Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Monday Morning Science: The Order of Things

Monday Morning Science: The Order of Things

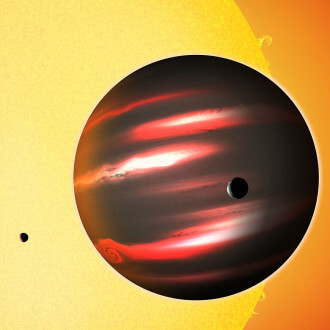

By David A. Aguilar (CfA), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16206794

If it seems that the last decade has brought us one discovery of exoplanets — i.e., planets orbiting stars other than our own — after another, you’re not wrong. The field is only a few decades old and, in that time, we’ve gone from knowing very little about a handful of other systems, to a knowing good deal about thousands. This last month, however, has been truly spectacular and changed how both the general public and astronomers understand what else is out there.

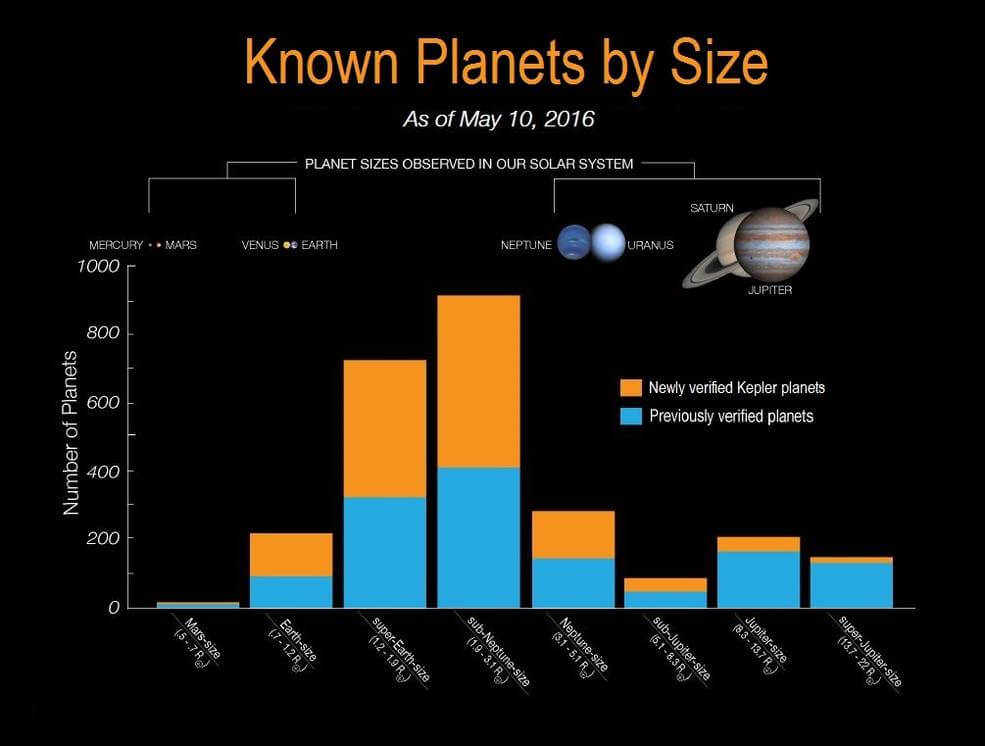

The first change comes from courtesy of the Kepler Space Telescope and its team, who announced — in one fell swoop — the discovery of nearly 1,300 likely planets, an addition that increases the total number of planets ever discovered by nearly 50 percent (if this sounds somewhat familiar, that’s because the Kepler team announced the discovery of some 700 planets back in 2014). Kepler is a space-based telescope, launched in 2009, that orbits the Sun just a little outside the orbit of the Earth for the specific purpose of planet-hunting.

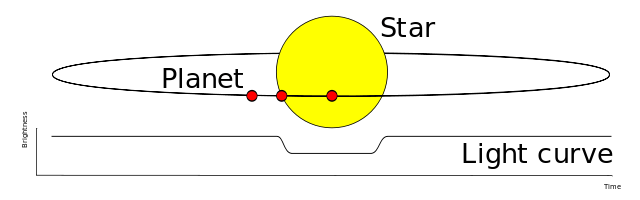

Though other methods of locating planets abound, Kepler relies on the Transit Method, in which the dip in light as the planet passes between its star and the Earth; essentially, think of it as a mini-eclipse of that star. Though this only works for planets with orbits that are the same as the Earth relative to its star, it requires far less precision than other methods and also yields the planet’s size. If you combine transit method data with that from other methods — such as say — the Doppler method, you can calculate the planet’s minimum density, which tells you something of its composition.

