Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Falling in Love with America

Falling in Love with America

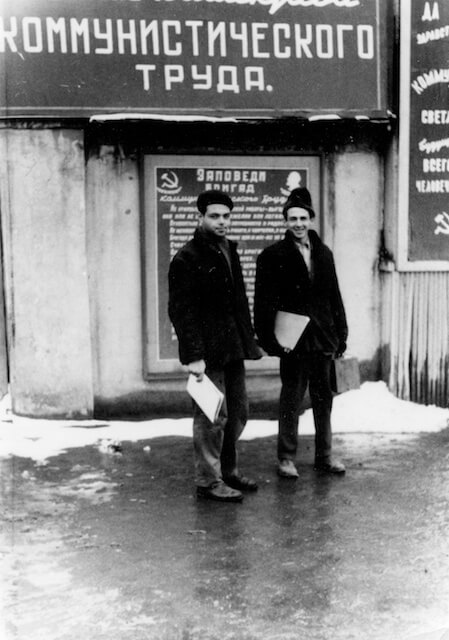

My father’s love affair with the United States began in the grim industrial city of Chelyabinsk in the central Ural Mountains.

My father’s love affair with the United States began in the grim industrial city of Chelyabinsk in the central Ural Mountains.

Dad had been lucky. In October 1941, as bombs fell all around them, he and most of his family fled their home in Kharkov just steps ahead of the advancing Germans, who occupied the city and over the next two months murdered the 15,000 Jews trapped in it. The family fled east, enduring the first desperate winter of the war in Orsk, on Russia’s Central Eurasian steppe, where the snowdrifts sometimes completely buried the small wooden house they shared with a local family. After the spring thaw, they trekked north to Chelyabinsk, where my grandfather had been assigned as chief engineer at a small ceramics factory.

This position entitled him occasionally to receive American care packages containing Spam, canned corned beef hash, powdered or evaporated milk, instant coffee, Wrigley’s chewing gum, Hershey’s chocolate bars and cigarettes. The purpose of the chewing gum, which contained little in the way of caloric content, was a fathomless American mystery. The cigarettes were, of course, more useful. No one in the immediate family smoked, but the Luckies, Camels and Chesterfields served as a universal store of value and an efficient means of exchange that could be bartered for black market luxuries like soap and flour. Sometimes the packages contained clothing or excellent American wool blankets that, with clever tailoring, often found a second life as coats or suits.

These packages also occasionally included handwritten greetings from the American families who assembled them under the auspices of the American Committee for Russian War Relief. Most of these messages were intercepted by the authorities, but some slipped through. One such package contained a note written on a color postcard of downtown Minneapolis. Dad, now 5 or 6, had stars in his eyes. He kept the postcard for years, and the image of the mythological-sounding city held him in a spell that was broken only some 40 years later, when he actually visited the Twin Cities (no childhood fantasy survives first contact with reality).

The family returned to Kharkov in the fall of 1944 to begin to rebuild their lives. Before the war the city had been the Soviet Union’s third industrial and cultural center after Moscow and Leningrad, and a major strategic prize. By the time the evacuees began to trickle back from the east, the city had changed hands four times, each time with heavier fighting and more destruction. They returned to a shattered, burned-out ghost town.

Groveling before the West

For most of dad’s early life America remained a siren song – a beguiling, shimmering, dangerous mirage. The living incarnation of that danger was Zalman, my grandfather’s youngest uncle, barely older than himself, known to dad as Uncle Ziama. Toward the end of, and shortly after the war, Ziama had spent some time in New York as a member of a Soviet trade delegation, wrapping up some technical aspect or other of Lend-Lease.

It would require an almost superhuman imaginative effort to begin to grasp the mind of a Soviet citizen – even an educated and privileged Muscovite like Ziama – who in 1945 finds himself transported into the very beating heart of the unrivaled, globe-bestriding atomic colossus at the apogee of its power – unscathed by war, bristling with skyscrapers, pulsing with energy, commerce, industry and optimism, bustling with throngs of well-fed, well-dressed people who have only the vaguest understanding of the words “rationing” and “shortages”, the New York of Charlie Parker and Richard Rodgers, and of Broadway, surging with automobiles and burning brilliantly again after three years of wartime “dim-out”. Ziama had landed on an incomprehensible alien planet.

