Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

How to Think About Inflation and Deflation — James Pethokoukis

How to Think About Inflation and Deflation — James Pethokoukis

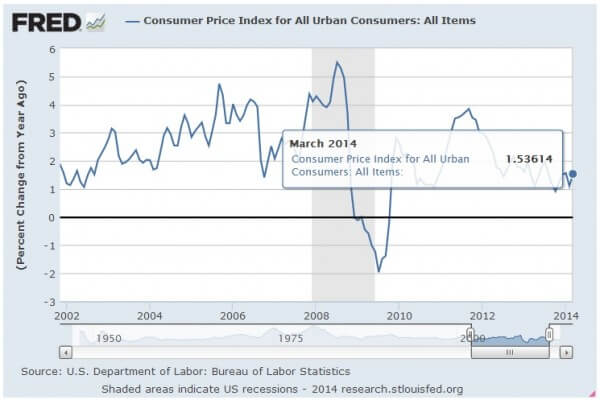

The March consumer inflation numbers showed prices rising faster than expected and up from last month. In the 12 months through March, consumer prices increased 1.5% versus 1.1% in February. The core CPI, which strips out the volatile energy and food bits, rose 1.7% versus 1.6% in February.

The March consumer inflation numbers showed prices rising faster than expected and up from last month. In the 12 months through March, consumer prices increased 1.5% versus 1.1% in February. The core CPI, which strips out the volatile energy and food bits, rose 1.7% versus 1.6% in February.

Analysis from IHS Global Insight:

Overall, the consumer inflation story is relatively bland. However, the direction of food prices is somewhat worrisome. Average consumers will have no cause to consider inflation rampant, but living standards will suffer as a larger percentage of household budgets are spent on grocery store bills, leaving less for discretionary spending.

Overall, inflation really is benign, especially given the Fed’s avowed 2% target. In fact, some economists have been worried that inflation has been too low, maybe risking outright deflation. As AEI economist John Makin wrote in a recent report, “Inflation is falling in the United States, Europe, and China, suggesting a real threat of impending deflation that could cripple the global economy.” To get some more insight on inflation, I asked a few questions of Makin, and economist/blogger Scott Sumner of Bentley University:

PETHOKOUKIS: There seems to be concern out that that inflation is running too low. But isn’t low inflation a good thing? Isn’t that the great Volcker victory of the 1980s? Along those lines, are some kinds of inflation and deflation good or bad?

MAKIN: Low and steady inflation is a very good thing. Volcker withstood immense heat for the pain tied to bringing inflation down from 10% to about 3%. But the benefits were substantial– avoiding destabilizing higher inflation and setting the stage for a huge equity bull market after 1982′ when he relaxed tightening. The drop in inflation cut tax receipts so much that the deficit rose faster than expected – a constructive form of fiscal stimulus.

Relative price changes, brought about by rapid price increases or decreases in some goods/ services are good and self-correcting. But when most prices are rising or falling consistently, movements can become self- reinforcing and damaging to the economy. Higher inflation is usually more volatile. That boosts uncertainty in a way that has been shown empirically to harm growth. Disinflation is fine, until and if it turns into deflation which almost always is associated with lower growth, weaker investment and higher unemployment — as in the Great Depression and In Japan after 1997.

SUMNER: Never reason from a price change. Whether inflation is good or bad depends on whether it is supply or demand-side inflation, and whether aggregate demand is currently excessive.

In short: (a) Supply side inflation is bad, but it isn’t really the inflation that hurts, it’s the fall in real GDP from the adverse supply shock. Thus holding nominal GDP constant, higher prices mean less real output, which is bad; (b) Demand side inflation can boost both prices and output, which can be good. But only if the economy is currently depressed from an adverse demand shock. In my view that’s been true of the US economy since late 2008, although it becomes a bit less true as unemployment falls back closer to its natural rate (which is hard to estimate.)

In my view it makes more sense to talk about boosting nominal spending than boosting inflation, because that language better conveys what the central bank is actually trying to do.

In terms of the trend rate of inflation, Volcker was surely wise to bring it down from double digits. But all he did is bring it down to 4% in late 1982, where it remained throughout the rest of the 1980s. Today it’s about 1.5%, so a bit higher inflation would be needed if the Fed is serious about its 2% long run target. There are costs and benefits from a lower or higher trend rate, and no one (including me) knows what trend rate of inflation is optimal. I suspect it’s close to 2%, but the exact rate depends on other aspects of policy. Under current (inept) Fed policy it’s probably close to 3%, as that makes the zero bound on interest rates less likely.

