Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Iraq: What Might Have Been

Iraq: What Might Have Been

In a previous thread, Ricochet member Majestyk expressed a major complaint that he has about libertarians, liberals and even conservatives who gripe about the Iraq and Afghanistan wars: What is your alternate scenario?

In a previous thread, Ricochet member Majestyk expressed a major complaint that he has about libertarians, liberals and even conservatives who gripe about the Iraq and Afghanistan wars: What is your alternate scenario?

If we could unwind the clock of history and place you inside George W. Bush’s head (a la Being John Malkovich) what is your preferred policy prescription for U.S. foreign policy in the days following 9/11?

I never hear that question answered and I barely hear it asked.

So, okay, I’ll give you my answer, and then see what you all think:

I am going to assume, for the purposes of this discussion, that we all agree Saddam Hussein was an outstandingly brutal dictator in a region that pretty much specializes in brutal dictators. He was a problem for his people, for his neighbors, and for the United States and our allies that would, eventually, need to be solved.

The key word there is ‘eventually.’ Since Saddam was not, in fact, responsible for 9/11, and did not present an immediate threat to us thanks to containment and sanctions, he need not have been anywhere near the top of the list of the nation’s priorities in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks. Had I been inside George W. Bush’s head, I would have been chanting “Afghanistan….Afghanistan… Afghanistan…”

Once the echo of my chanting died away (‘…ghanistan….istan….nnn”), I’d have recommended a swift, violent, targeted, and punitive attack on Afghanistan, with the goal of taking out Osama bin Laden and/or as many members of Al Qaeda and the Taliban as possible while making it look easy.

When we were finished, if whomever remained in the way of Afghan leadership expressed a desire for help build a reasonable, decent country, we would join a broad coalition of other nations ready to help them do it. If they preferred to be a crummy, impoverished, savage backwater, so be it. Just don’t screw with us again.

What about Iraq?

For all their undoubted sufferings, there were advantages for the Iraqi people in being oppressed by Saddam Hussein.

First, he wasn’t an Islamist. He was barely a Muslim, one of several reasons why Osama bin Laden loathed him. (After the invasion of Kuwait, Osama proposed having his people push the Iraqis out, and was furious when the Saudis allowed the U.S. to do it instead, especially since this meant placing U.S. bases on sacred Saudi soil).

Saddam was a secular butcher. His heroes were Hitler and Stalin, so women in Iraq not only did not have to wear a hijab or hide in their homes, they were educated and employed. If they were targeted by the regime, it was for their politics, not their gender.

Second, Saddam was big on education. When he came to power, the vast majority of Iraqis were illiterate. When he left office (so to speak) the situation was reversed: the majority could read and write. Saddam wanted his country to be modern the way Hitler wanted Germany to be modern, so he invested in training and technology in a way that an Islamist state never would.

By educating his people and neglecting to oppress women, Saddam was creating the very class of people most likely to identify with Western, secular democracies, to increasingly resent being terrorized and oppressed, and to have the ability to organize his overthrow and manage the aftermath. I think it likely that, within a few years, Iraqis might well have created for themselves the very system that George W. Bush tried to impose by the worst of all possible means: an ineffectual bloodbath.

Tragically (in retrospect), we invaded. We trashed the infrastructure and sacked the police and army without providing alternative sources of law and order. The chaos inspired a massive, panicked brain-drain of the elites, and created a baleful association between the words “democracy” and “imperialism” in the minds of the Arab masses. Had we postponed dealing aggressively with Saddam, not only might we have spared thousands of American and Iraqi lives, but the Arab Spring might have bloomed a decade earlier in cleaner, richer soil.

The United States would have emerged from the post-9/11 period with undiminished moral capital, as well as the energy and will for further and more crucial armed interventions, both of which would give the president — any president —-a far stronger position from which to negotiate with other potentially problematic or threatening countries.

Published in Foreign Policy, General

Alright. You have managed to get me to come out of my self-imposed exile.

When I asked that question I was laying a very careful trap. You’ve sprung it. My general complaint about Libertarian intransigence about foreign intervention has much to do with Libertarianism’s (and the Libertarians who believe in it) appearance of having an episodic rather than continuous understanding of history. By that I mean that it seems as if Libertarians view history as a practically unrelated series of incidents which have no connection to the past or consequence upon the future.

In this case, the episode we are talking about is the Iraq invasion of 2003. The issue is that this is not an isolated incident in the history of the world; a single data point which stands by itself and has no other implications.

