Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

“Middle Class Economics” — What is its History? What is its Future?

“Middle Class Economics” — What is its History? What is its Future?

In last week’s State of the Union address, President Obama invoked “middle class economics,” his term for his policies which, he suggested, have helped Americans achieve and maintain middle range incomes. But does his agenda represent true “middle class economics”, and if not, what would?

As with many, perhaps most, Americans, when I heard the words “middle class economics,” I thought not about my own history but my family’s. My great-grandfather arrived here with his parents and siblings shortly after the Civil War. There is no record of him having much schooling, but the family clearly coveted education. Records show that his sister, who became a teacher, was soon in college, almost unheard of for a girl in the mid-19th Century. His father was listed in the census as a laborer, but within the decade the son was partner in a store and later either took over the business or started his own, the records aren’t clear. After graduating from college (the family’s first male recorded as having done so), his son married a teacher and took over the business.

With the exception of the women achieving advanced education before the men, this family story has been repeated millions of times on these shore and, more recently, around the world. It reflects a recurring theme, the role of education and entrepreneurship in American and now global middle-class economics. How was this history reflected in the president’s address?

Yes, Mr. Obama promised free community college to all. But the pledge had little to do with real middle class economics. Cost is not the key barrier to completing a program of higher education at either the two-year or four-year levels. The key barrier is the quality of high school preparation.

As reported by the Community College Research Center at Columbia University: “In a sample of over 150,000 students in community colleges… 2.5 percent for students referred to developmental education” (that is, who had inadequate high school preparation) earned a bachelors degree in five years. It is not an exact comparison, but after six years more than half of all students who enroll in community colleges receive a two- or four-year degree or are still enrolled and working on it.

Can remedial work make up for poor high schooling? Surely it can, but according to the Center, “A number of recent studies on remediation have found mixed to negative results for students who enroll in remedial courses.” In other words, the odds are stacked heavily against those who arrive at either two- or four-year institutions without sufficient high school training.

So an administration that is dedicated to true “middle class economics” and value of college will do everything it can to help students secure the best high school education possible, including, maybe particularly, by helping them escape failing or mediocre schools. But again and again, the administration has shown indifference or hostility to school choice in all forms. It has turned its back on Middle Class Economics, preferring what might be called Teachers Union Economics.

How about entrepreneurship? As Ricochet’s and the American Enterprise Institute’s James Pethokoukis has shown, since the recession began, the number of firms closing has exceeded the number starting. It is true that the gap, which for decades favored startups, began to tighten right after Ronald Reagan left office. My guess is that this change had to do with the surge in national business regulation and class action litigation that got going about that time. Still, a disturbing development for “middle class economics” became really bad during the Obama years. In the last six years federal regulation of business has become vastly more onerous and capricious, the litigation culture has been barely checked, and taxes on entrepreneurial income have spiked. Are these examples of effective “middle class economics?”

One more thing. Vast increases in productivity made possible the rise of the middle class in the British Isles and North America beginning between the late 18th and mid-19th centuries. This burgeoning of output per worked hour was a product of institutional and technological revolutions, among them the harnessing of fossil fuels. Surely anyone who cherishes “middle class economics” will take great care in approaching the Chicken Little sky-is-falling claims swirling like a superstorm around climate policy.

Instead the President and his team have brushed aside the large and rapidly growing body of evidence that climate change alarmist have been, well, alarmist. No one is better on these questions than celebrated science writer Matt Ridley, author of the brilliant best seller, The Rational Optimist. One of Ridley’s recent blog postings goes directly to the question of alarmism and middle class economics. Ridley writes:

I am especially unimpressed by the claim that a prediction of rapid and dangerous warming is ‘settled science’, as firm as evolution or gravity. How could it be? It is a prediction. No prediction, let alone in a multi-causal, chaotic and poorly understood system like the global climate, should ever be treated as gospel…. The policies being proposed to combat climate change, far from being a modest insurance policy, are proving ineffective, expensive, harmful to poor people and actually bad for the environment: we are tearing down rainforests to grow biofuels and ripping up peat bogs to install windmills that still need fossil-fuel back-up. These policies are failing to buy any comfort for our wealthy grandchildren and are doing so on the backs of today’s poor.”

