Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Athens on the Potomac

Athens on the Potomac

Financial experts in New York, London, and Brussels have tut-tutted Greece’s economic travails as Athens considers its future with the European Union. Why did they borrow so much money? How can they ever pay it back? Do they think that much debt is sustainable?

Financial experts in New York, London, and Brussels have tut-tutted Greece’s economic travails as Athens considers its future with the European Union. Why did they borrow so much money? How can they ever pay it back? Do they think that much debt is sustainable?

Instead of pointing fingers at the innumerates running Athens, they should consider our own situation. Jason Russell of the Washington Examiner shows how America’s debt projections look suspiciously like Greece’s recent history.

With all the chaos unravelling in Greece, Congress would be wise to do what it takes to avoid reaching Greek debt levels. But it’s not a matter of sticking to the status quo and avoiding bad decisions that would put the budget on a Greek-like path, because the budget is on that path already.

A quarter-century ago, Greek debt levels were roughly 75 percent of Greece’s economy — about equal to what the U.S. has now. As of 2014, Greek debt levels are about 177 percent of national GDP. Now, the country is considering defaulting on its loans and uncertainty is gripping the economy.

In 25 years, U.S. debt levels are projected to reach 156 percent of the economy, which Greece had in 2012. That projection comes from the Congressional Budget Office’s alternative scenario, which is more realistic than its standard fiscal projection about which spending programs Congress will extend into the future.

If Congress leaves the federal budget on autopilot, debt levels will soar. Instead, spending must be reined in to avoid a Greek-style meltdown.

While we’re right to be concerned about 2040, the U.S. is in deep trouble now. Yet if you mention the debt to most Americans, they’re either confused or indifferent. “But Obama lowered the deficit.” “Just print more money.“ “It’s Reagan’s fault!”