The 2003 Invasion of Iraq is better understood as a continuation of hostilities which were initiated with Operation Desert Storm. Although relatively unreported by the media (there was some chatter about it around the time that MonicaGate was happening) there still essentially a hot war being fought in the skies of Iraq for years after the Cease-fire, as Coalition Aircraft patrolling the No-Fly Zone in Iraq were repeatedly shot at with surface-to-air missiles and anti-aircraft artillery.

Add to this the various other depredations which J-of-E has mentioned and you have a compelling argument that sufficient violations of the ceasefire agreement were committed by Saddam that the original coalition from Desert Storm should have completed the task which GHW Bush left undone in 1990.

If the international order is to mean anything and the rule of law is to have any teeth, the only body capable of truly enforcing that is the US military. Despite the fact that the Administration foolishly put as the centerpiece of their argument the WMD business, there were a plethora of other reasons cited in the AUMF which had nothing to do with WMD but had much to do with defending the international order; grievances which were wholly legitimate in my mind as a justification for a punitive expedition and/or invasion.

The fact that the Administration bungled the aftermath of the conflict has nothing to do with the rightness or wrongness of the initial action. An entire string of items were mishandled from the size of the invading force, to the disbanding of the Iraqi military and police forces to “De-Baathification”… the list goes on. Under the heading of “broken clocks being right twice per day” you even could make the argument that VP Biden may have had it correct that the state of Iraq should have been partitioned into 3 autonomous regions rather than the insistence upon shackling the politics of the post-war Iraq to the golem of post WWI, arbitrarily drawn geographic lines.

The topic of Afghanistan is also thorny, and the issue is that we have seriously misunderstood the depths of tribal loyalties and the economic structure of life there. That’s another topic that I’m still thinking about.

Weellllll…

I can agree that whether or not an administration bungles a war does not automatically mean that observers are justified in declaring the war morally, legally, an/or strategically unjustified after the fact.

However…

I would not agree that simply because one believes that a war is morally, legally, and/or strategically justified that it also means that one must therefore support the war even when one has no confidence in the administration’s ability to carry it out successfully.

“Rightness or wrongness” is as much about practical outcomes as it is about moral, legal, and/or strategic justification.

Perhaps a better strategy would have been to not invade Iraq and instead do what we could to encourage further Iraq-Iran conflict in the hope of keeping them both preoccupied. It worked in the 80s.

I supported the Afghan action and still would but our mistake was staying around and trying to nation build as opposed to just disrupting Al Qaeda. The Powell doctrine was “you break it, you fix it” but my doctrine is based on the reality we are much better at breaking than fixing so it’s “I break it, you fix it if you want” . I’d rather have to go back and break some more things every few years than to stay and fix it.

I’m not sure I’d be quick to support encouraging conflict, but I do feel that defending one’s actual allies should probably be given a higher priority than preventing conflict between (or within) countries which are not already one’s allies (or trying to create new allies by force).

If a country wants the protection of the United States military, then that country should negotiate a treaty with the US first (or, better yet, apply for US statehood).

“It seems he’s indicated he would be prepared to go into exile if he’s allowed to take $1billion and all the information he wants about weapons of mass destruction.”

This doesn’t seem accurate.

The intent behind all the secrecy and game playing over his weapons programs was to maintain the fiction he had fooled the world. He created a Potemkin vista of NBC capabilities.

If memory serves, Idi Amin was invited by the Saudis. I don’t recall if anyone actually expressed an interest in hosting Saddam. Plus, I think Saddam had skated through enough close calls he probably believed he was the ultimate survivor.

Kate,

I find your point of view false. The simple answer is that after “Shock and Awe” we should have gone to the “Surge” immediately. The surge is not just a military strategy. It is political. Instead of Nation building for democracy one simply puts the strongest man who will stay loyal to us in charge. You retain a local strike force and if your man gets into trouble you move in and quickly destroy the trouble. You may be required to reapply the strike force a number of times before trouble gets the idea to go elsewhere to cause trouble.

This is a very simple time tested approach. If we had not allowed our egos to get in the way and assume we could manufacture a solution to all their problems all at once we would have been OK. The Obama attitude of total withdrawal from all foreign policy responsibility and the degrading of the US military is as ridiculous as every other isolationist strategy. An Ostrich has better fore-site than the Obama administration. They are so bound up in their hallucinatory narrative that Kerry didn’t notice that Putin was lying to him. Obama’s ultimate exit strategy is to get out of office before the total disaster that his criminally incompetent foreign policy will inevitably bring.