PETHOKOUKIS: It looks like the ECB might start a quantitative-easing, or bond buying program. Would that help the EZ economy?

MAKIN: The usual criticism of incipient QE or other anti-deflation measures is that they won’t work. Japan suffered under this delusion for 15 years until late 2012. Successful reflation requires a higher inflation target from the central bank that it is committed to meeting with substantial money printing until prices start to rise– the exchange rate starts to fall. A central bank has to credibly promise higher inflation to beat deflation. Many cannot bring themselves to do it, as is I fear, the case with the ECB.

SUMNER: QE would help in the eurozone, but I’d prefer they set a nominal GDP target, or if they continue to inflation target they should do level targeting of prices, which means promising to catch-up for any shortfalls from their inflation target (assumed to be about 1.9%).

Published in General

Looking at that chart, does anybody really believe that the money supply shrank in 2009?

I feel like I’m in bizzaro land. How do economists keep a straight face when claiming they are fighting deflation when there is no deflation?

no.

I remain unconvinced of the avoid-deflation-at-all-costs approach to economics. Are deflationary spiral and depression really the only possibilities? If there is such a thing as benign or even beneficial inflation, why wouldn’t there be deflationary counterparts?

How is this damage assessment made, and from whose perspective? Consumers’, priducers’, government? Sometimes the numbers/performance just are what they are, right? Doesn’t meddling with true performance by imposing artificial targets lead to bubbles and spirals?

I concede that deflation is more damaging then inflation, but inflation is presently sitting at about the ideal level. Why are economists still pounding the deflationary drums?

Perhaps there are periods where there’s reason for growth to be low, investment to be weak, and unemployment to be higher. It’s an unreasonable expectation that GDP and value will do nothing but go up in aggregate, isn’t it?

I’d say that it depends on circumstances and perspective. More damaging to whom (or should that be who)?

Either way, though, don’t we run a risk of bigger damage by meddling with the normal ups and downs? Don’t we run the risk of increased volatility?

Simply google “deflation” and “myth” for all sorts of discussion:

http://lmgtfy.com/?q=deflation+myth

I’m not sure how much I buy that one economist could have this much foresight and impact. If so, then why do we ever suffer a bad economy? The best they can do is try to mask natural pain and defer bad effects, but that pain always asserts itself in the end.

Aside from that, doesn’t this also illustrate the point that no remedies can be prescribed without side effects? So Volcker valiantly brought down bad inflation and set the stage for the bull markets of the 80’s and 90’s. Wasn’t it at the cost of kicking off three decades of at least partly debt driven growth, though?

Aside from that fact that Sumner just got finished saying, in the section previous to that quoted, that supply side inflation is bad (isn’t that exactly the type of inflation that would result from QE?), why do they theink that it should be a central bank’s task to “reflate” an economy? What makes them think that a central bank is powerful enough to do anything more than to temporarily mask the real state of things?

So we’ve had basically uninterrupted inflation since the Depression. Economists have chosen this as the best strategy. Hasn’t that inflation contributed, at least in part, to the exodus of manufacturing (and jobs) to other countries over those decades? Didn’t that contribute at all to companies’ decisions to delay capital improvement (because it was so expensive) until it was too late to catch new competition anyway?

My understanding is that loans (or corporate bonds or what have you) would have inflation expectations built into them and sudden increases in the rate of inflation would benefit the debtor not the creditor. Inflation is the increase in price across the board so I don’t know if it’s related to outsourcing. I think the reason companies go overseas is that we would demand better pay and working conditions than people would at, say, the Foxconn plants in China. Also, I don’t think they need to worry about unions! :) I’d be interested to hear an economist answer these questions though.

The chart is for consumer price index. I think the price of oil crashed around 2009 after the recession so maybe that lowered prices across the board. Maybe? Possibly?

But that’s a static evaluation of a specific transaction after the transaction is complete – a silver lining for the current transaction and an inducement for the next one. It says nothing about whether I (or “we” as a whole) would be better off overall with more or less inflation. Otherwise, inflation encourages borrowing/spending: doesn’t that bolster the point that the policy of inflation has at least contributed to the transformation from a producing/saving country to a consuming/spending country?

True, but starting production from scratch in a foreign country is expensive in itself, let alone the cost of acclimating to the new culture, government, workers, and training. Without inflation could domestic wages and resource costs have stayed low enough to make a costly move unattractive even if the estimates showed marginal improvements to the bottom line?