Today’s poor are tomorrow’s entrants to “middle class economics,” unless, as Ridley suggests, we precipitously knock out the legs from under the middle class’s energy and productivity stool. This is exactly what the administration seems set on doing in its now-failing (thanks to fracking) war on fossil fuels of all varieties.

The president talked about “middle class economics” for something like an hour. But when all was said and done, did he utter a single word about true “middle class economics”?

And if not, in this time in which we are told middle income Americans are struggling and the ranks shrinking, what would true “middle class economics” look like?

Published in General

I address some of this in my post Powering Down…in which I excerpt a passage from the Fabian socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb:

The manual-working population of the cities was, in fact, mainly composed of laborers who were lifelong hewers of wood and drawers of water whilst that of the vast stretches of farmland and forest outside the cities was as devoid of art as of letters. And the proportion of merely mechanical work in the world s production has, taken as a whole, lessened, not increased. What a multitude of laborers quarried the stones, dragged and carried the stones and lifted the stones of the cathedral walls on which half a dozen skilled and artistic masons carved gargoyles? From the building of the Pyramids down to the present day, the proportion of the world’s work of the nature of mere physical digging, pushing, carrying, lifting* and hammering, by the exertion of muscular force, has almost continuously diminished…. And it must not be forgotten that, in “Western civilization to-day, the actual numbers of men and women engaged in daily work of distinctly intellectual character, which is thus not necessarily devoid of art, are positively greater than at any previous time. There are, of course, many more such workers of superior education, artistic capacity, and interesting daily tasks in Henry Ford’s factories at Detroit than there were in the whole city of Detroit fifty years ago! Along side of these successors of the equally exceptional skilled handicraftsmen of the Middle Ages there has come to be a vast multitude of other workers with less interesting tasks, who could not other wise have come into existence, and who represent the laborers of the cities and the semi-servile rural population of past times, and who certainly would not themselves dream of wishing to revert to the conditions of those times. It may be granted, that, in much of their daily tasks (as has always been the case) the workers of to-day can find no joy, and take the very minimum of interest. But there is one all important difference in their lot. Unlike their predecessors, these men spend only half their waking hours at the task by which they gain their bread. In the other half of their day they are, for the first time in history, free (and, in great measure, able) to give themselves to other interests, which in an ever- increasing proportion of cases lead to an intellectual development heretofore unknown among the typical manual workers. It is, in fact, arguable that it is among the lower half of the manual workers of Western civilization rather than among the upper half, that there has been the greatest relative advance during the past couple of centuries. It is, indeed, to the so-called unskilled workers of London and Berlin and Paris, badly off in many respects as they still are and notably to their wives and children that the Machine Age has incidentally brought the greatest advance in freedom and in civilization.

Quite different from today’s “progressives,” no?

A more important question is…what is this “middle class”?

The “middle class” is political “dog whistle” for “whomever I can convince to vote for me by promising them goodies”. Of course, the Dems and the Republicans do this, constantly. So in more general terms, it’s just populism.