As always Obama is about blamesmanship not statesmanship.

Regards,

Jim

But then it stopped working. Both countries were escalating beyond simply conventional capabilities. Neither would be friendly if they suddenly found themselves the victorious regional superpower.

But this wasn’t the usual clash of nations. This wasn’t Japanese people supporting their emperor. There were factions and oppression. To me there is a moral component: we damn well are obligated to sort out who we’re bombing and why before we start bombing.

Aside from the moral component there is a strategic one. Breaking things every 10-20 years doesn’t get us anywhere. Holding our noses to support our monster in the region didn’t get us anywhere. Why not try for a more permannt fix? That meant, at the very least, recognizing that there were morally acceptable parties to work with, that leaving shambles might be counterproductive, that smash and dash might not save us blood or treasure in the long run, that helping to birth non-oppressed nations in the region might bring moral clarity (similar to what we had warring with Japan) at worst or downright friendly footholds from which to project stability onto the rest of the regions or maybe even an outright ally in addition to Israel.

We all know about the oil, but the map is such that had we kept up involvement in both Iraq and Afghanistan, we would have had forces directly surrounding Iran, butting up against Syria and Pakistan, and on the radar of Russia. In the event of future necessity, we wouldn’t have had to struggle with the logistics because we would have been on the spot already.

Well, yeah. Saddam took over a country that was better off in many ways before he started to dismantle and destroy it.

Oh, wait, you mean “Saddam had some unfortunate events occurring to him in 1990 that made his job harder and then there was a continuing series of bad luck through the 1990s?”

[I made a mistake about Zafar’s position; worse, it was an uncharitable mistake and I have deleted it here.]. Saddam could have avoided the Gulf War by simply leaving Kuwait. The day before war was declared, Saddam had no excuses that he believed that the West and the Arab coalition wasn’t serious about this stuff; amassing vast armies in the desert ain’t cheap. In both invasions, Saddam’s decision to keep playing tough diplomatically was a truly terrible idea that cost him and his country dearly, and was a choice that falls 100% on his shoulders.

Every time he decided to choose between having a threat to his authority existing and mass murder, the choice to go with mass murder (which was, so far as I know, the option picked every single time), that was Saddam’s call.

No, Egypt didn’t, but Egypt was better prepared to transition with the example of other countries that had democratized, from Morocco (which went pretty far) through to Saudi (which held municipal elections as a capacity building measure for further elections, and to reduce the theological opposition to elections). There’s a lot of small measures, but the rate is faster after 2003 than before.

Like in A Bronx Tale, the people need to see you to remember to respect and fear you. Absence invites mischief.

I find your point of view false. The simple answer is that after “Shock and Awe” we should have gone to the “Surge” immediately. The surge is not just a military strategy. It is political. Instead of Nation building for democracy one simply puts the strongest man who will stay loyal to us in charge.

Hey, Jim! Which point of view?

If we’re talking about what happened after the decision was made to invade, then you and I are probably in agreement:”shock and awe followed by surge” probably sums it up as well as anything.

Humbly, I offer couple of extra thoughts along the lines of “lessons learned”:

if you are going to take control of a country, take control of it. Order and safety are the prerequisite if anything good is going to follow. If you don’t impose order and safety on the ground ASAP, fear will drive the ordinary person to turn to any group, gang or militia who offers to keep them and their children safe. Once people start killing each other and revenge becomes a dominant motivation for action, it will be very difficult to prevent the situation from spiraling out of control.

For odd reasons I won’t bore you with, most of my study of this subject has centered on Abu Ghraib. Detainee operations is not considered the sexiest MOS, and running prisons is among the many unglamorous jobs Big Army tends to devolve onto the National Guard. (Remember the hapless Janet Karpinski?) Knowing what I know now, I would advise the president to make it clear he expects the military to be able to detain, interview and house prisoners under impeccable, state-of-the-art sanitary and humane conditions.

Why? Because the United States was not invading Switzerland. Indeed, for the foreseeable future will be always be invading countries that are disgusting, brutal dictatorships. These tend to be known for the horrors of their prisons. Any war results in prisoners, some of them innocent sweep-ups. How the U.S. treats the people it takes into custody will naturally be closely observed, and will have tremendous propaganda value that, if we don’t make it work for us will definitely work against us.

Another reason that smash and dash might have been counterproductive: a vacuum cries out to be filled. Who were the candidates to fill the vacuum in either Iraq or Afghanistan?