By User:Nikola Smolenski – Inspired by image at http://www.iac.es/proyect/tep/transitmet.html, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=487277

The new data are substantial enough to change what we should think a “normal” solar system looks like. Until just a few decades ago, the only planets we knew of were those of our own solar system and our guesses about what other systems were like were largely influenced by our own local arrangement. Moreover, there seemed to be a strong pattern among them: rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars) were closest to the sun, followed by gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn) further out, followed by ice giants (Uranus and Neptune), followed by Pluto and other Kuiper Belt Objects. Given that this was pretty much all we had to go on, it was widely assumed that something like what happened here was the norm and all kinds of theories were offered to explain why our system is the natural arrangement for planets around a star.

Those theories ended up in the dustbin when we started finding extrasolar planetary systems that were nothing like our own. One of the more sensational finds was the new class of “hot Jupiters,” massive planets that orbit other stars far closer in than Mercury does ours, and many with highly eccentric orbits; that is, they orbit their stars in long ellipses with one end close to the star and other much further out (in contrast, the planets of our own system have orbits that are nearly circular). It’s not surprising that hot Jupiters dominated the early discoveries: our methods of discovering exoplanets favor both large ones and those close to their star; it’s just that we had no reason to suspect they existed at all.

The new finds announced earlier this month are giving us a somewhat more balanced picture of what’s out there. The most surprising thing among this latest trove is the abundance of planets that are bigger than the Earth, but smaller than the Ice Giants, a class of world of which we’d had no prior knowledge until just a few years ago. As we’re working off information from Kepler, we only know their sizes, so their composition is largely guesswork; it’s assumed, however, that those roughly the size of the Earth are rocky, while those closer in size to the ice giants are more like them, but this is largely speculation.

One of the great oddities is that this further increases the current — and ironic — trend of knowing more about solar systems relatively far away than those close by. This is because Kepler — which has now found more than half the planets ever discovered — was designed to monitor thousands of stars simultaneously by pointing at the same location in perpetuity. As the stars in our immediate neighborhood are in all directions, very few of them fall into Kepler’s line of sight. For an analogy, if had only a telescope and were trying to learn more about when other families left home, you’d likely find it productive to look at the neighborhood across the bay than to try to monitor your closest neighbors (as there’s no way to monitor your immediate neighbor to your east and west simultaneously). Indeed, we’re still not sure whether the Alpha Centuari system — the closest to our own — has a planet (one was announced a few years back, but the claim was subsequently retracted; there’s another candidate but it’s not been confirmed).

Still, sometimes you get lucky, and it so happens that one of the closer stars within Kepler’s field of view — only 40 light years away; Kepler looks more than 1,000 light years out — has something pretty amazing going on. If the data pan out, then it appears that this barely-there star has three Earth-sized planets buzzing around it. Though the star is very dim, the planets are so close to it — all three are well within Mercury’s orbit of the sun that they’re likely within the stars’ habitable zone. Unfortunately, this also puts them close enough to be tidally locked to their stars, which one face of the planet is constantly bathed in sunlight while the other is in permanent night. If this sounds dicey, it is, though there’s a possibility that one or the other of them have a “Goldilocks zone” along its terminator (the line between day and night) that might be decent and could, in theory, harbor life. The upshot is, even the systems most like our own are still wildly alien to us.

Of course, our understanding of our own solar system is undergoing massive changes as we speak. In just the past year, the likelihood of a hitherto massive, unseen planet went from science fiction, to a very serious matter indeed. And just a few weeks ago, new evidence came in that suggested that an object found in the Kuiper Belt a few years back may be nearly as big as Pluto.

It’s not just the neighborhood or region that we’re having to re-imagine, but our very own home.

Published in General

We still need to get a couple more Keplers up, 120deg out from each other in their orbits (more would be better, including 3 or so in polar orbit), each equipped with really good clocks.

There would be a VLA detection system, and it would let us read G’Kar’s newspaper over his shoulder. As well as spot some truly Earth-sized planets and learn some stuff about other solar systems.

Eric Hines

Do any of these thousands of planets have a worse field of presidential nominees than us? I doubt it.

I would not read over G’Kar’s shoulder if I were you. He might take offense. You know what’s worse than an offended Narn? An offended Narn with a baseball bat in his hand.

I’m sure SMOD has his hands full and will get around to us eventually.