Ziama’s first-hand experience of the United States had made him, by a wide margin, the big celebrity in the family, even eclipsing for a time its other star, a major-general who had been the Red Army’s intel chief for the Far Eastern Front during the war. But as the Cold War descended, “rootless cosmopolitanism” and “groveling before the West” became criminal acts and, unbeknownst to him, dark clouds gathered around Ziama.

During this time my grandfather’s star was rising, and he began to have frequent business with the Moscow ministries. By 1947 he was the engineering point man for the production of ceramic tile façades for Stalin’s new architectural showpieces – seven Totalitarian-Gothic skyscrapers, with wedding-cake profiles and soaring metal spires, scattered across the Moscow skyline. Today a clump of bland futuristic glass and steel towers rises above the city’s center, but Stalin’s seven triumphal monuments to the Soviet Union’s post-war power – Moscow State University, the Ukraina Hotel, the Foreign Ministry, a few others – still stand, as iconic to Moscow as the Empire State Building to New York or the Arc de Triomphe to Paris.

Being in contact with high officialdom meant that my grandfather had to adjust his work hours to sync with Stalin’s nocturnal schedule. He frequently traveled to Moscow to meet with various sleep-deprived others – architects, builders, managers, party officials – who trembled before the tyrant’s whim. When in town on ceramic tile business, he stayed with relatives. Once he was hosted by Ziama, who had recently returned from New York. That night the two of them sat at the kitchen table, drank strong tea and talked into the small hours about America.

Ziama’s veneer of cool nonchalance was often broken by barely contained ebullience: “They are unimaginably rich – they leave cigarette butts five centimeters long!” he would exclaim, indicating the distance with his thumb and forefinger, his own cigarette dangling from his lip, eyes squinting against the curling smoke. My grandfather was by nature a cautious man, but with a mischievous contrarian streak, so he took a skeptical view of this and similar barely-believable assertions. “What about the slums and tenements we read about, where the oppressed laboring masses live?” he asked. Ziama took a long drag of his cigarette, burning it down to his fingertips. “Yes, there are slums. I have seen these slums. Your party bosses in Kharkov should be glad to live in such slums.”

About a week after returning home my grandfather was urgently summoned to the office of the plant’s senior party boss: he was to take the midnight express to Moscow and, upon arrival, to report directly to the central headquarters of the organs of state security located on Dzerzhinsky (formerly Lubyanka) Square. As it was already late evening, he had no time to return home to say goodbye to his family, but he was assured, ambiguously, that there was no need to pack for this particular trip.

Grandfather did as he was told, and the next morning, knees buckling under the gaze of Iron Felix, presented himself at MGB headquarters. A uniformed officer with cornflower blue stripes on his shoulder boards led him through a maze of long, red-carpeted corridors to a windowless room. After a long, nerve-shattering wait, he was interviewed at length about his uncle: friends, acquaintances, personal habits, political views, literary and artistic interests, wartime activities, foreign contacts, connections with Zionist organizations, etc. At the conclusion of the interview, he was presented a typewritten transcript recording verbatim their late-night conversation concerning American cigarette butts, slums and allied topics, as well as his own mulish refusal to take his uncle’s stories at face value. He was invited to study this document and, if satisfied that it reflected reality, to sign a statement to that effect. This he did, whereupon he was free to go, saved by his own pigheadedness.

Ziama was already under arrest. He spent seven years in the camps and returned home after the institution of Khrushchev’s reforms – rehabilitated as a victim of Stalin’s excesses, but crippled, his physical capacity to grovel before the West seriously diminished.

Jazz

After Stalin’s death in 1953 the danger receded somewhat. At ten, dad began to study English with a courtly, elderly matron from the old Baltic German aristocracy who, unfortunately, had never met a living Englishman or American in her life. He devoured books by O. Henry, Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck and John Dos Passos – writers whom the regime considered ideologically simpatico, and who were therefore widely available in both English and Russian.