Fascinating post and comments. I was on balance against the war, but could not stomach being lumped in with the 85% of the opposition that opposed the war for all the wrong reasons. I’d like to throw out a few comments inspired by different commenters.

The idea that sanctions were not collapsing is wishful thinking by leftists and libertarians; 500,000 children were starving – Madeline Albright was excoriated for saying that’s a price we should be willing to pay. The French, our most perfidious “ally,” were doing everything in their power to make America the bad guy and make Iraq’s sanctions as worthless as Cuba’s.

Saddam, more than any other dictator in modern times, did seem to have a “das fuhrer” complex. He had already killed over a million people in two wars of aggression and was convinced he was put on earth to redraw borders in blood. I am confident every life lost fighting him when we did saved 20, and every dollar spent saved 10,000.

Saddam was running “Dr. Germ’s” research labs on $20/barrel oil, what mischief could he have accomplished with $150/barrel oil after sanctions had collapsed in a year and he was the Arab lion that had humiliated the US.

What if we had elected John McCain instead of GWB – the most unsuited war leader since Kaiser Willhelm II – and had gone in with 450,000 troops for 9 months, then 100,000 for three more years, then cut back to a 40,000 level for a few more years instead of 120,000 troops for 10 years.

If Rumsfeld really said “I’ll fire the next man that mentions post war planning” he should have been impeached. If Bush knew about that statement and didn’t fire him he should have been impeached.

I agree with your comment on making distinctions which I why I think our Afghan strategy utilizing special forces and airpower in conjunction local allies was the right one as opposed to random violence. My disagreement is with the strategy to stay around and try to reconstruct these societies which is a futile and naive approach.

The idea that we would have forces in perpetuity in Iraq and Afghan is simply unrealistic. If that is what the Bush Administration thought then they were simply crazy. This was not Western Europe or S Korea where we had forces for decades who were not under constant attack from the local populace. Our history shows that our patience for sticking around in these types of circumstances is very limited and our recent history tells us that we seriously overestimated our ability to change these societies. If we stayed in Iraq until 2020, instead of 2010 it would merely have reverted to its dismal state ten years later. That’s why breaking things is the only feasible strategy in this part of the world.

The Japan analogy (and Germany, for that matter) does not apply here. In those cases (1) we destroyed those societies and their infrastructures completely with disregard for the distinction between civilian and military, (2) those devastated societies were left isolated and no one was going to continue to supply them with moral, religious or material support – were the Japanese going to get aid from sympathizers in Korea and China? If they didn’t like us, what were their alternatives – the Russians?

So you agree that the US using force to impose its will on other countries is akin to organized crime?

Why would local allies support us if they knew we were going to be gone in a year or two? Didn’t we see that very dynamic at work?

No. I think that’s a broadly applicable principle.

For what it’s worth, I’m a libertarian who thinks that both the Afghan and Iraq wars were the right thing to do (though hindsight leads to the conclusion that the execution of both could have been better).

Afghanistan’s different.

Afghanistan was really in a state of civil war in 2001. The US did not go in to Afghanistan to eliminate all the warlords. It went in to eliminate one faction, the Taliban, because that faction was harbouring an organization, Al-Qaeda, that had attacked the United States homeland.

The power vacuum created by the removal of the Taliban was much smaller and easier to fill than the power vacuum created by the removal of Saddam Hussein.

Having forces in place, without being under constant attack from the local populace wasn’t unrealistic assuming that we restored order, allowed the people to govern themselves as they wanted to be governed, worked to establish a solid relationship rather than imposing our values, and didn’t constantly signal our desire to leave before the job was finished. As I say, worst case is moral clarity when they reject us whole cloth and become an enemy. Best case is an ally. Anywhere in between would have been acceptable and strategically advantageous.

I’d agree if we were talking about contexts where one has a legitimate claim to authority over the people. That’s pretty clearly not the case when it comes to organized crime in the Bronx, and certainly arguable when it comes to US military action in Iraq.

