Ricochet is the best place on the internet to discuss the issues of the day, either through commenting on posts or writing your own for our active and dynamic community in a fully moderated environment. In addition, the Ricochet Audio Network offers over 50 original podcasts with new episodes released every day.

Colombians Have Lost Hope in Peace Process

Colombians Have Lost Hope in Peace Process

The chances of a historic peace accord between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Marxist guerilla group with which it has been in a state of armed conflict since 1964, have never looked bleaker since the Havana negotiations commenced in October 2012.

The chances of a historic peace accord between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Marxist guerilla group with which it has been in a state of armed conflict since 1964, have never looked bleaker since the Havana negotiations commenced in October 2012.

As talks continued outside the country, the recent escalation of warfare within it is exhausting a nation that has seen its armed forces, infrastructure, and environment attacked by the FARC on 145 separate occasions since last May. After more than 1,000 days at the negotiating table, Colombians have lost hope in reaching a peace agreement.

In July, in a national televised address to the nation, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos announced that the FARC had again agreed to a unilateral ceasefire. This marked the FARC’s sixth attempt at a truce; they violated the most recent one in April when their guerrillas ambushed a Colombian squadron in Cauca, leaving 10 soldiers dead. Santos also, for the first, time announced orders to “de-escalate” military action by Colombian armed forces for a period of four months, subject to the FARC’s meeting the government’s conditions.

The announcement was greeted with skepticism, most notably by former President and current Senator Álvaro Uribe. Santos’ critics suggested this was a step toward a bilateral ceasefire, a concept they opposed absent the signing of an agreement. Additionally, the four-month period coincided with regional elections. Colombians recall the FARC agreeing to a unilateral ceasefire during the presidential campaign in 2014, only to ramp up attacks after Santos was re-elected. Santos argues, however, that the de-escalation will expedite the peace process, and that he will decide at the end of the term if there is enough movement on outstanding issues to warrant continued discussions.

The negotiations in Havana saw significant achievements, but the most critical issues –- justice, disarmament, and how the agreed points will be implemented — remain unresolved. The issue of justice is now receiving the most attention. According to a June Gallup poll, 85% of Colombians want the FARC’s leaders to serve prison time for their war crimes and their crimes against humanity before they can enter into politics. The FARC’s leaders have made it clear that they do not agree, stating repeatedly that they “will not spend a single day in prison.” Trying to strike a balance between the two has been costly for Santos, who has seen his approval ratings plummet to 25%. The Santos Administration has reiterated that the FARC’s leaders must accept transitional justice (administered by an international court), but it is also open to alternative forms of sentencing outside of a traditional prison cell.

Over the years, the FARC has reconstructed itself from a purely Marxist guerilla outfit into a narco-trafficking terrorist organization. The Medellín-based think tank, Insight Crime, estimates the FARC’s annual drug income to be between $150 million and $500 million, most of which is believed to fund their military efforts. The guerrilla group controls 70% of coca cultivation in the country and is involved in various levels of trafficking, although to what extent is unclear.

A June 2015 UN report revealed that Colombia has increased coca cultivation from 48,000 hectares to 69,000 hectares. Production has almost doubled in the past year, from 290 tons in 2014 to 442 tons now. The report was published a year after the FARC and the Colombian government reached an interim agreement calling for both sides to share the responsibility of eradicating coca and implementing crop-substitution for farmers, among other joint initiatives during the post-conflict period.

The UN report further complicates matters of justice. Negotiators for the FARC have attempted to classify narcotic activities as a political crime, which would ultimately shield those responsible from extradition by US authorities. The report fuels skepticism among Colombians, and raises questions about whether the FARC is serious about implementing the agreed measures to eliminate drug cultivation and trafficking in the post-conflict period.

After 50 years of conflict and multiple failed peace negotiations, it’s difficult to foresee anything but more conflict ahead. Negotiators are to be commended for the progress they’ve made, but the remaining issues are complex, and emotions about them run very deep. In the short term, the most likely outcome is that the FARC will make some concessions, perhaps in terms of reparations for victims. Both sides are reported to be nearing agreement on such a plan. This will probably give the Colombian government an incentive to make another pitch to the nation for extending the talks. Yet little progress will be made on justice and disarmament. As some analysts have said, describing the FARC, “Nobody negotiates a peace agreement only to serve prison time thereafter.”

