Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Why Philosophers Hate Economists

Why Philosophers Hate Economists

I can’t be the first person on Ricochet to have noticed that philosophers and economists don’t always get along. The tension between the two bears some resemblance to the tension between conservatives and liberals. As the old trope goes, conservatives believe that liberalism is wrong, while liberals believe that conservatism is evil. Similarly, when economists and philosophers disagree, the economists believe it’s because the philosophers aren’t making sense, while the philosophers believe it’s because the economists are morally bankrupt.

Do you have a theory about this? I do. Here goes:

Perhaps the main reason philosophers hate economists is because philosophers and economists both use the same word to mean very different things. To be fair, philosophers used the word first (philosophers existed way before economists). But you’d think philosophers would have no problem understanding that some words are simply semantically overloaded, and this word is one of them.

If you haven’t guessed what the word is by now, it is “rational” (along with its sister word “rationality”). My understanding of philosophy is somewhat on the shaky side, but it seems to me that philosophers generally consider a rational actor to be one who is both self-aware and capable of discursive reasoning.

To an economist, being a rational actor requires neither self-awareness nor discursive reasoning. Rather, being rational in the economic sense simply means responding fairly predictably to incentives. By this logic, even trees could count as rational actors, as Milton Friedman hypothesized:

Let us turn now to another example, this time a constructed one designed to be an analogue of many hypotheses in the social sciences. Consider the density of leaves around a tree. I suggest the hypothesis that the leaves are positioned as if each leaf deliberately sought to maximize the amount of sunlight it receives, given the position of its neighbors, as if it knew the physical laws determining the amount of sunlight that would be received in various positions and could move rapidly or instantaneously from any one position to any other desired and unoccupied position.

Now some of the more obvious implications of this hypothesis are clearly consistent with experience: for example, leaves are in general denser on the south than on the north side of trees but, as the hypothesis implies, less so or not at all on the northern slope of a hill or when the south side of the trees is shaded in some other way. Is the hypothesis rendered unacceptable or invalid because, so far as we know, leaves do not “deliberate” or consciously “seek,” have not been to school and learned the relevant laws of science or the mathematics required to calculate the “optimum” position, and cannot move from position to position?

Clearly, none of these contradictions of the hypothesis is vitally relevant; the phenomena involved are not within the “class of phenomena the hypothesis is designed to explain”; the hypothesis does not assert that leaves do these things but only that their density is the same as if they did.

Despite the apparent falsity of the “assumptions” of the hypothesis, it has great plausibility because of the conformity of its implications with observation. We are inclined to “explain” its validity on the ground that sunlight contributes to the growth of leaves and that hence leaves will grow denser or more putative leaves survive where there is more sun, so the result achieved by purely passive adaptation to external circumstances is the same as the result that would be achieved by deliberate accommodation to them.

Most likely, a philosopher’s gut reaction is that calling a tree a rational actor debases the very concept of rationality.

Hopefully, his second reaction is that different disciplines may use the same word in different ways without debasing each others’ concepts, but I doubt many philosophers get that far. Not because philosophers are unusually obtuse, but because our own conception of rationality is so bound up in our self-identity that we instinctively want to defend “our” definition of the word in order to defend who we are:

Being human means being a motivated reasoner, even when you’re a philosopher.

Philosophers might find some consolation in the fact that good economists do indeed know how weak the economic notion of rationality is. As Ronald Coase (an economist so insightful that he won a Nobel prize for work that included no calculations beyond simple arithmetic) put it,

The rational utility maximizer of economic theory bears no resemblance to the man on the Clapham bus [the British equivalent of the man on the street] or, indeed, to any man (or woman) on any bus. There is no reason to suppose that most human beings are engaged in maximizing anything unless it be unhappiness, and even this with incomplete success…

[W]hatever makes men choose as they do, we must be content with the knowledge that for groups of human beings, in almost all circumstances, a higher (relative) price for anything will lead to a reduction in the amount demanded. This does not only refer to a money price but to price in its widest sense.