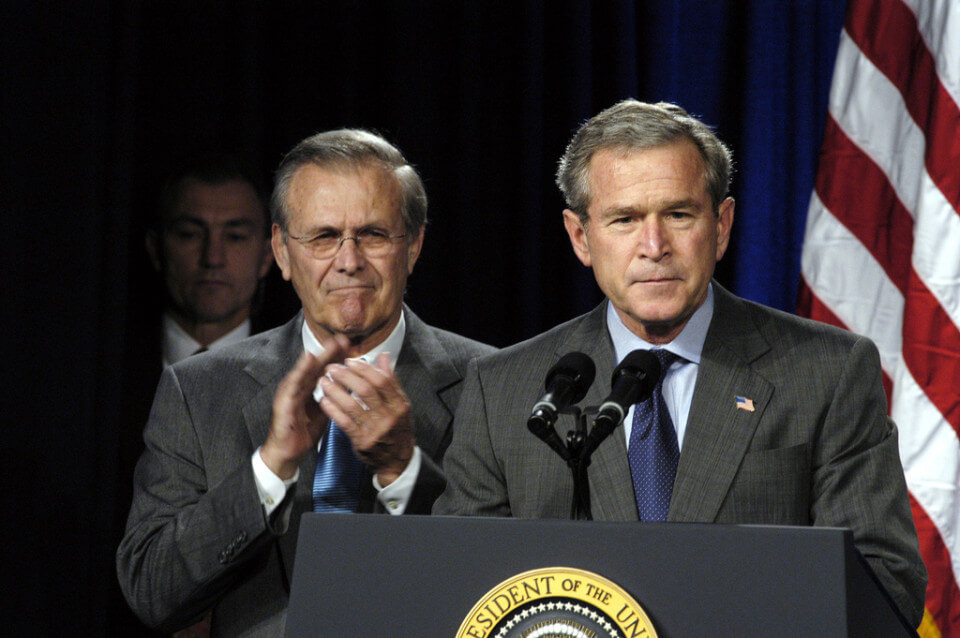

Thanks to someone for putting a picture with the OP! And I’m finding the comments fascinating, too—and enlightening.

The two must be measured separately.

Clearly, the Bush Administration misunderstood or was overwhelmed by the aftermath of the Iraq invasion. Whether that is due to simple naivete, incompetence or malice is irrelevant. Re-litigating the run up to the war is pointless, because the case for war with Iraq was quite solid. The issue is that people who criticize the war want to immediately point at the aftermath of the war and bellyache that it didn’t go as the Administration said it would and use that as a justification for prior restraint.

I wonder if those same people are in favor of our continuing presence in places like Japan or Germany, or if they consider those very costly (in lives and money) engagements to have been worth it.

Then, ironically, after we had actually done the hard work of trying to un-break the Pottery Barn… we abandon the place. That is the most contemptible, evil and stupid thing that we did – and that gets little or no attention, other than the ancillary fact that we get to watch heads get hacked off at the hands of ISIS on the evening news every night.

Right, I agree they’re not analogous examples. It would have been far more difficult, costly, and time consuming to achieve complete destruction and then rebuild them. That’s not what we did in either Afghanistan or Iraq. In both cases it seems that we had a society being unwillingly ruled. I would think it a reasonable proposition that restoring these societies to their own will would have had teh potential for much more benefit than merely eliminating whatever factions we detested and then leaving these other groups to clean up.

I’m not arguing that the US had any claim to authority in the region. However, authority isn’t the only context where either respect or fear come in handy.

The US has had forces in Germany, Japan, and South Korean for over six decades.

Maintaining a military presence over the long-term is a prerequisite for successful regime change.

If a country isn’t willing to invest the resources then do not pretend that regime change is the goal.

Encouraging democracy was the Bush strategy, which seems to be now frowned upon. I agree we can try to not repeat our mistakes, but I think the question to be asked what were our mistakes exactly? Was it invading in the first place, or not invading enough? I have heard it argued that Iraq II was really an attempt to correct the mistake of Iraq I which was leaving Saddam in charge after we beat him then.

Really I think if one looks back all of history is a mistake, or at least it can be argued so. I think our biggest mistake is ever thinking that there is an end to evil. We deal with the evil we have in front of us and when we do we should be brace ourselves for the evil that will arise to take its place.

Even when we will have relegated ISIS and Al Queda to the ash heap of history something new will come up filling in the void and taking advantage of the circumstances presented at the time. I don’t know what that will be, but we shouldn’t think that there is away to defeat these guys without creating other problems down the road.

Imposing one’s authority is the only context where respect and/or fear are necessary.

If the authority being imposed is illegitimate, that pretty much by definition makes it criminal.

Majestyk, I don’t think I’ve ever agreed with you more than I agree with this above. The bitch of all this is that we had already done the hard work and then we simply discarded the whole thing because it wasn’t blooming as quickly as we would have liked or because some of us wanted to vindicate our original opposition despite the costs being unrecoverable and the potential benefits about to come due.

I wasn’t arguing for the US to impose authority.