Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

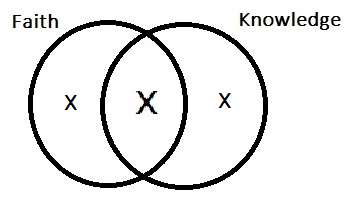

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

Knowledge and Faith Can Be the Same Thing

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

It is commonly assumed that an item of knowledge and an article article of faith can never be the same thing. This assumption is mistaken. In this post, I will explain only one point: trust in authority can be a source of knowledge. That’s what faith is: trust. It’s still the first definition of “faith” in the dictionary. Also see the Latin fides and the Greek pistis.

So don’t believe the hype that categorically separates faith from knowledge. This separation ranges from the view William James attributes to a schoolboy (“Faith is when you believe something that you know ain’t true”) to Kant’s more sophisticated idea that “I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith” (in beliefs that might well be true).

We should also reject the hype that says that an argument from authority is necessarily fallacious. The best logic textbook in print will tell you otherwise. It will even tell you that there is such a thing as a valid argument appealing to an infallible authority! (“Valid” is a technical term in logic; be sure to look it up first if you’re inclined to complain that there are no infallible authorities.)

Arguments from authority are good or bad depending on what their content is: and primarily on what sort of knowledge the authority is supposed to have, and whether it is reasonable to suppose that the authority really has it.

So an argument from a reliable authority is a good argument, and an argument from an unreliable or untrustworthy authority is a bad argument.

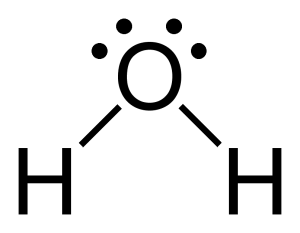

Protons and electrons: an article of faith

We must also dispense with the idea that science is the epistemological opposite of faith: one relying entirely on reason, one not at all. In actuality, religious faith usually relies on reason to varying degrees, up to and including this summary of Christian theology by Thomas Aquinas–quite possibly the most impressive bit of systematic reasoning in human history. And, if Thomas Kuhn is even one-quarter correct, science is not a matter of objective reason alone.

But the bigger point to be made here is that science depends on faith as much as your average religion. That is to say, it depends on trust.

Yes, of course scientific experiments can be replicated. But chances are pretty good that you didn’t replicate them, and that someone else did it for you. And if you yourself did replicate some experiments, did you repeat the replication in order altogether to avoid having to take someone else’s word for it?

To skip over various levels of this exercise, here’s the end-point it leads to, using chemistry as an example. If you want to know something in chemistry without relying on trust, you will have to begin from the very beginning and repeat all of the experiments that led to the current state of chemical knowledge: all of them, multiple times each. You would die of old age before you caught up with the present state of chemical knowledge. And all of your hard work would be useless unless others had the good sense you lacked and were willing to take your word for it at least some of the time when you said that your experiments had turned out the way they had.

Even for scientists, scientific knowledge relies heavily on trust in testimony: the testimony of other scientists. As for the scientific knowledge of those of us who aren’t scientists, we are left where Scott Adams puts us in the Introduction to this book: depending on the word of people (most of whom we’ve never met) who simply tell us how things are.

Augustine (the real Augustine, the Church Father and founder of medieval philosophy) both here (chapter 5) and here (cartoon version here) is even more helpful than Adams. These are the sort of examples he uses:

- Do you know that Caesar became emperor of Rome about 50 BC? Yes; you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of historians.

- Do you know that Harare, Zimbabwe, exists? Yes. But if you haven’t been there, then you know it by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust–in the testimony of geographers or of people who have been there.

- Do you know who your parents are? You know that also by faith–by pistis, by fides, by trust in what they told you.

(On this last point my students instinctively think of DNA tests, at which point I explain to them that they would need not only to perform the test themselves, but to start from the very beginning of genetic science and reinvent it singlehandedly if the goal is to know who their parents are without taking someone’s word for something.)

