Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

The Coming Crisis of Immortality?

The Coming Crisis of Immortality?

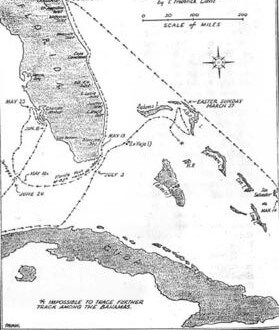

Throughout recorded history, man has dreamt of eternal life. Christian theology promises immortality for the spirit, but not the flesh. Ponce de Leon searched in vain for the Fountain of Youth. Every recorded civilization has its myths of magical elixirs, charms and talismans, mystical islands, and fantastic secret gardens; all said to confer a remedy against age and death — and all, until now, just myths, no more.

Throughout recorded history, man has dreamt of eternal life. Christian theology promises immortality for the spirit, but not the flesh. Ponce de Leon searched in vain for the Fountain of Youth. Every recorded civilization has its myths of magical elixirs, charms and talismans, mystical islands, and fantastic secret gardens; all said to confer a remedy against age and death — and all, until now, just myths, no more.

Some of you may have noticed this article in the Washington Post over the weekend. Apparently, our Tech Titans have decided they’ve had enough of religion and myths. They want immortality, in this lifetime:

[The tech titans] who founded Google, Facebook, eBay, Napster and Netscape are using their billions to rewrite the nation’s science agenda and transform biomedical research. Their objective is to use the tools of technology — the chips, software programs, algorithms and big data they used in creating an information revolution — to understand and upgrade what they consider to be the most complicated piece of machinery in existence: the human body.

The entrepreneurs are driven by a certitude that rebuilding, regenerating and reprogramming patients’ organs, limbs, cells and DNA will enable people to live longer and better. The work they are funding includes hunting for the secrets of living organisms with insanely long lives, engineering microscopic nanobots that can fix your body from the inside out, figuring out how to reprogram the DNA you were born with, and exploring ways to digitize your brain based on the theory that your mind could live long after your body expires.

I should say from the outset that I doubt any of this will work.

But as a thought experiment: What if I’m wrong?

From time immemorial, human society been organized in the certain knowledge that every creature born must die. But what if we succeed in understanding the forces that control senescence and death? What we can understand we can control. And what we can control, we will control.

Religion, politics, love, family, desire, ambition, philosophy, justice, art, literature and the meaning we assign to life itself would be destined to change and change forever.

What if they merely succeed in a more modest goal–an increase in the maximum human life span of, say, 50 percent? This would surely be humanity’s greatest scientific achievement; advances such as the invention of the printing press and the discovery of the atom would seem trivial by comparison. The organizing principle of all human understanding, all striving – to every thing, there is a season – would be upended.

What would it cost? Clearly, the technology will be expensive. Would immortality–or a vastly longer life–be available only to a small minority of the population? Clearly, yes. If, as a society, we cannot pay for everyone–and we cannot–how would the immortals be chosen? Who will live and who will receive a death sentence? Would mortals and near-immortals exist alongside one another? What kinds of conflict would this engender?

What would become of the multitude of healthy, vigorous, but chronologically ancient people who have no established role in society?

Extended life spans would have revolutionary economic effects. Retirement, as we know it, would become meaningless. What would become of the idea of a career or a destiny in life?

What would the world be like when increasing numbers of people live indefinitely, and children must compete with previous generations—generations that refuse to die—for jobs, space, and every other resource?

Would religion be meaningful absent the prospect of death? If men and women can achieve extended or eternal life here on Earth, would the motivation for following the ethical teachings of religion be weakened? What do leading clergy say about the prospect of extended life on earth?

What would it mean to pledge love until death do you part, if death could never do you part? What is the future of marriage, of the ideal of romantic love, of the family, if human life span is unlimited?

How would functional immortality transform our attitudes toward justice—how, for example, will it change our attitude toward the death penalty? Or a sentence of life imprisonment?

What would become of poetry, literature, drama, and painting in a world of infinite youth?

It doesn’t seem to me we can confidently say, “They will never pull this off. It isn’t even worth considering.” Strange things have already happened in my own lifetime.

Perhaps we should ask ourselves these questions?

Published in Culture, General

SciFi authors have been pondering this question for a while now.

The general assumption is that the treatments will be expensive, thereby creating a new, very long-lasting aristocracy…

Nothing that strange has happened in your lifetime or mine. I think there’s zero chance of this happening in my lifetime.

After we cure diabetes, heart disease, and cancer, call me. Maybe then we’ll understand life well enough to seriously consider this a possibility.

Until then? No chance.