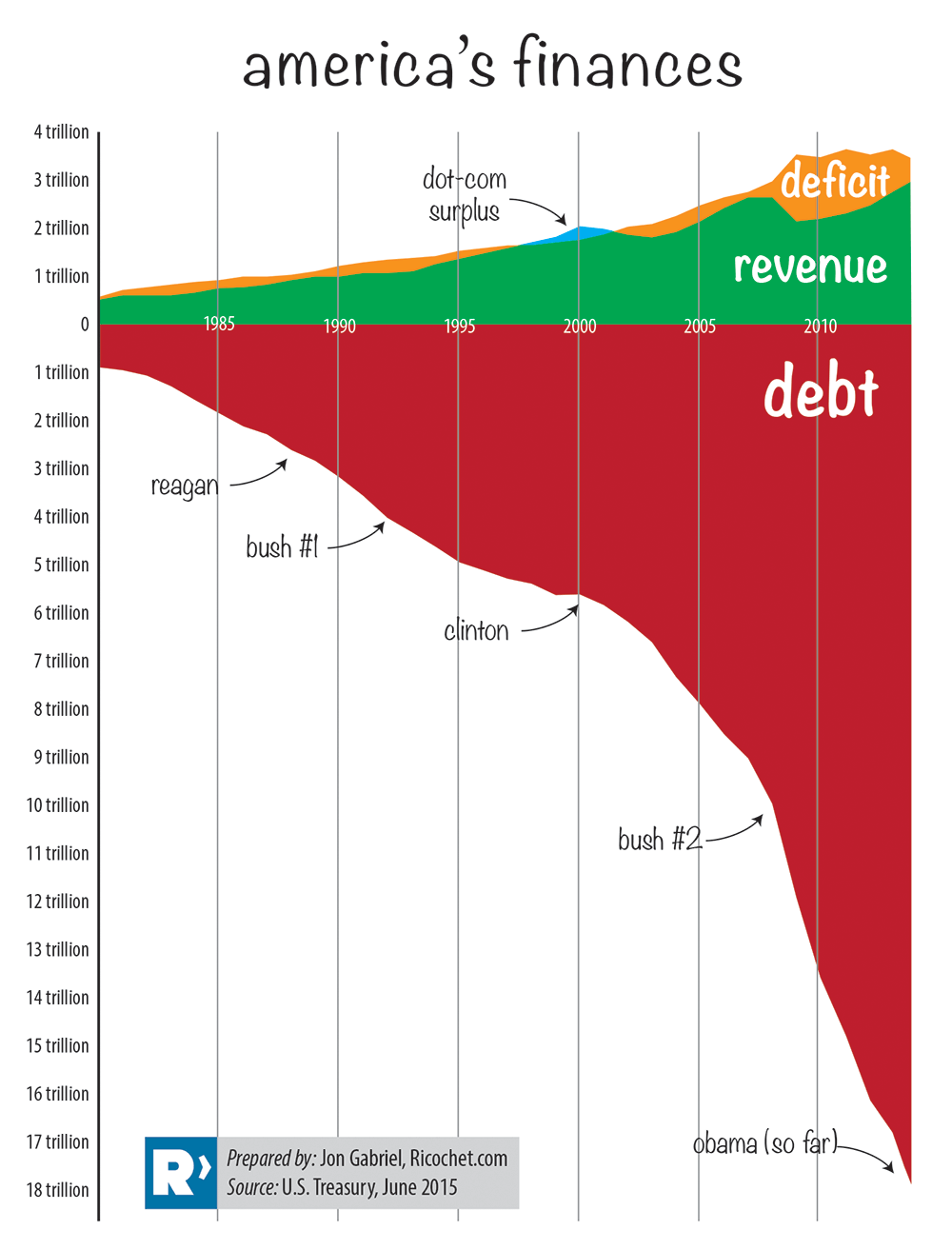

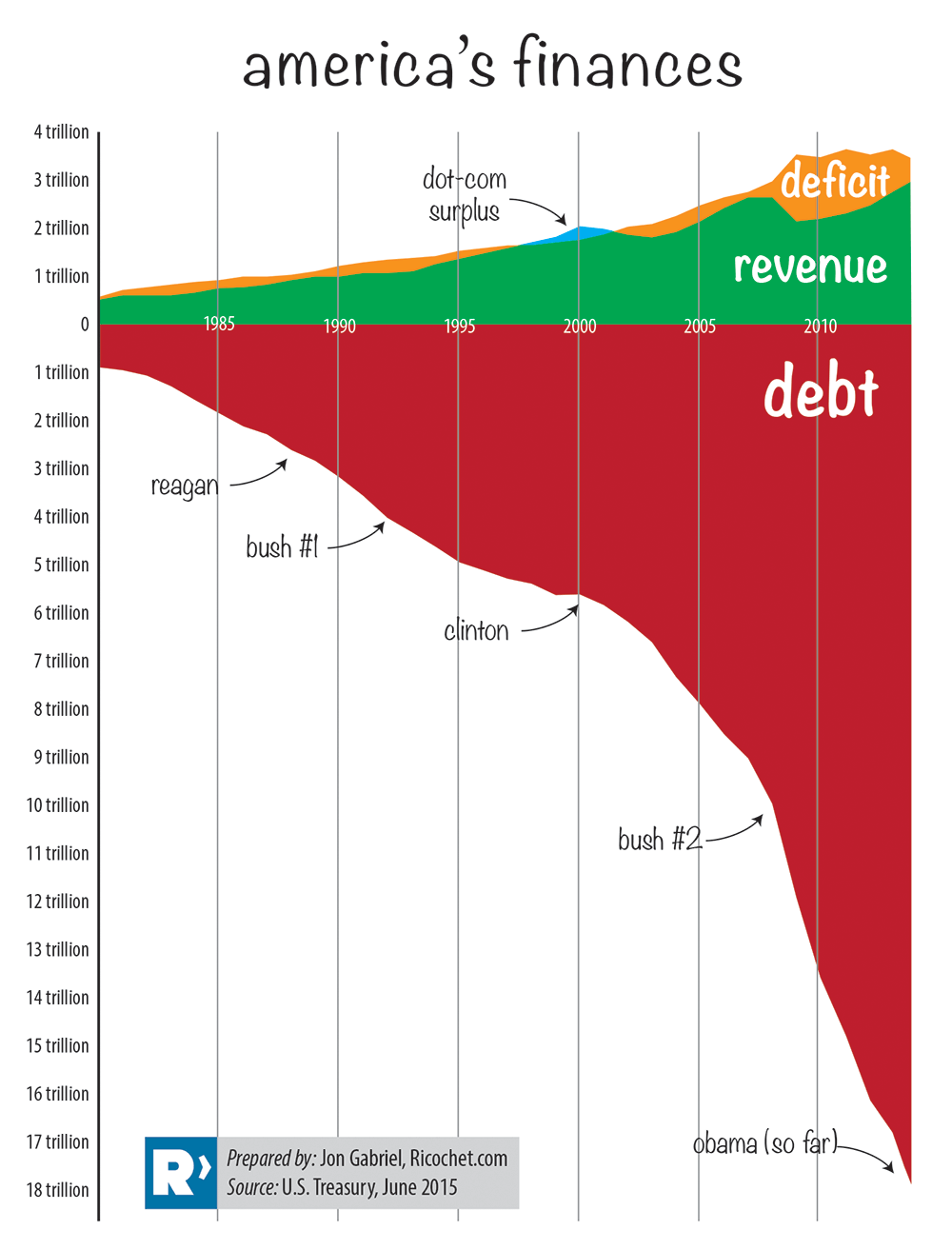

Since most graphs look like this, I created my own user-friendly debt chart focused on three big numbers: Deficit, revenue and debt. (My first version was published a couple of years ago. This one is updated with the most recent figures).

It’s an imperfect analogy, but imagine the green is your salary, the yellow is the amount you’re spending over your salary, and the red is your MasterCard statement.

The chart is brutally bipartisan. Debt increased under Republican presidents and Democrat presidents. It increased under Democrat congresses and Republican congresses. In war and in peace, in boom times and in busts, after tax hikes and tax cuts, the Potomac flowed ever deeper with red ink.