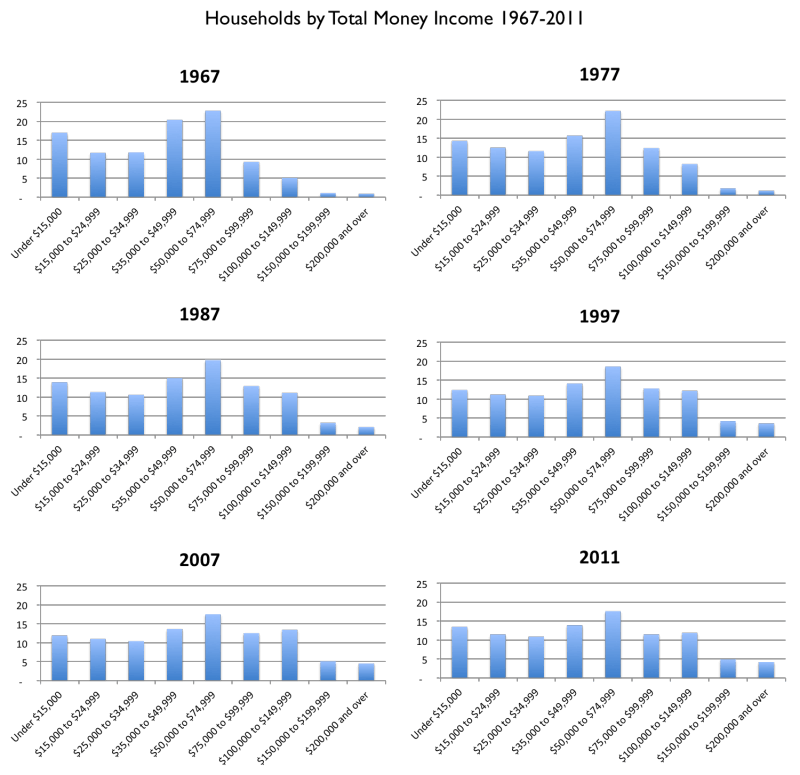

Now, if we look at the numbers:

We see that in previous decades the US population was much more heavily concentrated in the “poor” end and in the “middle”, with very few in the “top”.

We’ve seen over decades the distribution become much more flat and broad. Far fewer people in the bottom, far fewer people in the middle, and far more in the top.

Meaning, people are moving…up…the income distribution.

So why is the “middle class” so important? Why is the “demise” of the middle class so important? Why should we be “helping” the middle class? People have been moving up the income distribution over the last few decades. And that’s what we would want.

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2014/04/mobility-in-and-out-of-the-top-one-percent.html

So then what’s this “middle class” thing, anyway?

Votes.

Most people’s goal is economic security. There are three paths to economic security:

1) Capital: This doesn’t necessarily mean that one has accumulated lots of money. It could mean that you have accumulated lots of human capital by getting a college degree or graduate degree in an in demand field. Or you were lucky and started off with high physical (rich parents) or human capital (naturally talented). Very few people once they have accumulated sufficient capital fall all the way down to the bottom of the economic ladder. This was generally known as the “white collar” route.

2) Work: This is the original “blue collar” model. Work hard, build your skills, join a union that provides health and pension benefits. Generally, the better jobs were in the trades or in manufacturing.

3) Welfare: Learn to live with less. Let the government handle the necessities, and work some under the table for spending cash. Lot’s of free time, but not much to do with it.

The problem I see is that the second path has in the past couple decades become less viable and less stable, which makes people in path 2) feel economically insecure.

As to AIG’s point. People have been moving out of 2) into 1) and 3). Unfortunately, too many people (of all political persuasions) think that anyone can achieve path 1). This is just not true.

The strength of America has always been the large numbers of its middle class using the basic simple definition of class:

Poor-no assets, income less than subsistence

Lower Class- no assets, has income at or slightly above subsistence

Middle class: has income, building assets

Upper class: assets sufficient for living plus accumulation of more assets.

The key to a successful middle class was acquisition of useful skills and networks of useful people.

US Government programs have funneled most policy to protect the assets of the campaign donors and crony capitalists and stood by while the public education system which the middle class depended upon deteriorated in favor of union protection and throwing huge public pension funds to wall street, and then increased the cost of local government capital projects with Davis Bacon and other federal regulations. The straw that broke the camels back for the middle class was the upper class insistence on higher energy prices so they could profit from rigged markets in renewable energy and skim off cap & trade exchanges.