“Nothing that strange,” he says, while chatting with me about this in real time …

Putting aside the question of immortality — which I agree is unlikely — and focusing on the prospect of a meaningful increase in life expectancies in the nearish term, e.g. the 50% you mentioned, I have a few thoughts:

1) It simply wouldn’t be so shocking. Reported numbers vary because of methodological differences, but there’s a good case to be made that we had at least a 50% increase in life expectancy in the U.S. in the 20th century.

2) I am not concerned with the cost. If the technology is seen as widely desirable, its costs will likely plummet as mass production for a mass market takes hold.

3) The biggest question is — will it be desirable. If it means an additional 30 or 40 years of dotage and decrepitude, the possibility of its use will raise many questions you haven’t asked and we may both need and want to forgo it, not because of the cost of the technology, but because of the cost of care for the infirm and the limited benefits it provides. But can we do that? We will have to learn. If it means an additional 30 or 40 years of vigor and productivity, I think there’s little doubt it will be adopted, and will be an economic boon.

At least this scenario would require little by way of new literature.

Risk tolerance is inversely proportional to age. So an older society is more careful and much less entrepreneurial.

The world will become increasingly boring. Just as an aging Japan and Europe already aim for security at the cost of liberty, so, too, would aging Google titans.

Humanity would not end up achieving more, just taking longer to do what is already done. Which is not so different from what we see in all the arrested adolescence around us today.

Globally that’s already becoming the case. On average people in the US live almost fifteen years longer than people in India. Ample shelter and nutrition, education and access to better health care will do that.

The choice will be a function of money, the way it is now.

It’s already sort of happening – rich people in India live, on average, more than a decade longer than poor people – but often they live not too far from each other, and in close daily interaction.

What makes it workable despite this in India is the poor having some hope of mobility or improvement. In real life great wealth and opportunity is almost always inherited – but the perceived possibility of improvement (if not in this generation, then the next) maintains some social stability.

My feeling is that it’s when that hope curdles, or becomes risible because of the gap between what people have and what they see and want, that we see the most grotesque spasms of instability and violence.

I suspect that unless we’re talking about extending youth, as well as life, little would change that dramatically. Few would want an extra 30-40 years of senility and decrepitude.

If it were reliably possible to extend youth, however–to give people an extra 30-40 years of health and vigor–we’d have a very different kind of human experience.

People used to be adults at 15. Now, with extended lifespans and great wealth, people grow up at 40.

Accomplishments are like gas: filling the available space without increasing total mass.

Yes, a technology that’s little different, fundamentally, from the telegraph or smoke signals.

Genetics is several orders of magnitude more complicated, at least, and we understand very little of it.

You’re talking about not even playing God—but being God’s Editor. Better than God.

Like I said, little to worry about here.

Average life expectancy.

Life expectancy of a single, healthy, long-lived individual has not changed much in recorded history.

I agree. As I said, I don’t think this will work. But I’m not so confident in that judgment as to say, “No point even wondering.”

Yes, it seems to be about threescore years and ten, give or take a decade. Most of the gains have come from reducing infant and childhood mortality.

Our bodies are only half the equation. Our minds/souls clearly calcify as we age. When we are young, both body and mind are flexible and adventuresome. When we are old? Not so much.

I wonder how much of that is physical. Or how much of it can be attributed to our natural sense of life expectancy.

That is a function of physical limitation. Assuming that one remains equally vigorous then really I think it is as likely that we become more adventuresome. No need to buckle down and start working, after all you have 60 years in which to do that why not take 30 to be a traveling musician and see the world and then come back get a degree and find a job if that whole music thing doesn’t pan out.

After all when you are young and healthy all you have to afford is food and shelter and in a modern economy those two are not that expensive.

I’m glad people have brought up the fact that we have already increased our life expectancy by about 50% at least in the last 100-150 years. The changes were significant, but hardly felt dramatic. They went along with wider changes ini technology and living standards.

I think one thing you will see with increased longevity is an increase in educational attainment by individuals. We already spend more time in school than our ancestors, no reason to think that if we lived to be 150 we wouldn’t all go to get our PhD’s.

My point is more basic: the fact of death makes the living much more driven. Where is the urgency in life, if it extends indefinitely?

Here is how I observe the phenomenon: when people have all day to get a one-hour project done, the project is never finished first thing in the morning. It is quite likely to be finished late at night, with the day spent doing other things.

Lives are like this. People are much, much more motivated to be productive when they have a real deadline. Remove the deadline, and the vast majority of people will simply lose that motivation. Life will be nothing more than long.

The last item of my bucket list is to die young, these guys are gonna need to be successful for me to pull that off. I’m already past 3 score.