There are probably three mid-term scenarios:

- Santos, aware he doesn’t have time on his side, goes to the nation with a referendum on a peace agreement that fails to ensure prison time for the FARC leaders;

- The Santos administration goes it alone and agrees to a special constitutional assembly, ratifying a flawed deal and bypassing a public referendum; or

- Talks fall apart and the conflict continues.

Opinion polls conducted now suggest the country will reject any agreement that does not guarantee prison time for the FARC’s leaders.

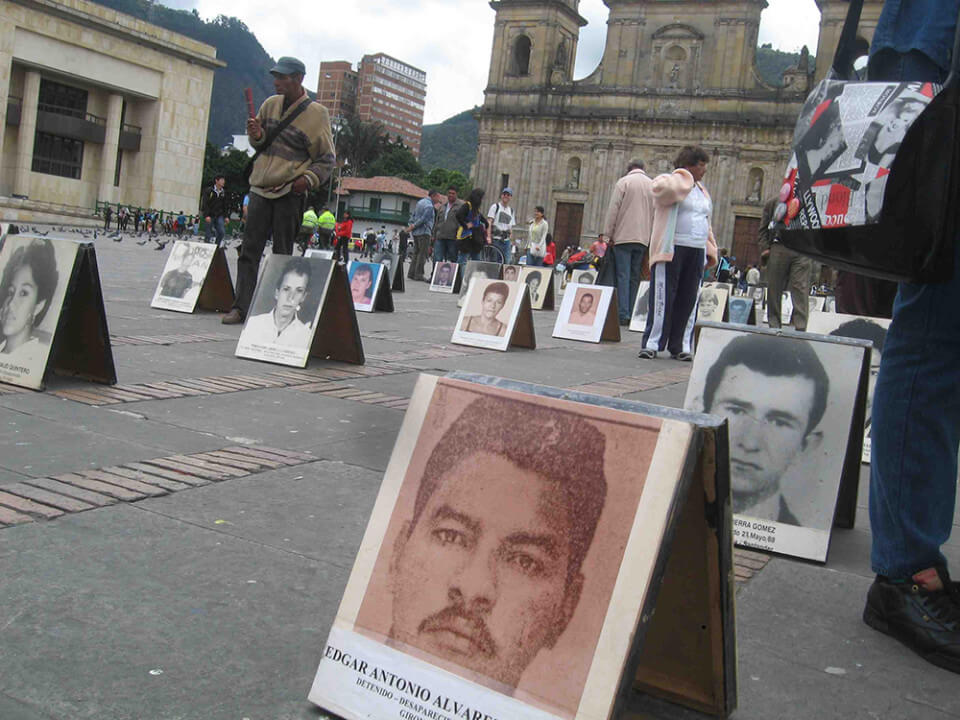

Aside from the uncertain constitutional legitimacy of the second scenario, foregoing a referendum would result in the exclusion of the voice of a nation that has seen more than 220,000 deaths and five million people displaced as a result of this conflict. With his approval rating hovering in the mid-20s, it’s difficult to imagine Santos going down this path.

That leaves us with the third scenario. Unless the FARC’s leaders capitulate at the negotiating table, a prospect no one is counting on, the talks will eventually halt, and the conflict will carry on.

Given last year’s increases in coca cultivation and production, the FARC may be preparing for exactly that.

Published in Foreign Policy, General

Wow. I was totally unaware of this. Thanks for bringing it up.

I can’t imagine how this standoff could end without some justice for the victims. It’s frightening to think that FARC will get away with this.

I was under the impression that during the Bush years, significant progress had been made in degrading FARC. Was that true? Was the progress real, or superficial? If it was real, what has caused the reversal?

I think a point to be stressed for American readers is that we’ve been a big player in this story. I’d like to hear Scott’s thoughts about whether our efforts have on the whole been helpful or worth it. It does not sound so, from this bleak account — one which correlates with what I hear elsewhere.