Also, moving production to a foreign country makes sense if an owner can still maintain or improve their standard of living in the home country. If all owners do that, though, then can we really expect the standard of living in the home country to remain unaffected?

Honestly who can really say how substantial an impact monetary policy would have on that? It could simply be a cultural shift where the generation that suffered through the depression and saved is replaced by a generation that has only known prosperity and has a lucrative safety net. When I was going to school I overheard a woman on the bus advising another that “it’s not a sin to die in debt”. I doubt they’re doing real interest rate calculations there.

Can our economy even survive a majority of people not buying every iteration of phone/video game/car at release prices? Maybe we’re caught in a crazy catch-22.

Sumner said no one knows the optimal rate of inflation but it’s ok so long as it’s low and stable. Whatever the case, deflation is more than likely not the answer.

Yes, we likely can survive it. Prices will come down like they have with TV’s and such. How many of these products are produced here anyway?

Why?

If there were long term deflation and if wages were stagnant that would mean workers get an automatic wage increase every year because their x dollars/hr buys more year on year. Eventually their wages will have to be cut or people would have to be laid off. This is across the entire economy. Not to mention you’d pay more on loans year after year which might disincentivize investment.

Prices can move for reasons not related to monetary policy. Oil prices go up because you need fracking and enhanced recovery now instead of an errant shotgun blast. Plus if I expect a certain lifestyle I could opt to just not take an otherwise good position if I think they pay too little or join a union or something. Again, I’d be interested to hear a trained economist weigh in but that’s how I see it.

Well sure, but I’m not advocating long term deflation or pulling levers and twisting knobs to achieve deflation. I’m not advocating either inflation or deflation as better than the other, necessarily. I’m mostly just suggesting that deflation is a real, natural, and sometimes desirable part of an undistorted (less-distorted) economy; also that inflation all the time as a policy is unrealistic, damaging, and undesirable.

Interesting discussion. On the topic of deflation, I live in Hong Kong, and we had over four years of deflation in the early 2000s. It was Not Good. Cantankerous Homebody is right on the money with the cautions.

If you think wages remain steady so that workers realize a gain every year — well, that is not what happened here. Most people in HK’s private sector took serious pay cuts, often 10%-30%, and people in government jobs took incremental cuts strung out over years. I work in a university whose pay scale is based on the government scale, so it meant my pay didn’t come back to 2000 levels until 2010.

The other big effect deflation has is severe economic stagnation. Layoffs, suppression of entrepreneurial impulses, lack of borrowing — yes to all. Property prices also plummeted, so even if you felt good going to the grocery store and paying less, you’d take the food back home to a flat with an underwater mortgage.

The thing that spooked people most about it is that there’s no clear way out of deflation. It tends to linger for a long time, even in an economically vibrant place like HK.

There was a spike in prices around 2008/2009. I remember it; at the time I was a college student, and had to cut back on what little disposable purchases I was making. That was more a matter of the oil shock than anything else, I think.

Economically speaking there isn’t a reason. It has to do with political economy: in a world of universal suffrage, the only way to get workers to take pay cuts is with inflation. To my knowledge, few people experienced nominal wage cuts after the 2008 crisis (when wages simply had to go down). Instead, inflation did the job.

So, by extension, in a deflationary period, labour costs for an employer would get out of control pretty damned quickly, since they’d effectively be getting raises with every passing day.

Sounds like your experience with deflation is decidedly outside of the reasonable band under discussion here. After all, 10%-30% inflation is just as destructive.

I’ve seen this discussed on several threads here and in other media, and it seems that the flaw in many of the discussions are inapt comparisons: comparing 2% inflation to hyper-deflation. Obviously “hyper” one way or the other spells catastrophe. But what about -2% vs +2%? If the deflation is occurring too rapidly or too much, don’t we have handy tools to fix that, i.e. printing money and raising interest rates?

The problem is you can raise interest rates as high as you need to to cripple inflation, but if you go too far in the other direction there’s nothing you can really do about it. That being said, I think interest rates do not need to be zero now and all quantitative easing was a mistake that only didn’t spell catastrophe because no one took the bait. QE also is contributing to economic malaise because banks are being rewarded for not lending money.

QE is also a form of socialism in it’s more literal sense.

Can’t we increase money supply in that case? Also, if we end the default inflationary target then wouldn’t that mean a gradual increase of interest rates? If we start to deflate too much then couldn’t we just lower the rates again?