Whether men are rational or not in deciding to walk across a dangerous thoroughfare to reach a certain restaurant, we can be sure that fewer will do so the more dangerous it becomes. And we need not doubt that the availability of a less dangerous alternative, say, a pedestrian bridge, will normally reduce the number of those crossing the thoroughfare, nor that, as what is gained by crossing becomes more attractive, the number of people crossing will increase.

It’s unfortunate, in retrospect, that “rationality” should be the economic shorthand for “responding fairly predictably to prices in their widest sense”. If economists had simply used a different word, I think they’d get a lot less hate from philosophers. Moreover, us ordinary folk would have one less overloaded term to deal with. It’s difficult to carry on a conversation when people use the same cluster of letters to refer to such wildly different concepts, especially when both concepts are intimately tied to human identity.

Published in General

Speaking of art and Eros, the middle installment of my series of Lenten music posts has finally made it over to Rico 2.0! It features the music of Orlande de Lassus, a guy who used the tunes from naughty drinking songs (such as “Oh, you fifteen-year-old girls!”) to write ravishingly beautiful masses. The curious can read more here.

Let me try a different approach: I have never heard someone object to Friedman’s tree example on the grounds that it uses the wrong meaning of “rational.” They object because it’s flat wrong. Trees do not position their leaves, nor do they maximize exposure to sunlight. Tree leaf positions are governed by a growth hormone. It can be modeled by mathematics, but the math isn’t causing it. It’s excessive anthropomorphizing -and while I’ll accept anthropomorphizing as a shorthand to explain something, Friedman is actually using it to theorize.

Friedman is the scientist: “look, my predictions work, don’t they?”

Biologists can point out that his predictions being right bear no relation to him actually understanding trees. While he might tell us a little about how leaves form, it obscures the far more interesting mechanical process.

And Friedman asks -“why complicate things?”

To which the philosopher can respond: “One assumes a mechanical process, the other a rational process, and we have no evidence one way or the other. Perhaps the growth hormone appears where it does because it mimics an ideal plant form?”

And Friedman and the biologist say “why complicate things?”

Is it really necessary, though, to preface Maxwell’s equations or the uncertainty principle with the statement that “if the universe is purely material and mechanistic, then…” Do you really need to believe that Everything That Exists is purely material in order to believe these theories?

I doubt it. (For one thing, I know physicists who are devout Christians.) Mathematics is even odder, as it has no real materialistic component.

Is it normal for scientists and economists to not be acutely aware that they’re working with models of reality, not the reality itself? I had that lesson hammered into me pretty early. Was I just lucky?

I hesitate to jump in here because I have an strong interest in economics and everything we do on Ricochet is applying philosophy to some extent, but I’ve never seen much utility in the pure philosophical aims, as in assuming nothing unless it can withstand radical skepticism or constructing a beautiful moral framework just to have your assumptions challenged. But don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying philosophy is worthless in the least. Like Midge said, even if people are assuming things that are not irreducibly true, their conclusions may still give some clues about the true nature of life.

That being said, Bryan Caplan has a list of things he learned in his first 40 years of life, and I like his take on philosophy. A small excerpt:

– The greatest philosophical mistake is to demand proof for the obvious. See Hume.

– The second greatest philosophical mistake is to try to prove the obvious. See Descartes.

Apologies Midge for not reading this when you sent it to me, the inbox alerts haven’t worked yet and I didn’t see it until after it was promoted to the main feed. Well done!