The Resurrection of the Messiah: an article of faith

No doubt some readers will suspect that I am attacking the legitimacy of science. Not at all. To the contrary, I presume the legitimacy of science.

I am only pointing out that faith, being trust, is something on which science depends; and, since I am in fact assuming that science is a source of knowledge, other beliefs that rely on reliable testimony can also be knowledge.

What you need to get knowledge by trust is a reliable testimony. And we have plenty of reliable testimony: science, history, geography, and (for most of us) our parents. We live our lives by this testimony.

Thus, the crucial question for religious knowledge is this: Do we have any reliable testimony supporting any religious beliefs?

For example:

- Are there any prophets of Jehovah?

- Are there any holy books? Any books that are God-breathed and inspired?

- Is there a real Messiah who can tell us about God and about how we can know God?

- Are there several predictions about the Messiah made centuries before his birth which all converge on the same person?

- Are there accounts of the Resurrection of the Messiah coming from eyewitnesses of sound mind?

- Is there a Roman Catholic Church with infallible authority, or at least a universal church with reliable authority?

Well, yes. We do have some of these things.

And why should you believe me when I say that? That’s a good question. And, more generally, how do you recognize a reliable testimony in religion?

To ask this question at this point is to observe that I have only showed that knowledge and (religious) faith can be the same thing–not that they ever are. It is a possibility, but that doesn’t mean it is a realized possibility.

But that’s enough ground covered for one opening post. Maybe we can talk about whether this possibility is ever realized, and about how we can know whether it is, in comments, or in a new thread.

Note from the author: We did indeed talk about it comments. See comments #s 156-161 for a handy overview of my thoughts on that subject (and an addendum showed up in comments #s 182-183, and another one in comments #s 262-263).

Published in General

Now about miracles: This might need a new thread. It would at least need its own comments; I can probably give it a shot; but it would be best if you first state the objection against miracles.

Dude what’s your damage? I didn’t do anything to justify being the object of your incessant heckling tonight. I was trying to have an intelligent and entirely civil conversation about something else, something other than what you wanted to talk about. Deal with it. Or go find somebody else who wants to discuss what you want to discuss.

By the way, the dogs are fine thank you. One’s laying here right next to me now. And the place in Michigan is also fine, or at least it was last time I was there a couple of weeks ago. Heading up again this weekend now that it’s warmed up hereabouts. But we’ve got a caretaker there, and some good neighbors. So if there was a problem, I’m sure I’d have heard.

Have a great evening.

Relax Cato. I wasn’t heckling you. I was simply pointing out your flawed theory between religion and science. (I thought that’s what the post was about) You obviously weren’t in the mood for it. I apologize.

Here goes, but this isn’t real sophisticated and it isn’t going to surprise you. I don’t believe in miracles. Full stop.

Now maybe you’ve seen enough from me to know that that doesn’t mean I 100% rule out the possibility. I don’t 100% rule out the possibility that we’re living in a computer simulation either. But rising from the dead is so sui generis that despite some ancient testimony (which itself suffers from multiple hearsay and other credibility problems I believe) I rate the odds of the claim being true somewhere in the range of the odds of dying from a rabid kangaroo bite, or an asteroid strike, or something. Basically, if you’re telling me that someone, 2000 years ago, violated the laws of nature, the standard of proof I’m going to accept is going to be really, really, really high. It probably wouldn’t be too much to say that you couldn’t get me to believe a 2000 year old story to that effect without some really compelling physical evidence at least. The age itself adds mountains of uncertainty to the underlying claim.

By the way, a big part of the reason the age is such a big deal in my evaluation is that falsifiability question again. If it’s claimed to happen today, and a lot of really smart, really skeptical people are permitted to investigate, challenge, experiment and test the truth claim in every way they can think of and can’t falsify it, I’m going to have a lot more trouble dismissing it. Instead it happened in a more credulous age among credulous people of limited ability and inclination to seek to disprove it.

And then it was handed down before being written down.