But the true school of America was her music, which dad discovered listening to a tinny Telefunken radio that had been liberated from the Germans, on a program called the Voice of America Jazz Hour, broadcast nightly on shortwave and hosted by a man named Willis Conover. Conover is practically unknown to most Americans, but he ranks with Alexander Solzhenitsyn, John Paul II, Ronald Reagan and Maggie Thatcher in Eastern Europe’s pantheon of freedom. His program began with the opening bars of Duke Ellington’s and Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train”, over which his smoky baritone announced, “This is Music USA, from the Voice of America”. There followed an hour of jazz greats: Basie, Louis, Ella, Billie, Dizzy, Benny Goodman, Oscar Peterson, Stan Kenton, Art Tatum, expertly curated and narrated by Conover from his Washington, DC studio in clear, measured American English. The program was completely free from news and politics. And yet, to millions across Eastern Europe, the music itself was the message: it was the sound and soul of freedom. I remember when, on one of our first visits to New York, dad asked for directions and was told he had to “take the A train” uptown – it was as though he had received an electric shock.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of VOA in general, and Conover in particular, in shaping America’s image in the minds of the Soviet liberal intelligentsia. It might make an interesting study to fix the precise number of armored divisions in the Fulda Gap replaced by Willis Conover and his LP collection. Perhaps the KGB had done the analysis, as Conover was frequently jammed. In strict return-on-investment terms, it was perhaps the best foreign policy money the United States ever spent.

Somewhere dad obtained a glossy brochure extolling “the wonderful family of Ford automobiles for the 1959 model year” from the American Trade and Cultural Fair, held that summer in Moscow – the venue for the famous impromptu “kitchen debate” between Nixon and Khrushchev. Its pages were filled with enormous, gleaming Galaxies, Thunderbirds, Fairlanes, Skyliners and Country Squires – “the world’s most beautifully proportioned cars,” according to the brochure, and dad saw no reason to argue. For years that brochure inspired recurring daydreams like this one, recorded in a book dad wrote many years later:

“The sun shines brightly. The road is wide and straight as an arrow. I am behind the wheel, reclining casually in the broad seat. Jazz is softly playing on the radio. I’m in no hurry. I stop at a gas station, refresh myself with Coca-Cola and drive, drive… I am driving in America!”

Welcome to the United States

In the summer of 1978 mom, dad and I arrived in the United States. When first, dazed and tired, we stepped off the Alitalia 747 and into the JFK international arrivals area, two important things happened. First, dad approached the most official looking person within visual range, explained who we were and asked where we needed to go. The official-looking person understood, responded cheerfully, finishing with the words, “Welcome to the United States.” Dad understood every word, and at that moment he knew that our little lifeboat had landed on a safe and friendly shore. He was instantly at home. (It must be said that dad tried the same trick again the following day when we landed in Houston. He could still make himself understood, but the response, drawled out in Texan, caused much consternation and self-doubt.)

It turned out that where we needed to go was a kind of steel cage holding pen somewhere in the bowels of JFK, where the teeming refuse of the world’s wretched shores awaited processing by U.S. immigration authorities. This cage was the setting for the second important event of that day. The cage contained a vending machine, and I must have found myself staring at it, more from dazed exhaustion than in wonder at the bounty within. A very large black airport worker approached, produced a coin from the pocket of his overalls, deposited it in the machine and pulled the knob. The machine emitted a box of Junior Mints, which the man silently handed to my eight year old self. Then, without a word, he walked away.

Later, in the heat of the Texas summer, the Junior Mints melted all over the inside of my mother’s purse, but the effect on the three of us of this small act of welcome was unforgettable.

Promised Land

The United States had been a constant presence in my father’s imagination for decades, and he was, in theory, well informed about the place. His discovery of America therefore put flesh on familiar concepts and mental images.

Still, the first years were full of surprises. At first he was mystified by the staggering naiveté of many Americans. One common question was particularly baffling: “Why did you leave the Soviet Union?” One would have thought that the question answered itself: the squalor; the antisemitism; the ubiquitous corruption; the soul-crushing quotidian grind of scratching out a minimally tolerable standard of living; the reflexive hushed tones and constant looking over one’s shoulder; an intellectual life lived furtively in half-darkness and strewn with hidden pitfalls and land mines; the utter lack of prospect of a future filled with anything but more of the same. Most of all, the oppressive, all-pervading falseness, and the requirement, strictly enforced, to pay tribute to monstrous lies.