Middle class economics needs to focus on the ability of lower class Americans to have enough left from their paychecks so they can start to build assets and enter the middle class. That means schools that work to avoid the cost of private education or replacing public education taxes with private vouchers and $20-30 a barrel for domestic oil. Drop energy cost and watch disposable income skyrocket. Encourage state governments “encourage” all businesses to hire on skills rather than degrees, which would shift education from one size fits all four year degrees to flexible skill mastery certificates, lowering the cost of entry to the middle class.by the lower class.

David Foster: Brilliant quote from the Webbs.

AIG: Thank you for these charts. For years, we’ve been hearing about the skewing of the income curve UP, but I at least haven’t seen it laid out so cleanly.

Z in MT: I’m not so sure about 2) and its impact. Yes, the number of manufacturing jobs has declined, but the number of IT, healthcare, and programming jobs has expanded. And while the distribution of incomes may be skewing up, I wonder about statistics regarding the to 10 or 5 or one percent.

As economist Thomas Sowell told Ricochet’s Peter Robinson on Peter’s WSJ/Hoover program, Uncommon Knowledge, not long ago (in a remark similar to the Marginal Revolution posting that David Foster links to), “56 percent of American households will be in the top ten percent [of incomes] at some point in their lives, usually when they’re older [and] of all the people who are in the top one percent in the course of a decade, the majority, the great majority are there only one year; only 13 percent are there two years” (http://bit.ly/Sowell56percent, quote at 13 minutes 14 seconds).

Similarly, the president of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, James Bullard, noted in a talk to the Council on Foreign Relations recently that “life cycle [that is, where you are in your working life, early, middle, or late]… accounts for something in the order of 75 percent of the story of measured income and wealth inequality in the U.S.” (http://bit.ly/Bullard75percent).

TKC101: While I am concerned about the rent-seeker state, I am sure you are wrong that there has been any group in the country with an interest in higher oil prices and the market strength to enforce them. Saudi Arabia? Yes, though their market power seems to have vanished. My worry is that, if mobility is indeed stalling in the U.S., finding the fault in sectors (manufacturing or energy) will distract us from addressing government policies that stifle the dynamism that has been the country’s enduring vehicle for upward mobility — both for those who create businesses and those who join their teams.

Well, you’ve all toughed upon this theme that “middle class” relies upon a…preference…for economic stability.

But therein lies the problem. Economic stability is not what “the market” offers. It’s what the government offers, mainly through anti-competitive policies (be it anti-competitive in the domestic market, in the international market or in the labor markets).

Capitalism, is inherently anti-stability. And that’s how it produces economic gains.

Since both parties have decided to go down the “middle class economics” avenue of attracting votes, we have to remember the experiences of the UK over the last 70 years. At least within the Anglosphere and within countries with similar economies to the US…no other county went down the path of “middle class economics” more so than the UK.

With devastating results. At least until Thatcher came around and reversed it (somewhat).

So the “middle class” is just as “anti-capitalist” as any other group of people. After all, no one likes competition, and no one likes uncertainty and volatility.

But the government should not be in the business of preventing competition, reducing uncertainty or eliminating volatility. All (or most) such attempts are just soft-socialism. Or in the case of the UK up until Thatcher, pretty hardcore socialism.

Well it seems to me the majority of the movement has indeed happened towards path 1.

In 1967 we can see about 17% of households in the bottom category, but in 2007 (in 2011 there was a slight increase, for obvious reasons), we see only about 12% in that category.

If we compare the “lower middle class” and “upper middle class” groups of 35-50 and 100-150, we see that in 1967 there were about 20% of households in the “lower middle class” group, and only 9% in the “upper middle class”.

In 2007, those numbers are virtually equal at about 18%. That’s a slight decrease in the “lower middle class”, but a doubling of the “upper middle class”.

Trends seem to look a lot more attractive to me today, then they did in the “good old days” of 1967. Yet politics, seems to be stuck in the “good old days”, focusing on jobs that are dead or dying, on industries that are dead or dying, and on anti-competitive policies to protect “jobs and industries” that will only be counter-productive.