And then the stories of it were selected by a group of men as canonical, from among a variety of options for Jesus stories.

Approaching the question from an unbiased perspective, we would not presume the the laws of nature are absolute; if God exists, they are His creation, and He can overrule them.

So we must handle the question of miracles empirically and allow experience (including science but also history) to inform us not only what the laws of nature are, but also whether they are ever overruled. If we have enough experience of the world to determine what these laws are and if we also have experience of their being suspended by God, then we do have good evidence for miracles.

So what matters is whether we have really experienced them and have historical knowledge of the experience–whether or not that knowledge is falsifiable or verifiable (and the Resurrection might be verifiable, if this article is correct).

So if the historical testimony for the Resurrection is, say, a bit more reliable than the evidence for the death of Socrates, then we can have knowledge of miracles.

It seems to me that it is indeed the case, and so I accept the Resurrection as a historical fact. I’m with Craig, Craig again, and with Wright (though I admit I haven’t read that book).

Now to look three objections to the historicity of the Resurrection.

Not so. (Lewis would call this “chronological snobbery.”)

The Holy Spirit in His work of inspiring Scripture ensured that we would have records of the suspicious Athenians in Acts 17, as well as the apostles themselves in the Gospels, who believed after seeing and testing. They could believe in a ghost, but had difficulty believing in a bodily Resurrection.

Thomas wouldn’t believe until he could see and touch the very injuries!

As for fact-checking, Paul invites it, pointing to various eyewitnesses including one group of nearly 500 whom the Corinthians could consult.

As for the nearness in time which helps to establish historical reliability, and as for the alleged differences in the available Christian traditions:

Paul says this in a letter we know to be written by Paul. He points to the Resurrection as a historical fact, at the heart of the Gospel, which he had taught the Corinthian believers from the beginning and which he was himself taught before that. He points to it as the consistent teaching of the other Apostles, each of whom had met with the risen Messiah in the flesh. And in Galatians, also known to be written by Paul, he points to the Gospel he teaches as the consistent message of all the leaders of the early church.

And the second is:

I liked this. Yes, we hold so much “sciemtific” knowledge on faith. I’ve never seen a proton or an electron. If suddenly tomorrow the concept of electrons and protons were dispelled I would after a bit of shock take on the new theory on just the same faith as I did the old.

First, just some general thoughts about your links.

The NRO article makes a lot of claims about the Shroud I’ve never seen before, and makes no effort at all to grapple with contrary evidence. This gives it the feel of a piece that started with the conclusion and then constructed the argument. There are shroud debunkers who do the same thing on the other side. But at the end of the day, the shroud is an interesting artifact, and I don’t know enough to take a strong view on its authenticity or lack thereof. If, however, I became convinced that it’s authenticity was likely, that would be the kind of “physical evidence” that I mentioned might overcome the very, very strong presumption against belief in miracles.

I liked the first Craig piece. The thought process he lays out for evaluating truth claims in the gospels seems on track to me. Probably not exhaustive, but on track.

The second piece, however, seems to ignore what to me is obvious. If you’re going to claim a miracle happened the burden, and it is a heavy one, is on you.

There’s a lot I liked in this post, but I think this example misses something important: the point shouldn’t be to confirm everything yourself — that, as you say, would be madness — but to be able to challenge any given point for explanation and reproducibility.

In any empirical enterprise (particularly science), incredulity should be answerable by an experiment; “How do you know that’s true?” should be followed by “Well, this might take a while and/or some money, but here, let me show you.” Philosophy and religion can’t do that, which isn’t to denigrate them.

That last point really goes to the objection I have to the move you make in #36. Unless I reading it wrong, it almost appears that you’re saying that in order to be “objective” we have to start out assuming that compliance with the laws of nature and suspension of them are equally plausible.