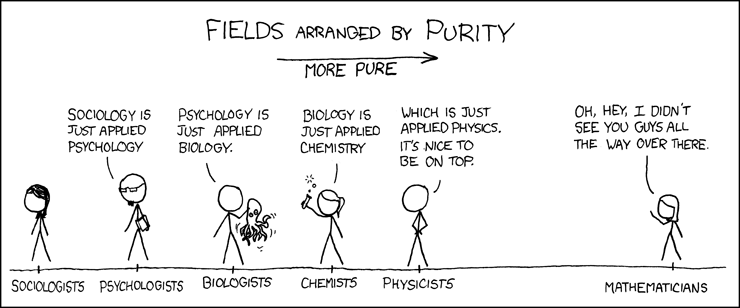

I like Descartes because he made the discoveries of the Church Fathers palatable again. Cogito Ergo Sum is really just Augustine’s I have sinned therefore I am, and the difficulty of knowing much is just a weaker and less accurate form of Psuedodionysus. The greater thinkers that Descartes points to remind us of the absurdity of the sceptic’s straining at gnats in believing the gospel. By emphasizing the limits of reason on a theoretical basis, they provide an important foundation for Burke’s work, which assumes the limits of reason. Think of Descartes as chemists in this XKCD cartoon (the mouseover text if you follow the link is Ricochet themed if not Ricochet appropriate).

The error I mentioned does certainly happen. I’ve been in conversations with economists who pretty clearly make that mistake and even go so far as to suggest that a theory I have laid forth couldn’t possibly have any merit because they *couldn’t even model it*.

The connection others have made to scientism is a good one. One needn’t be a materialist to study the material, but ordinary human pride always makes us want to elevate the importance of whatever we personally study and understand, so it easily happens. EThompson is gesturing in that same direction with her references to economics as the study of “the real” and philosophy as “a dream”.

With your references to Scruton, I guess it just sounds to me more like he failed to argue the particular points that were of most interest to you personally. That can happen of course, but it isn’t the same problem. As Sabrdance well explained, the trouble with many economists is that they haven’t adequately examined the ontological foundations of their worldview. Philosophers are less likely to make that mistake.

Hormones are the proximate cause, but hormones are chemical messengers, and messengers are used to carry signals, and it’s not really that odd for human beings to want to decipher what those signals are and might signify.

To say “Because hormones,” is an accurate explanation. But it is also an incomplete one. What are those hormones doing there?

The video was well done. Though when she says, “Not just because it mathematically optimizes sunlight exposure if the sun is right overhead, which it pretty much never is ,” she’s saying nothing that, by itself, invalidates all theories of sunlight optimization, since the sun is, as she says, pretty much never overhead.

She also says, “The best way to fit new things in with the most space has some pop up at that angle… because that’s where the most hormone has built up.” But why does the hormone build up at the places that are “best” for fitting new leaves in with lots of space?

The word “best” is typically a clue that some optimization is going on. Why would leaves “want” to grow as far from each other as possible? Might it be in order to get more sun?

MFR, the little I’ve read of Scruton backs up your opinion. I don’t see the greatness at all.

I assume, then, that you’re showing Cogito Ergo Sum is obviously silly? True, if I sin, then I am, and if I am not, then I do not sin. You could just as easily say, if I breathe, then I am, and if I am not, then I do not breathe. But God doesn’t call things into existence because they sin. Our sinning doesn’t prove irreducibly that we are. (It is, though, evidence of our freedom.)

I hadn’t heard that one before, and I was teased a lot for “going over to the dark side” as the physics majors put it. But is math that , or is it choosing another lover, albeit one less tangible than the equipment in a physics lab?

And if Ricochet is all about that , at least that is undertaken mutually and we learn from each other in the process.

How much of what passes for economics as generally understood stands up under the scientific method? Comparative advantage? What else?

As highlighted in comments by anonymous re: the knowledge problem and another re: Coase and the firm, some of the most profound economic insights have been epistemological, not quantitative.

The stuff we see on TV every month are mere “counting stats,” as the sabermetricians like to say.

That is clearly the hierarchy and at Caltech they sort you explicitly in this manner. My brother has some tales (he was a mere ChemE).

Are you confusing necessity and sufficiency? God did not create us to sin, and created many things that do not think or breathe, but all of the things that actually breathe, sin, or think exist.