But in most cases the ignorance was good-natured. Most Americans went about their lives seemingly unencumbered by ideology and the struggle against global communism occupied a tiny corner in the attic of their minds. In addition, for many people, their natural distrust of government worked to discount the official line on the evils of communism. This is what living in a free country was like: going about your life, as oblivious to your freedom as a fish to water.

After explaining why he left the Soviet Union a few dozen or a few hundred times, dad developed two standard responses: 1) “Because I wanted to listen to more jazz”; and 2) “Because I don’t like vodka.” This was easier than answering with an earnest litany of reasons.

Still, the Cold War provided a certain clarity and structure to the national purpose. When it ended with the miraculous events of 1989, that structure evaporated and, after a brief and fairly sober moment of triumph, the country’s psyche began to drift and slide. Far from signaling the end of ideology, the Soviet Union’s collapse greatly expanded the ideological range of acceptable political opinion and opened up new territory where it would have been unthinkable to venture a generation earlier. Paradoxically, the end of the life-or-death ideological struggle with communism led to more division and polarization at home, not less.

The last several election cycles before he died in 2013 sent dad into a deep gloom about the country, brought on by the creeping realization of just how intellectually bankrupt were most of the people in charge of its leading institutions. The degree of political unanimity and naked partisanship of the country’s elite astonished and depressed him, as did the viciousness and contempt with which dissenters were vilified and hounded out of polite society. At no time in its history did the country have a ruling class as unified in its worldview, as incestuous in its interrelationships, as homogeneous in its social and educational background, as contemptuous of those supposedly beneath them, as intolerant of dissent, as riddled with conflicts of interest, as narrowly self-interested, as politically and economically powerful, as self-satisfied, as dismissive of the country’s core principles, or as monolithically united behind a single political party. The country increasingly was beginning to resemble a one-party state.

The last several election cycles before he died in 2013 sent dad into a deep gloom about the country, brought on by the creeping realization of just how intellectually bankrupt were most of the people in charge of its leading institutions. The degree of political unanimity and naked partisanship of the country’s elite astonished and depressed him, as did the viciousness and contempt with which dissenters were vilified and hounded out of polite society. At no time in its history did the country have a ruling class as unified in its worldview, as incestuous in its interrelationships, as homogeneous in its social and educational background, as contemptuous of those supposedly beneath them, as intolerant of dissent, as riddled with conflicts of interest, as narrowly self-interested, as politically and economically powerful, as self-satisfied, as dismissive of the country’s core principles, or as monolithically united behind a single political party. The country increasingly was beginning to resemble a one-party state.

Dad dismissed the notion that freedom beats in every human heart – he had come from a place rife with counterexamples to that claim. Rather, he saw American freedom as a highly contingent and fragile cultural artifact, whose threshold condition was a very particular, rare and fleeting set of psychological circumstances and specific habits of mind. This condition belonged to a people, some of whom were still around in 1978, but who, from dad’s later vantage point, seemed increasingly as exotic as Etruscans or Sumerians. Americans were giving up on economic liberty, and political liberty seemed to him to be hanging by a thread. There were also serious doubts about the viability of individual rights in a society whose elites insisted on elevating group rights to preeminence. And the American mind, in thrall to the insane tyranny of political correctness, seemed to be closing on traditional freedoms of speech, conscience and religion. He had always resisted facile comparisons between the two superpowers, believing the United States to be unique in kind, and not just a mirror image of its adversary. But, seeing the world through the lens of his experience, he could not help but see familiar parallels. No, there were as yet no re-education camps, but increasingly, America was becoming a land that required one to pay lip service to untruth.