Our leaders like to talk about sustainability. Forget sustainable — how is this sane?

Yet when a conservative hesitates before increasing spending, he’s portrayed as a madman. When a Republican offers a thoughtful plan to reduce the debt over decades, he’s pushing grannies into the Grand Canyon and pantsing park rangers on the way out. While the press occasionally griped about spending under Bush, they implore Obama to spend even more.

When I posted the earlier version of this chart, the online reaction was intense. A few on the right thought I was too tough on the GOP while those on the left claimed it didn’t matter or it’s all a big lie. Others told me that I should have weighted for this variable or added lines for that trend. They are free to create their own charts to better fit their narrative and I’m sure they will. But the numbers shown above can’t be spun by either side.

All of the figures come from the U.S. Treasury and math doesn’t care about fairness or good intentions. Spending vastly more than you have, decade after decade, is foolish when done by a Republican or a Democrat. Two plus two doesn’t equal 33.2317 after you factor in a secret “Social Justice” multiplier.

If our current president accumulates debt at the rate of his first six-plus years, the national debt will be nearly $20 trillion by the time leaves office. That is almost double what it was when he was first inaugurated.

Like many Americans, I haven’t had the privilege of visiting Greece. Unfortunately, Greece will be visiting us unless we change things and fast.

Published in Economics

So you’re in essence showing an example of what every economist says…that you can’t beat the market over the long run…as evidence of why economists are dumb.

Can’t say I’m surprised at this point, Tuck.

For America?

That wasn’t what happened to Long Term Capital, AIG. But its pretty clear you’re operating in a fact-free zone.

Pick a country Tuck. At this point, it doesn’t matter. You might as well pick Antarctica. You clearly don’t even understand what an interest rate is, never-mind what it means.

So you’re saying you’ve never taken an econ or finance class in your life? Well, that explains a lot then.

Now, you are not making an argument in good faith. I have proposed no policy, in my first post, I agreed with you on cost of money, as I did in the second post.

Now, you are deciding what I say means, and ignoring what I say it means.

I am not sure how that advances your argument at all.

anonymous: Yes. but the point is that when you’re 18 trillion in the hole and borrowing money not just to roll over the principal of your debt as it matures, but also to pay the interest, what matters is what the prevailing interest rate is when you have to do the roll-over. As of the end of 2012, according to the U.S. Treasury, the mean maturity of its outstanding debt was around 65 months, or a tad more than five years. That means that within five years, half of that debt coming to term needs to be re-financed at prevailing interest rates, whatever they may be at the time.

Which is a great argument for borrowing more when the rates are low, so that the interest you have to pay back is lower.

Except that that’s not what happens here.

Again, low interest rates now means you have less interest to pay back in the future.

Which is precisely why you buy cheap.

No, I’m saying your argument is a perfectly fair argument to make, but it’s not a philosophical argument. A math argument isn’t philosophy. So I don’t know why that was the most important point of your post? I though the rest was more important.

That’s great.

Than that’s a good illustration of why your “bet” example means the reverse.

I.e., when you got a bank, you want them to give you a loan at the lowest possible interest rate. Preferably 0%.

From your perspective, this is good. From the bank’s perspective, this is bad. They make no money on you.

So your bet example is in essence saying “if I were a bank, would I make more money lending out at 0% or at 2%?” Of course at 2%!

But we’re not the bank. We’re the borrower.

We want the bank to make no money from us. But of course, the bank is only going to be willing to give you a 0% loan if its looking for a safe investment.

So the return they get is a function of the risk they are willing to take. Your “bet” was whether or not the bank will make money. But we, as the borrower, don’t want the bank to make money from us.

Your argument in fact is the basic concept of capitalism: consumers want firms to make no profits…firms want to make the most profits. The market decides who gets more pull on that.

More fundamentally, the argument is about taxes vs debt.

Taxes have a cost associated with them. Taxes aren’t “free”. They have an opportunity cost. Hence, whether to use debt, and how much debt, depends on the opportunity cost of taxes. If you think the opportunity cost of taxes is less then the cost of debt, then by all means use taxes

But the reality is that it’s almost never less.

If the government came and said to you: John, you owe us $40k in taxes. Now, we’ll give you the option of paying the $40k you owe us today, or you can pay us back in 5 years at 0.5% interest.

Which one do you chose? You will have to pay more in the future, true, but the opportunity cost of that $40k may be even more than the 0.5% interest you’ll have to pay.

If you take that $40k today, invest it in some productive activity which will give you a return, as long as the return you expect to get is greater than the 0.5% interest, then you’d be better off paying it in 5 years. Not today. You’ll be ahead.

In the actual US government situation, it’s even better than that, since most of the “debt” is owned to the US government anyway. It has implications for monetary policy, which is why the Fed owns it. But that’s a separate issue.

Getting back to the OP (I agree with Rahe), even an appreciation of deficit finance as a valuable tool shows that like any valuable tool, it can be abused and certainly has been.

Our *least* destructive solution is to create client states as sandboxed customers. I didn’t say it was right or good or ethical.

Just not in the US example.