That said, I shamefully mangled my Augustine, removing much of the profundity and humor. His argument was “If I am deceived, I am“. This might seem obvious, but there have been plenty of intelligent philosophers who denied it, and a definitive rebuttal seems valuable to me.

How is it not the same problem?

When you, for example, object to people using economic reasoning, you typically say they failed to address particular philosophical points, which you notice so acutely because they are of interest to you personally, since you’re a philosopher.

In sum, what you notice is people failing to argue the particular points that are of interest to you personally.

I think that Ricochet can be productive. I hope, for instance, that my fundraising efforts here might help others to conceive something useful. As I suggest regarding Descartes, though, the purer disciplines can be useful both in preparing the ground for results from the applied disciplines, and in diminishing the appeal of those mistakes that can be rebutted with theory.

I guess I failed to communicate what seemed to me the vacuously true nature of “if I sin, I am”. It is vacuously true for the reason you pointed out: all things that breathe, sin, or think exist (even though many things that do not breathe, sin, or think also exist).

So saying “If I sin, I am” is true, but in a vacuous way that hardly justifies our existence.

You know how some people wish they could “like” comments more than once? Apparently we can like them as many times as we like. I just “liked” Midge’s comment above 8 times.

I suspected something weird like that must’ve happened. A sudden spike in all Ricochetians’ interest in my particular thread, and moreover in that particular comment, seemed too much to hope for.

You have eloquently stated both ends of the dispute as I have observed them. Non-philosophers as I have known them would typically object that “best” is also excessive anthropomorphizing -it is not best, it just is. Philosophers ask “why the leaves want?” Scientists dismiss the question as anthropomorphizing the inanimate.

I think that Marx made some of Aristotle’s mistakes, but that he remains on of the finest thinkers on the structure of the modern world. I think that his understanding of the way that our positions in society affect our understanding of society, together with the corollary that increasing wealth has an intrinsic and unavoidable democratizing influence to be amongst the most important discoveries of the 19th century. I like Mill, too, but thought he discovered less of use and more that was wrong.

With Kojève, I think that the West today is a close approximation to Marx’s utopia, and believe this to be a very good thing. My particular political obsessions mostly (rule of law, the Pax Americana, free trade, the information problem, and incremental prosperity, but not Burkean thought) include a substantial nod to Marx. PM me your email address and I’ll send you a considerably more elaborate version (this goes for anyone; I intend to post it to Ricochet someday, but manana doesn’t always come).

Why do you think they hammer the lesson early? I hammer the lesson early. “The map is not the territory, the model is not the system, and your theory is not reality.” “Any model which includes every aspect of the system is the system, not a model.”

And yet very smart people continue to treat CBO projections of the stimulus as if they reflected reality and not the model assumptions. We talk about Austrians and Keynesians because generally they look at the same data, apply their theories, and get diametrically opposed answers -yet are both absolutely certain they are right -based on their theories. The argument is circular. Keynes says this, therefore this must be happening, which proves Keynes. And, hey, it predicts, and it helps us understand a little. Who cares if it’s true? It’s useful.

The same thing happens in philosophy -where ardent Utilitarians will adopt obscene positions to verify Utilitarianism because Utilitarianism is correct. Their positions prove it.

While I don’t disagree necessarily, it seems this pithy statement is going to collapse under the question: “What is obvious?” It seemed obvious to Descartes that animals didn’t feel pain -it was just reflex. It seemed obvious to Scruton that dogs don’t plan ahead.

I don’t see myself as wearing the science hat in one remark and the philosopher hat in the other. Rather, in both cases, I was doing my (admittedly humble) best to do scientific reasoning well. My two remarks came from the same worldview, not different ones residing within me.

Incidentally, I’ve observed that, in practice, scientists casually anthropomorphize the inanimate all the time. Atoms “want” to fill their electron shells by forming chemical compounds with other atoms. Etc. Ain’t nothing wrong with it as long as you don’t take it too literally and it gets the science done.