Craig himself refers to historical congruence as one of the “signs of credibility” to look to in evaluating historical claims. We live in a context in which we know something about rising from the dead. I, and I suspect you, have lived through a period of millions, perhaps a billion, human deaths. None of those people has risen. That does not prove that it is impossible. Indeed, proving impossibility is notoriously problematic. But it is persuasive enough to cast a pall, a shadow, a absolute solar eclipse of doubt on one ancient claim of a man who rose from the dead.

In the end, this I think will turn out to be really where we differ. You are credulous about this claim. I look at it and see something so categorically at odds with the general human experience that I demand the very strictest proof before I will even consider giving it credence.

I wasn’t implying certainty. Obviously, certainty about anything is impossible. What’s not impossible is overwhelmingly convincing evidence. Many people devote their lives to this search for truth and are completely open to being completely wrong if someone can show that they are. Being able to convince several of these people would be very strong evidence in your favor

Because someone is doing it wrong. Someone is making a logical fallacy or not being a dispassionate truth seeker. It’s impossible to agree to disagree. At least one side is wrong. They are either not agreeing on the assumptions, incorrectly applying logic, or otherwise misunderstanding the data. Someone is being disingenuous, whether they think they are or not. All else being equal, if one party is getting upset, they are more likely (not guaranteed) to be the side being irrational.

Whoa, whoa, whoa… am I reading this right? You’re claiming that if there is slightly more evidence that “someone rose from the dead a long time ago” (something that goes against all contemporary understanding) than “someone died a long time ago” (an inevitability), then you have evidence of miracles?

I think it’s false to claim presuming the laws of nature are absolute is biased, in so far as they have never been shown to not be absolute.

This is why so many people who devote themselves to rationality and Overcoming Bias become consequentialist utilitarians. They assume our intuitions are biases instead of prima facie knowledge.

Presuming the laws of nature are absolute is knowledge, not bias. Unless you show where it is not absolute, and how this inconsistency could plausibly lead to what you want to show, you can’t get off of square one.

If that’s really what you think, why are you here on this site?

You should be a Progressive. The “experts” are overwhelmingly Progressive, and if you ask them, they’ll tell you it’s the only reasonable position to take.

But it has been nice having you on this site! We’ll miss you…

When experts agree on something they are usually right. This is a fact. They should be since they’ve thought about it and studied it way more than other people. This doesn’t mean they are always right, or that calling someone an “expert” makes their opinion more likely to be right, or they are right about political things unrelated to their subject of expertise, but you take expert opinion for granted all the time. I know because it quickly becomes hard to function if you don’t provisionally trust anyone’s opinion about anything.

No, it’s an article of faith, which is not knowledge. There are many current examples of “expert” opinion which is wrong and proven so, but continues to be practiced.

“Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.”

“Science” the institution is in the midst of a reproducibility crisis at the moment. The facts they thought they’ve been generation are not trustworthy.

Yeah, it’s certainly a problem. Most professions would like to clothe themselves in the aura of certainty and deference that attaches to physicists and engineers—and I say that while in the middle of reading a book about how much of modern physics is a fraud.

Much of what these professions do to attain that deference is little different from a confidence game.

So your faith is of great value to the experts, but it’s not backed by knowledge. It’s not a fact.

There’s a difference between individual research papers, of which most are false, and expert consensus opinion vs layman opinion. When they disagree, the experts are usually right. I’ve contributed several things of my own to the likely incorrect literature. And it’s only an “article of faith” in the same sense as when I open my eyes I believe the things I’m seeing are real.

It is a fact that consensus expert opinion is usually right when they disagree with laymen. It may not seem like it for cases like global warming, but even there the consensus opinion isn’t nearly as strong as various media reports like to pretend.