FARC needs executing, not short prison terms. Has the region not learned the lessons of Hugo Chavez?

Usually, getting away with it is what happens in transitional justice. At its best, it seems to mean, transitioning to a future where there is some justice. Perhaps the ugly truth is that the end of civil war is a greater good than justice. Pity the people living in such countries that they have to decide on these matters.

The FARC was largely destroyed by Uribe, with Santos as Minister of Defense, that is one of the reasons so much of the narcotics business moved to Central America and Mexico. The peace negotiation was an attempt by the Cubans to legitimize the FARC and bring it into the political process. The Cuban security apparatus abandoned military struggle and chose an electoral strategy after their efforts in Central America collapsed along with the Soviet Union. Chavez’ second win followed by wins in Bolivia and Ecuador rewarded their efforts, but Correa hasn’t paned out for them. Their effort in Peru failed and Colombia was never an option, at least not in the short and medium term. Still the FARC has made gains on the ground and in recouping their narcotics business to some extent with Venezuelan help but hasn’t shown a great deal of interest in abandoning the armed struggle. because that is what they do. They are a violent sub culture that has been murdering, kidnapping and making millions for many decades and several generations. They wouldn’t survive in Colombian politics the way M -19 members have as the latter were upper or middle class educated leftists. Ideology for the FARC is just PR for witless westerners and a unifying myth for young thugs. The Colombians know better. The peace process isn’t a process of peace and it won’t end the FARC’s violence, but it may win reprieve for some who want out.

I think on the whole there is no doubt that American efforts have helped Colombia. Farc boasted more than 20,000 members in 2000; it’s reported that there are now approximately 6,000 members. Much of the US efforts are attributed to military training and equipment by US along with intelligence coordination. That said, Plan Colombia is controversial here. There were many military successes, but there were also claims of abuses of power committed by ex US military personnel (acting essentially as mercenaries) including sexual assault of women. The early 2015 report of DEA agents with prostitutes at parties paid by organized crime bosses strikes that chord again. The drug problem remains and I think there needs to be a bigger conversation with more focus on addiction in drug consuming nations. But as a whole, Colombia has made great strides and the fact that a peace process exists is a testament to those joint efforts.

What’s most striking to me is the similarities between President Santos of Colombia with his peace process and the Iran talks with President Obama. Both presidents have staked their political legacies on striking a deal. Both want a deal more than the other side. Both are giving the benefit of the doubt to terrorist regimes (Farc and Iran). Both have made unwarranted concessions. Both deals are highly unpopular with their respective electorate. Both are ultimately putting their political interests in front of national security interest in my humble opinion.

How unified is the FARC — do they have a clear chain of command? Are those who are negotiating on their behalf seen as legitimate by the rank-and-file? Are they able to keep discipline over all their factions?

By the way, for those who wonder why I gasp when people casually tell me we should take the PKK off the terror list … FARC, PKK, same kind of thing. Marxist-Leninist (or Maoist, more properly) in origin, originally funded by the Soviets, beloved by witless westerners, financed through narcotics and human trafficking. It’s like we’ve suddenly announced FARC is our new ally against ISIS.

Of course, yes, FARC probably would be pretty good at fighting ISIS — they’ve got lots of experience with this kind of fighting — but Colombians might understandably be taken about by this policy change. Anyway, I digress.

It wasn’t the US so much as President Uribe. He worked with us, but he was taking a realistic view of FARC: he was actually fighting them. He recognized the enemy for what it was.

Unfortunately he was term-limited due to the Colombian constitution, and Santos hasn’t turned out to be the replacement the Colombians were hoping for, that is, a continuation of Uribe.

Given the choices above, option 3 is probably best, unfortunately. There’s only one solution to FARC, and it doesn’t involve coexistence.

(My wife was born in Colombia. Her father tells stories of having to sleep in the jungle so they wouldn’t be butchered in their beds by the FARC.)