OK, you shameful mangler. I read Augustine’s argument, and yes, it does strike me as clever, and worth pondering (so, among other things, not obviously vacuous). It will take me a while to decide whether he’s merely playing a beautifully-constructed word game or getting at some deeper truth, but it is certainly something to think about. Thanks!

I think that this is a better riposte to MFR’s statement than my link to Augustine. That rescued Augustine from her contempt, but this elevates the whole field of gut instinct verification.

I have a theory about this (which is thin at one end, much MUCH thicker in the middle, and then thin again at the far end):

When a model is part of our focal awareness, it’s easier to remember that it’s just a model. When a model is part of our peripheral awareness, though, the fact that it is a model tends to fade into the background, just as everything in our peripheral awareness does.

We don’t have the time and energy to treat every model we use in life as if it were a model. Often, just to function, we treat models as if they were reality.

Ontology is more fundamental in the hierarchy of knowledge. That’s not because it’s of greater interest to me personally; it’s because things have to exist before we can characterize them. Philosophers think about what it means to exist, why things do, how the universe came to be and what that says about the kind of universe we’re in. Economists frequently make assumptions about *those* basic issues without defending or examining them. It leaves them “trapped in a model” without realizing it.

Meanwhile, you may not be persuaded of Scruton’s point about dogs and planning, but that’s not foundational to the entire nature of the discourse in the same way. It’s just a quibble you happen to have with him.

Philosophers frequently come in for criticism because of the level of abstraction of their discipline. (“It’s just a dream, economics is real.”) That’s understandable, and it’s absolutely true that philosophers, lacking the kinds of specific empirical constraints that scientists or economists have, wander into absurdities far more removed from reality than anything an economist would ever say.

Still, we at least have this: as the students of “first things”, we’re less likely to be confused about what it is we’re actually doing in our discipline. Everyone has to have some metaphysical presumptions in order to pursue further knowledge, but a lot of people make a hash of those and then brag about being more “real” or “data-oriented”… that’s when we get scornful.

We are all trapped in our models. Even (and especially, it seems to me) ontologists.

We all must make simplifying assumptions which we are content to leave relatively unexamined. Else where do we start?

What exists “out there”, independent of our models, will continue to exist and do its thing, even when we get our model wrong. Bad models may cause us to act in ways that injure reality, but bad models by themselves cannot negate reality.

Being human means being trapped in our models. I seriously doubt there’s an escape from this. Maybe in heaven, when we at last see God face to face. But not before.

I understand what you’re saying, and of course I’m not suggesting that ontologists are infallible or necessarily even wise. But there’s still a point to be made here about the hierarchy of knowledge. The study of existence is foundational to the study of anything else. You can’t go about characterizing the things that exist without having some views on the nature of existence. But because empirical science and economics are more, shall we say, prestigious or fashionable disciplines in our time, people often do kind of a messy job with the ontology, or just adopt one slap-dash without acknowledging the “debt” to philosophy. And they don’t especially like to hear about it from philosophers, because in our time the order of “disciplinary status” doesn’t line up with the natural hierarchy of knowledge. So they just do their bad philosophy and don’t worry about it.

Philosophers can still be myopic and narrow-minded and obtuse and whatever else, but because their work isn’t dependent on the work of these other disciplines in the same way, they aren’t prone to precisely this same mistake.

Specifically in economics, lazily sliding from descriptive to normative claims without any intermediary moral bridging is a *very* common thing. I’m sure the terminology-confusion you describe does happen, but that’s not the whole story. Economists can get very used to seeing their work of “maximizing rational preferences” (understanding rational in the more limited economic sense you have described) as a moral imperative. If “rational” were understood in a full Aristotelian sense, it would be a moral imperative, but as you’ve noted the two senses of “rationality” are really quite different.