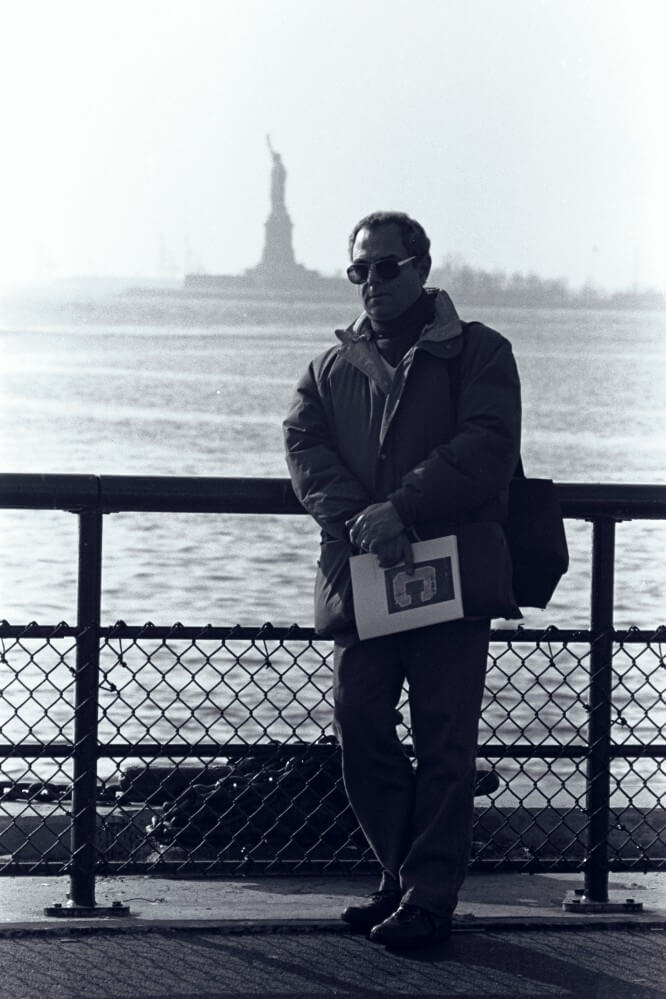

I am sure that dad never stopped loving America. I can’t even say that he felt much disappointment. His feelings were more akin to watching a beloved aunt, once elegant, beautiful and wise, sink into forgetfulness and decrepitude, well on her way to dementia, her robes faded and stained, her brow no longer clear and confident, her torch and diadem securely locked away out of reach for safety reasons, the tabula ansata long ago hocked or misplaced. You don’t stop loving her; you just accept, fatalistically, that this arc of rise and decline is probably in the nature of things.

In 1996 dad and I drove from Chicago to Palo Alto together, just the two of us. This trip took place after dad had already seen much of the United States and a good bit of the rest of the world. But neither of us had ever made this cross-country trip before. He was beside himself with the joy of the journey and the slow unfolding before our eyes of a vast continent of staggering beauty and variety: the broad sweep of the Mississippi along the Wisconsin-Minnesota border; the treeless wilderness of the South Dakota prairie; the gothic spires of the Tetons; the otherworldly landscape of the Badlands; the herds of buffalo roaming the valleys of Yellowstone; the quirky weirdness of the roadside attractions. At times we listened to jazz, pausing more than once to refresh ourselves with Coca-Cola.

Looking back on this trip, I think that, despite his gloom, a flame of hope must have continued to burn. It would be hard to put one’s finger on its source. Perhaps it was the suspicion that a civilization as idiosyncratic and vast as America’s is not easily extinguished, and that the United States is uniquely resilient and capable of renewal and surprise. I also think he shared Churchill’s faith that Americans can always be counted on to do the right thing – after trying everything else.

Published in General

Thank you for a beautifully written story of history and personal history, I plan on re-reading it again.

Wow! Thank you for giving us Americans a glimpse into your family’s journey to the United States and to our slide since the 50s. I’ll have to read this again. There is way too much information for me to gather on just one pass.

Wow. Beautiful and moving.

Thank you so much!!!

Superb! Thanks!

Like.

(All that needs to be said.)

Seawriter

Very moving. A strong case for legal immigration. A reminder of the value of individual freedom…and how easily it might be lost if we forget our Founding Principles. Thank you. May God bless you and your family.

Lovely to read. Your father must have been quite a man.

Brilliant! I want to say so many things but I will just start off by saying that this should go on the Main Feed if it isn’t there already. As to the other things I wish to say I am finding it hard to organize my thoughts as so many memories are rushing to the forefront of my mind.

