality. The only thing that I’ve seen that comes close in both clarity and concision are the excellent videos put out by Prager University.

Here is a sampling of Bastiat’s prose. On the subject of “Property and Plunder” he writes:

Man can live and satisfy his wants only by ceaseless labor; by the ceaseless application of his faculties to natural resources. This process is the origin of property.

But it is also true that a man may live and satisfy his wants by seizing and consuming the products of the labor of others. This process is the origin of plunder.

Now since man is naturally inclined to avoid pain — and since labor is pain in itself — it follows that men will resort to plunder whenever plunder is easier than work. History shows this quite clearly. And under these conditions, neither religion nor morality can stop it.

When, then, does plunder stop? It stops when it becomes more painful and more dangerous than labor.

It is evident, then, that the proper purpose of law is to use the power of its collective force to stop this fatal tendency to plunder instead of to work. All the measures of the law should protect property and punish plunder.

But, generally, the law is made by one man or one class of men. And since law cannot operate without the sanction and support of a dominating force, this force must be entrusted to those who make the laws.

This fact, combined with the fatal tendency that exists in the heart of man to satisfy his wants with the least possible effort, explains the almost universal perversion of the law. Thus it is easy to understand how law, instead of checking injustice, becomes the invincible weapon of injustice. It is easy to understand why the law is used by the legislator to destroy in varying degrees among the rest of the people, their personal independence by slavery, their liberty by oppression, and their property by plunder. This is done for the benefit of the person who makes the law, and in proportion to the power that he holds.

I remember sitting in a university library and reading the above. The word that hit me was “plunder.” That’s what Big Government is really all about, when you get past the slogans, the rationalizations, and the rhetorical legerdemain. Bastiat was not an anarchist, he was a classical liberal. He recognized a need for government, expressed here by using the term “law.” He describes the abuse of government power as the “perversion of the law.”

Bastiat’s refusal to mince words is his great strength as a writer. He is not a wide-eyed fanatic. In calm and logical prose he calls a thing by its correct term. Not subsidy, or grant, or benefice but plunder. It’s this insight that leads us to Bastiat’s most famous and important dictum:

Government is the great fiction through which everybody endeavors to live at the expense of everybody else.

Now reexamine all the great political issues of today and apply that simple principle: The rhetoric melts away and a cold and unpleasant reality remains. The final chapter of The Law is entitled simply Let Us Now Try Liberty and finishes thusly:

God has given to men all that is necessary for them to accomplish their destinies. He has provided a social form as well as a human form. And these social organs of persons are so constituted that they will develop themselves harmoniously in the clean air of liberty. Away, then, with quacks and organizers! Away with their rings, chains, hooks, and pincers! Away with their artificial systems! Away with the whims of governmental administrators, their socialized projects, their centralization, their tariffs, their government schools, their state religions, their free credit, their bank monopolies, their regulations, their restrictions, their equalization by taxation, and their pious moralizations!

And now that the legislators and do-gooders have so futilely inflicted so many systems upon society, may they finally end where they should have begun: May they reject all systems, and try liberty; for liberty is an acknowledgment of faith in God and His works.

That was written more than 165 years ago. It’s relevance has only grown.

Published in Economics, Literature

I have read Bastiat. Your point is well made. His logic is cogent and compelling.

You used this quote and it is a gem.

Thank you. This was very well written. It belongs on the other side.

Nice post. Bastiat’s The Law had a similar effect on me when I first read it. Like opening the window on a dark, stuffy room.

Our problem is, lacking faith in God, we logically lack faith in his works. Instead we’re left with the rule of the demagogue, like Obama or Trump.

Is Milton Friedman quite as averse to brevity as Rand and von Mises are? I seem to recall Free to Choose and Capitalism and Freedom both being rather short. Not knocking Bastiat, though. Not at all.

Midget,

I was thinking of his more technical tomes. I don’t think either Free to Choose or Capitalism is shorter than The Law.

Thanks

Sure, not shorter. But I think not very much longer – especially when compared to the technical tomes, or “Human Action” or “Atlas Shrugged” :-)

I see what you’re saying Midget.

All the best.

Great post and gorgeous picture!

It was his “Broken Window Fallacy” that first got my attention. If you wrap your brain around that little essay, you can see a bad economic idea from a mile away.

Very nice post. I’m convinced. I’ve read a little bit of Bastiat, but now I will have to pick up a copy of The Law.

I read the entire book lounging poolside one afternoon with a cool drink at my side. I was so impressed with The Law, I went on a tear reading Sowell, Hazlitt, and other great economic thinkers. But I always go back to Bastiat’s tiny book for its clarity and impact.

Bastiat + Amazon + Kindle = excellent library on the cheap:

The Law Kindle Edition $0.99;

Essays on Political Economy Kindle Edition $0.00;

The Bastiat Collection Kindle Edition $2.99;

What Is Free Trade? An Adaptation of Frederic Bastiat’s “Sophismes Éconimiques” Kindle Edition $0.00;

Frederic Bastiat on What Is Money ? Kindle Edition $1.09

There are several of his books on the Project Gutenberg website.