I’d say the changes have been tremendous, so great that people alive today are almost invariably unable to comprehend what life was like when many children died. As well, living with pain almost as a given, almost without relief. Family structure changed a lot over the last two centuries, because of modern science. Democracy became far more democratic, too.

As for a future with longer lives, everyone who wants to make it past the century mark will have to live in a far more calculated way, being far more aware of & adverse to risk. A big change lies that way, too.

As with most technological advances, I’m sure it will cause tremendous problems for many people.

But as for me, I’ll sign up for at least a hyper-extended life, if not immortality.

I really like it here.

Oh, indeed. In fact, I’ve had a notion for a scifi book in my head for a while that revolves around the implementation and consequences of immortality.

I think, based on what we currently know about the genetics, that immortal humans would be a different species. Their genome would be so different from ours that we wouldn’t be able to breed with them.

We’d have engineered our replacements, in other words.

I think this outcome is more likely than an AI takeover of the world…

It always cracks me up when people say risible claptrap like this.

Yes, agreed. I’ve learned from some older friends that being old is as much a question of attitude as of biology.

Realizing that getting old can mean life gets better with increased wisdom as opposed to getting worse has made it much easier!

We’ve also learned that a lot of the physical degeneration that supposedly results from aging is in fact the result of increased sedentism*, not age.

If you act young, your body can stay much younger than someone who gives up and sits on the Couch of Doom.

* [Yes, that’s a word, I checked!]

On the other hand, risk tolerance increases with increased trust in the future’s ability to reward us for our efforts.

This trend is evident not only across differing demographic groups, but also within ourselves: when the rest of our future cannot be trusted, why take on additional risk? Physical frailty certainly does a number on one’s ability to trust in the future. Having less life left may do the same thing: if you won’t be around, how can you ensure that contingencies are handled effectively? People who live longer, healthier lives at least have the opportunity to take on longer-term projects.

Likewise, where is the urgency if life could end at any time? Now, that might sound strange, since people who do find out they have only a few months to live often go on a whirlwind tour to enjoy all the stuff they never got around to enjoying before. But they feel little urgency to begin long-term projects with payoffs extending far into the future – and no wonder!

I think your point about real deadlines is right on. And real deadlines are predictable – they happen more or less when they say they will happen, neither being pushed arbitrarily back nor arbitrarily forward.

As I’ve written before, I know for a fact having survived a bone tumor at 15 and having had my birth mother die of cancer materially affects my already naturally dour outlook—in bizarrely conflicting ways, probably also due to the touch of depression that led to my birth brother’s suicide.

Come to think of it, a gene therapy for mental illness alone would be huge.

Let’s see. Manufacturers will have to rejigger those “lifetime warranties.” Those guys flogging reverse mortgages are going to get it in the neck. It will play hell with copyright duration.

On the other hand, will Hollywood inflict as many remakes on us if the audience really has seen it all before?

“Gödel’s Ghost

“It always cracks me up when people say risible claptrap like this.”

Oh come on. You’re generally a bright fellow on this site. You can do a bit better than that.

Sadly, the notion that the internet isn’t fundamentally different from the telegraph isn’t a new one, and it’s not my idea:

Speed has increased, but the basic function is the same: sending dots and dashes.

Gödel’s Ghost

Why is it risible claptrap to point out that near-instantaneous communication over a distance is a common technological advance between smoke signals and the internet? The difference is bandwidth and fidelity.

Think of this from the perspective of a Cubs fan …

To get back to the main point:

We’re already immortal, at least assuming we get over the suicidalism that’s threatening to end western civilization. We should assume homo sapiens sapiens—or whatever evolves from us—will be around for the indefinite future. Unfortunately, neither earth nor our sun will be. So we have to get off this rock eventually—we literally have no choice.

Thankfully, this is getting easier to do. In particular, it won’t be long before we can create von Neumann probes that you could hold in the palm of your hand, but are capable of interstellar colonization by carrying the DNA for an entire human colony, the computing power necessary to build and maintain the colony, and by scavenging the material resources needed from the environment in situ.

NB: by “won’t be long” I mean in geological or cosmological time. If it takes a couple of hundred years (it won’t, but for argument’s sake) that’s obviously the blink of an eye. If it takes a couple of millennia, ditto.

So here-and-now physical immortality would “just” accelerate the pressure that already exists, unless you’re tacitly assuming the eventual extinction of homo sapiens sapiens and our descendants. That’s not a bet I’m prepared to make.

Exercise for the reader: situate these comments in the context of The Collapse of Complex Societies.

I have fond memories of this poem… if “fond” is the right word…

Everyone in my family fears having outlived their usefulness. Of course we all most likely will, to some extent. But hopefully not for long.