I will say this though. No one can really appreciate America quite in the same fashion as those who come to its shores seeking refuge. The fact that such people still come to America even to this day I think gives me hope that not all is lost. As decadent and self centered as some of the natives can get America has always been able to refresh her blood with people like your father.

Excellent. Thanks.

By the way, I doubt I have met more than three Russians in Texas in my lifetime. How did your family pick a state to live in?

How can you be in Spring, TX and not have met Russians? There is a Russian Orthodox Church in North Houston (St. Vladmir) and they are putting up a new building near Beltway Eight on the north side.

There are buckets of Russians in the Houston area. The biggest concentration is in the Clear Lake area because of Johnson Space Center, but a lot of Russians who work in oil and gas have relocated here and vastly outnumber the aerospace types.

Seawriter

To echo everyone, this is a great post. Thanks.

Wonderful; thanks Oblomov!

Freedom is addictive. Once people have it, they don’t want to let it go.

I stand corrected. Perhaps there are plenty of Russians nearby, but they must be concentrated enough in particular areas that one doesn’t often meet them beyond.

When people ask where I’m from, I always say “north of Houston” rather than simply “Houston” because I pointedly avoid going into the city if I can help it. The suburb of Spring is more urban than it was twenty years ago, but it is still distinct from Houston proper. St Vladimir’s is apparently close to the 610 loop, where I would only ever venture for a museum, a concert, or a ball game. People who live on the north side (Spring, Tomball, The Woodlands, Conroe) tend to spend most of their time in that general area, best I can tell.

Immigrants tend to favor areas with climates similar to their original country. That’s one reason why Minnesota has so many Swedes and Norwegians while so many Vietnamese settled along the Gulf Coast. If Russians are not too difficult to find down South, I suspect that their populations here pale in comparison to communities up north… where Junior Mints don’t melt even before they are sold.

Superb post – the best and most interesting I have read here. I hope you have the time and the will to keep these sorts of posts going.

Excellent story. One phrase that first caught my eye when your father gave reasons for leaving Russia: “not having to pay lip service to untruths”. Later you state “but increasingly, America was becoming a land that required one to pay lip service to untruth.” We so often

are forced by “political correctness” to acquiesce to untruths rather than be labeled a racist, homophobe, bigot, etc. Those who have lived without freedom cherish most the freedoms we are so willingly giving away.

I say, “Wow,” as well! Thank you, Oblomov. God bless your dad’s memory. This piece made my day.

That’s kind of a funny story. The reason we landed in Houston is that one of my parents’ oldest friends, in fact the guy who introduced the two of them, lived in… …Waco (!) He and his family emigrated two years before we did. I imagine they were the only Russian Jews in town. How they ended up there I don’t know, but the system worked in strange ways. In any case, we left Texas after less than two months.

Thanks for all the positive comments, y’all!

Wonderful.

Thank you.

Very like. Большое спасибо.

What an uplifting article. More please!

Thank you so much.

Much to think upon,

Thank you again, and God bless your Father and Mother – how did they get out of the Soviet Union? What happened to your Uncle?

Enjoyed reading this, thanks for posting

That reminds of the scene at the end of Fiddler on the Roof when the Russian characters are talking about where they will live. “Chicago, America? We are going to New York, America. We will be neighbors!”

12 months from now this will still be the post of the year.

Thank you for sharing your heritage, and reminding us of ours, Oblomov. A wonderful piece of history and writing.

This was beautiful, Oblomov, thank you!

A wonderful story, beautifully told. Thanks for sharing your family history with us.

Was your family’s emigration, Oblomov, a result of liberalized Soviet emigration policies at about the time of the Jackson-Vanik amendment here in the U.S.?

Yes! Precisely. Scoop Jackson and Chuck Vanik are by far my favorite Democrats. In effect, the Jackson-Vanik amendment forced the Sovs to allow Jewish (and other) emigration or face a cutoff of the sale of American grain.

Yes, that is exactly what it was like.

I never met my grandfather’s uncle. I believe he died some time in the early 1960s. His story wasn’t that unusual. At that time there were millions of former Gulag inmates living throughout the Soviet Union. There is a stunning short novel about such people by Vasily Grossman called “Everything Flows”. I highly recommend it and everything by Grossman.