Augustine,

In an extremely technical sense you are correct. However, Kant’s main concern is separating theology from philosophy. Hegel mixes the two using the concept of the Absolute. By doing this Hegel short circuits belief in Freedom and loses everybody’s individuality in a World Spirit. Hegel is far more impressed by Napoleon’s artillery than by Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. Kierkegaard is especially critical of Hegel on this and rightly so. Hegel is also a disaster for theology as he inadvertently drags what should be faith into a very confused system of reason. Marxism is the result. Dialectical reasoning was originally Kant’s term. Kant means false reasoning by dialectical reasoning. When you attempt to answer questions that can’t be answered by reason you wind up in an endless dialogue thus dialectical reasoning. Hegel then Marx make dialectics into a new magical form of reasoning that will produce wonderful results. Dialectical reasoning doesn’t produce wonderful results and is much as Kant first described it. Marxism as we have painfully learned over the last 150 years also doesn’t produce wonderful results but rather merciless horrors.

Regards,

Jim

No one does know much of anything about economics. At least not macroeconomics. As a matter of observation, it is generally true that if you pay people to do something more people will do it, and if you lower the price of something more people will buy it. Beyond that, economics is like philosophy – it never solves anything and economists never agree on anything.

Since much of the OP deals with the concept of “reliable authority,” I think the key point here is to define that term. I would offer the following definition: A “reliable authority” in a given field is someone who has either demonstrated the ability to make accurate predictions, or who has demonstrated the ability to recount events that can then be verified from other independent sources. Which is why (for example) Einstein was a reliable authority about physics, but so-called “climate scientists” are not reliable authorities about climate (even though they call themselves “scientists” (what a joke)).

By either prong of my definition, I am not aware of any “reliable authority” regarding any significant religious questions. Which is why religion is a matter of faith. And that’s a good thing, because faith has a value of its own, different from the value of knowledge.

Was the resurrection meant to be accepted on a basis other than faith? Was it meant to be accepted the way we accept reports of other historical events? If God wanted it that way, Jesus could appear every time someone doubted it, until all believed. And if you are claiming that it should be believed because the historical evidence is in its favor, you are forgetting that a miracle is always, by definition, the least likely explanation for any historical occurrence. For example, would it have been likely for a first century male author who is making up a resurrection story to include the claim that women were the first witnesses of the event? Perhaps not, but it is a more likely explanation than that a miracle actually happened. So the argument from historical reliability sort of misses the point.

Egad. I’ve been elevated to the Main Feed, and I’m already 15 comments behind and I can’t do anything about it till tomorrow morning!

Thanks for the comments, everyone! My thanks to the Editors for the promotion to the Main Feed!

Like I always say in these situations, I imagine I’ll check in in the morning, but I can’t promise to deal with comments as well as they deserve.

Ricochetti are pretty intelligent and civilized anyway. You should be able to do just fine without me.

Augustine,

Thank you for the good post. Talk to you later.

Regards,

Jim

For what it’s worth, I’m looking forward to your responses. We were just getting to the fun part. But if duty calls, I understand.

You simply cannot evade this, Augustine. There is no extraordinary evidence for the things which you (by definition) have faith in, which is why you have faith that they occurred – not evidence.

By your definition, a well-documented claim of alien abduction has similar credibility to the testimonies of the Apostles – indeed, better! The principals involved are frequently still alive and available to be questioned, they have thousands of people who corroborate that they too have had similar experiences and have the advantage of being difficult to disprove.

I just don’t think anybody is being abducted by aliens, just as I don’t think that Jesus came back to life after being beaten and tortured to death and for similar reasons: There’s no evidence that they occurred. It’s fundamentally unbelievable and alien to our species’ experience. That doesn’t mean that I have malice towards the people who believe these things, but the difference in how people who believe the one claim vs. the other are treated is telling.

Alien abductees are considered moonbats, but people who believe that a dead guy came back to life are treated reverentially – to the extent that profession of that faith is a litmus test for high political office. I find it shocking at times.

In terms of the faith in science, this video is a good primer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h2Vx9qoLzFs

It mentions Gödel’s incompleteness theorems.Basically, in any logical set, there are things which are true, but unable to be proven. The example in the video is Euclidean Geometry.

No, there is evidence: the testimony of the witnesses. It’s how you evaluate the evidence, the weight you give it, that may make you disregard it.

Why “overrule” and not “use”?