Scott I don’t believe the 20,000 figure for 2000, or at least it’s meaningfulness. The FARC was on the run, being successfully chased down and killed or captured. Many were surrendering, happy to get out of the jungle and into jail. Our intelligence and communications were critical to their success, so were Pastrana’s hapless efforts to negotiate with the FARC. Even the naive human rights groups and Europeans finally came to see these people for what they were. The FARC were also basically finished in the mid seventies as well. Remember we were worried about the M19, ANAPO, and the ELN. Then we defeated the cocaine paste trade from Bolivia and the cocaine growing moved to the Colombian hinterland, made alliances with the FARC and local peasants and the FARC surged forward. There were abuses, there always are, but highly exaggerated, at least to the extent blamed on the Colombian military. The Colombian military were and are the most professional military in South America and Colombians from all classes are required to serve and actually do. The police in contrast were rotten at all levels and had been before drugs made it all much worse. The paramilitaries formed during this period, at first as vigilantes and popular, going after FARC kidnappers; they defended the ranchers and farmers where the government couldn’t or wouldn’t. Then the paras got into the business themselves. The peasants. small towns and villages got caught between the two groups. Ugly.

Exactly. And you continue to see this reflected in approval polls:

Uribe = 55% approval (despite gov’t pursuit of uribistas on alleged charges of abuse of gov’t power while in office – that’s a post for another time)

Santos = 29%

John, I agree with you 100%. Just pointing out some of the criticism from folks here on abuses. And if this deal goes through as is, I think you will see more organized crime groups come on the scene as we saw with the ex-paramilitaries (urabeños, etc). Collusion between farc and those groups is occurring now.

That is exactly the problem.

Scott, I was disturbed that Obama named Aronson as liaison I’m not up on what is happening and what role we are trying to play. What role is he playing?

How much of this is directly related to Santos’ handling of the negotiations? What percentage of the population sees this as the key issue? How much of the disapproval is related to a general sense of public security worsening, corruption worsening, prices rising? Is there a big division of opinion between urban and rural areas?

How does the military view the negotiations?

Not really sure, John, but if Farc leader Simon Trinidad is eventually released from US prison to join negotiations in Havana then we’ll know why Aronson was brought into process. Farc has repeatedly made this request. US denies that he’s in play but as WaPo points out, Obama now has set precedent.

Claire, great questions. Tough to answer. I think they generally have a clear chain of command. However, the April ambush by Farc raises questions. Additionally, the coke biz plays a huge role. The southern bloc of Farc, who controls a large chunk of Farc’s coca crop, was not initially represented in Havana. They eventually joined negotiations but it raised suspicions. I think it no matter what is signed, you are going to have some farc members not comply and continue on with their narco activities.

Scott. All the FARC needs from us is pressure for a cease fire, especially after the FARC breaks a cease fire or expands without push back. I figured this would be Aronson’s role, because he would sincerely believe cease fires would work in the direction of peace. He’s wrong, or at least it hasn’t in the past and I can’t think of a reason it should. When the Colombians say they want them in jail I think it means they want the Colombian military to continue to kill and capture them and use the peace talks to arrange for their surrender. The Cubans are running this process and they are patient and know how to play the media especially liberal media in the US. Aronson is sensitive to media pressure. I suppose it’s in Colombia’s interest that nobody in this country is paying attention.

Would legalizing drugs help?

I know that this is a huge question and I don’t want to derail learning about Uribe and Farc, but if the U.S. legalized cocaine then wouldn’t FARC still be able to sell American drug users cocaine? Is there any reason to believe that it would be dramatically cheaper from the elected Columbian government?

I ask because I don’t know too much about the drug trade.

One expects it would lower the profits and reduce money flow to FARC.

Of course, but what is the likelihood of that? Just switching from supply side efforts to demand reduction would do a lot. Indeed, I’d say posing the question between continuing our insane war on drugs and legalization is like Obama saying it’s the Iran deal or war. Actually there are few things dumber than continuing current policy of erecting non tariff barriers that assure robust domestic profits. The other dumb thing would be to keep the war on drugs but decriminalize the domestic trade, i.e. increase demand by reducing costs but keep the non tariff barriers in place.